Early in the shelter-in-place process to prevent spread of COVID-19, newspapers, researchers, and public agencies began publishing data showing heavily disproportionate numbers of positive coronavirus tests and deaths in predominantly Black, Latino, and low-income neighborhoods. The virus seemed to be charting a taxonomy of social and economic disparity: unequal access to healthcare, service workers laboring under unsafe conditions, and a public transportation system—otherwise considered a great social leveler—rendered a nexus for the spread of disease. By May 1, it was reported, more than 3,000 Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) workers had tested positive, and 98 had perished.

Demographic studies have commonly indicated a correlation between poverty, spread of COVID-19, and serious complications from the infection in New York City. The New School’s Urban Systems Lab used census and NY Department of Health data to map concentrations of cases alongside indicators of social vulnerability and projected climate impacts. Low-income neighborhoods and communities of color are consistently the most adversely affected, with the worst impacts correlating with lack of health insurance, high-density inhabitation of residential units, and higher numbers of elderly residents.

As information accumulates about the spread of coronavirus, transit agencies, researchers, engineers, and architects are wrestling with its implications for the design of public transit systems and the future of cities. How can networks be adapted to meet public safety guidelines of six feet of separation between people? What long-term changes in paradigms, infrastructures, technology, materials, maintenance, and behavioral habits will the crisis provoke and necessitate? What policy shifts can make whole the previously thankless labor of grocery clerks, stock boys, warehouse employees, food processors, nurses, doctors, EMTs, pharmacists, truckers, and sanitation and maintenance people christened “essential workers”?

For firms working in the public transportation sector like Dattner Architects, Gensler, and Nelson\Nygard, and policy advocates at Transportation Alternatives, greater emphasis on maintenance and cleanliness, incorporating new materials, improvements in service, better distribution of transportation funding, and reimagining the city’s planning and public spaces could be critical outcomes. “Some things are definitely going to affect us a long time,” says David Epstein, a Gensler design director and principal specializing in the future of cities. “Architecture’s basic core premise is about security and shelter. In these times, you’re looking for anything that makes society feel safer. The environments that we create will be at the front of the mind right now. How do we create environments that the public feels safe in? That’s going to touch many aspects.”

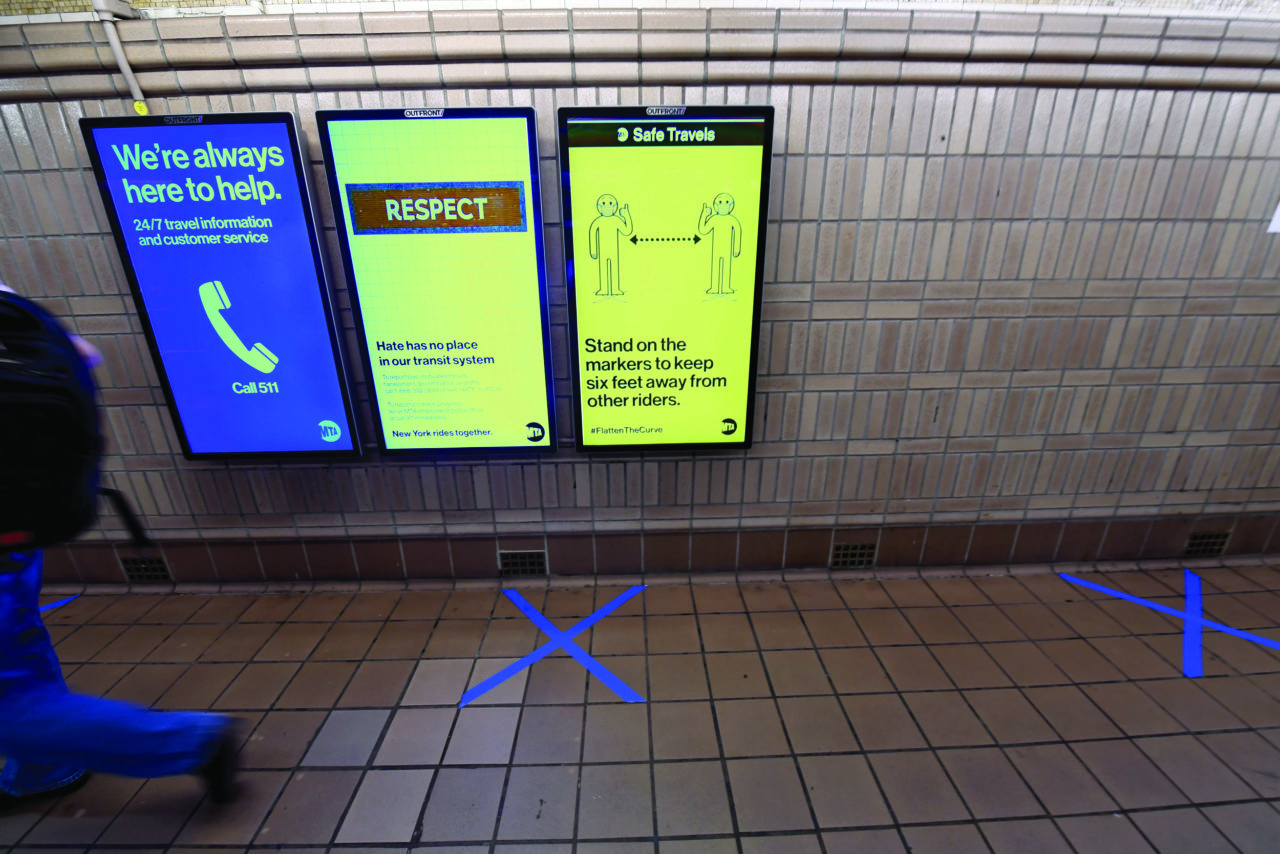

Epstein mentions emerging practices like taping sidewalks and public spaces at six-foot intervals to mark safe distances of separation, and the absorption of the street by café and restaurant seating as examples of how the public is quickly adapting, reshaping cities and transportation systems. A study released in April by MIT economist Jeffrey Harris, “The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City,” has been widely criticized for its methodology, but still set off questions about the subway’s role in the outbreak and pointed at vast disparities in usage between boroughs. Before the virus, open gangway subway cars were already ordered to allow for more space; now they might contribute to providing greater distance between passengers. In late March, the MTA asked riders to avoid public transit to allow essential workers safer passage. As parts of the economy reopen, it may encourage those living closer to their jobs to walk or use an alternative form of transportation, which could reshape land use and planning decisions toward a more walkable city where people live closer to work. “I could see returning to almost a village mentality,” Epstein says. “Making walkable villages would be spectacular if it came out of this, but that has been in our minds for the last 100 years—making cities more compact.”

In office buildings, Epstein points out, Destination Dispatch elevator systems are being completely overhauled: instead of figuring out how to get the most people to floors efficiently, designers are reprogramming elevators to limit occupancy. In lieu of consolidating in one central location, will corporate headquarters move to a distributed model where people can live closer to work? “There are a lot of conversations happening right now about what the current situation of working from home means,” says Urban Systems Lab fellow Pablo Herreros. “If they were reinterpreted in the new normality we’re going to have to live, perhaps they could also add potentially positive things.”

Larry Gould, a principal of the transportation planning firm Nelson\Nygaard and a former MTA employee, notes that normally the transit system should be flexible enough to change service in response to new conditions. In designing systems, he conducts studies to determine demand, then crafts the service, planning pathways, the number of cars on trains, hours of operation, and intermodal connections. Under normal circumstances, conductors can be redirected before their shifts to busier lines based on changing needs: the MTA is now increasing service in the Bronx, for instance, where the highest demand is being experienced. Despite a massive 90% decrease in ridership, shorthanded staffing reduced their ability to respond to the crisis more quickly, resulting in the alarming instances of crowded cars.

Gould talks about the enormous shift in thinking a six-foot distance represents in a system that had assumed each passenger should have only a three-foot-square area to themselves. In the short term, service can be improved to ensure trains and buses are evenly spaced and loaded, and sneeze barriers and ventilation can be installed to prevent spread of airborne diseases, as the MTA is already doing in its back-of-house areas. Long-term, new materials are undoubtedly being contemplated to help with maintenance and prevent the spread. “The surfaces used inside vehicles and stations were designed generally for reasons other than preventing virus transmission,” Gould says. “They were designed first to be easy and cheap to maintain, to look pretty good even when they’re dirty, to be quick to clean, to be aesthetic for people riding the vehicles and in stations, and in some cases to respect history, particularly in the older parts of the subway. So everything about surfaces in the subways and buses answers to reasons primarily other than virus transmission. I’ve got to believe that in transit agencies all over the world, the people responsible for maintenance are meeting with the people responsible for safety and trying to see where they can change surfaces to maintain them better—surfaces that lend themselves to it.”

The MTA, for its part, has responded to the pandemic with an array of measures. From March 2, when the first cases appeared in New York City, through the end of April, the MTA says it distributed six million gloves and one million masks, cleaned 700 subway and rail stations twice a day, and cleaned the entire fleet of vehicles once every 72 hours. Messaging on screens and at entrances are accompanied by public service announcements giving health and safety guidance. Person-to-person transactions at booths have been eliminated. Plexiglass shields are installed in MTA offices to protect employees, and vinyl shields are being tested for buses. Temperature checks are conducted daily on more than 3,500 employees. Buses began boarding from the rear doors; the front seats are blocked off on express lines to protect drivers. Most recently, the MTA shut down overnight train service from 1am to 5am for cleaning and disinfection, and is testing antimicrobial and ultraviolet treatments. The new Essential Plan Night Service increases bus service by 76% and adds for-hire cars originally contracted for Access-A-Ride to meet riders’ needs.

An article that has aged particularly well amid the pandemic, “Hail the Maintainers,” by Andrew Russell and Lee Vinsel, was written four years ago for the digital magazine Aeon, arguing that maintenance matters more than innovation in most people’s lives. With the desire for better upkeep of systems and appreciation for the role of caregivers and maintenance workers, Dattner Architects Principal Jeff Dugan hopes for a greater value placed on what happens after things are built. Dugan co-chairs AIA New York’s Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, advocating for architectural design in the sector, and is developing an Infrastructure and Crisis program responding to current events. “There’s not enough leadership behind maintenance,” says Dugan, who has designed several MTA stations, including the Hudson Yards 7 train extension. “It’s not just the effort to do it, it’s also the respect for what it means to do it. As architects, of course, we like to design buildings and public spaces. I like to equate it to a house: once it’s built, it starts to deteriorate, it starts to change, and you have to do things to it. Once you build them, you have to maintain them. Cleanliness is one of those things. It’s a two-way street. There are the people who maintain the stations and the cars, and there are the people who use them. If you don’t maintain them, people begin to disrespect the stations.”

For its part, the Urban System Lab is focused on the issue of equity in the pandemic response, aiming to provide open- source applied research to administrators free of cost, using computational resources similar to those developed by private companies like InfoWorks ICM as proprietary software. “Part of the work we’re doing in the lab is to democratize access to that data and say, ‘Here’s another way of doing it,’” says Urban Systems Lab Assistant Director Christopher Kennedy. “More generally, we’re advocating to use more data-driven strategies to target emergency responses to communities that need it the most. We’re not necessarily seeing that in real time. We often work with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency in helping provide the data and tools they might need in addition to what they already have access to and say, ‘South Bronx and Queens actually need additional resources, and that should be a part of any emergency plan that’s put into place.’”

Yet transportation advocates point out that an underlying factor is the lack of funding. Before the crisis, the MTA already suffered a $9.8 billion shortfall for its capital plan. With the loss of ridership, decreases in tax contributions, and mounting costs of the emergency response, the MTA now estimates $125 million a day in lost revenues. Danny Harris, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, joined a group of organizations advocating for $3.8 billion in Congress’s COVID-19 stimulus package to cover the MTA’s operating losses. They are asking for an additional $3.9 billion to cover costs, without any structural improvements.

“I can imagine no shortage of scenarios,” says Harris of the hopes for a change in priorities. “The reality is that we have this administration and any administration that would come next. We should wish to have a high-speed rail network like Japan, Germany, Switzerland, or France, and a bike network like the Netherlands or Denmark. We should wish to have active and vibrant public space as they do throughout southern Europe. But all that requires the political will and the vision that those things are not whimsy, they’re not partisan. When you build them, they create more vibrant and connected regional economies.”

Harris cites a Harvard study that shows the decrease in highway traffic during the COVID-19 crisis has improved health conditions in places like the Bronx, and traces a relationship between the higher rate of virus hospitalizations and deaths with the concentration of diesel-fueled trucks passing through the borough. Transportation Alternatives argues for congestion pricing, lower speed limits, Vision Zero as national policy, and a shift in funding and regulations on the part of the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration away from supporting car travel and in favor of protecting pedestrians and cyclists and improving public transit. “We’re not trying to sell America new ideas,” he says of the organization’s public transportation, walking, and biking advocacy. “We’re trying to encourage them to adopt ones that have been successful in other places for decades.”

The takeaways from the COVID-19 debacle go to the heart of how we choose to live, with the potential to impact public policy and behavior for generations. “If you look at history, cities have survived pandemics, epidemics, flus, plagues—all kinds of things,” Dugan says. “You could probably come up with civilizations that have been eliminated by plagues. The time certainly presents itself as an opportunity for cultural change.”

Stephen Zacks (“Public Transportation in Crisis”) is an architecture critic, urbanist, and curator based in New York City. He is founder and creative director of Flint Public Art Project, co-founder of Chance Ecologies and Nuit Blanche New York, and president of the non-profit Amplifier Inc., which develops art and design programs in underserved cities.