- Introduction

- +Essays

- Editor's Note

- Zoning as Design

- Towards A City of Cities

- The Future of the Zoning Resolution

- Zoning and Design Visualization

- Working with the City

- A Revolutionary Approach to Zoning

- Zoning the Next 100 Years… Or At Least 50

- Vision and Legitimacy: The Planning Basis of Zoning

- Happy 100th Birthday, NYC Zoning Resolution!

- Reflections on the 100th Anniversary of the NYC Zoning Resolution

- Regulating the Good You Can't Think Of

- Zoning for the 21st Century Metropolis

- The Zoning Resolution: A Work in Progress

- Zoning for Tomorrow

- Zoning and Design: It’s Complicated

- What’s Old Is New

- Zoning – The First 100 Years

- One Hundred Years of Zoning

- 100 Years of Zoning

- Authors

- Related Links

- Events

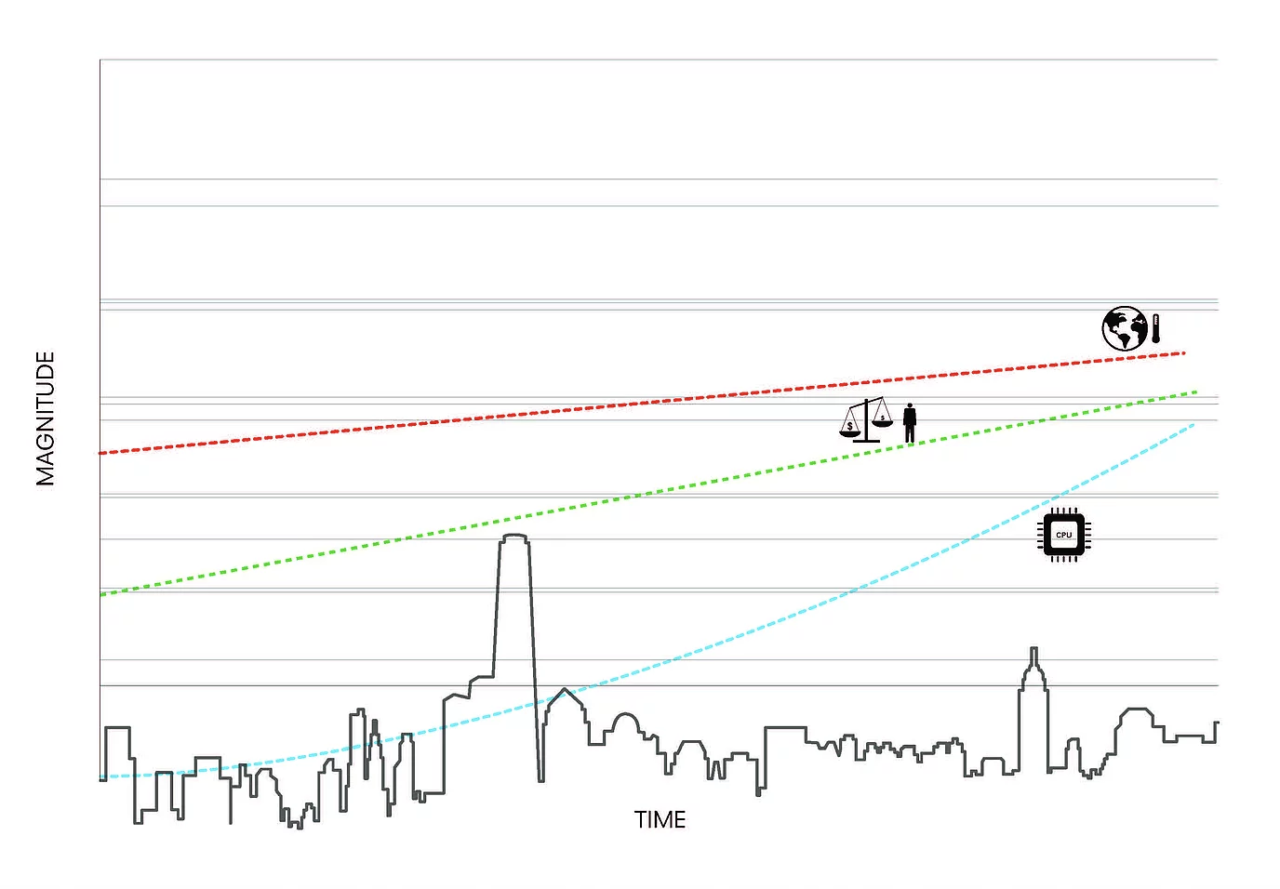

Like internal combustion engines, shopping malls, and hairspray, zoning is a quintessentially twentieth century idea. Born out of the desire not only to encourage light and air to the street, but to segregate uses, dictate form, and regulate density, New York’s century old zoning resolution is firmly out of step with the challenges of our era. Mies van der Rohe famously asked that architecture be of our epoch, which arguably today is defined by three big trends that are increasing geometrically in magnitude: climate change, economic inequity, and technological processing power. Each of these trends is having a profound impact on the geography of our city, an impact that renders much of our existing zoning code obsolete.

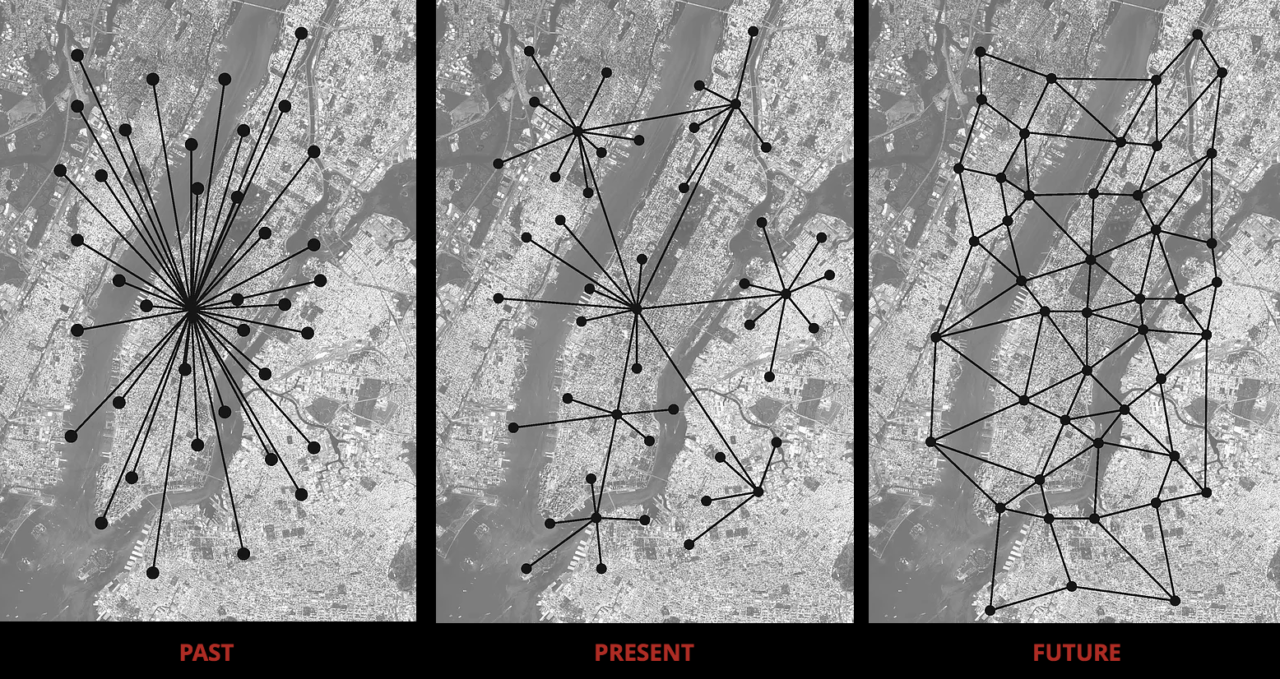

Waning are the days of Mad Men Manhattan in which we all need to commute into a central business district; technology has led us to a multi-nodal city in which living and production happen cheek by jowl. Consider the Flatiron, DUMBO, the Meatpacking District, Domino, Long Island City, Brooklyn Navy Yard, Hudson Yards, and Cornell Tech as just a few examples of the manner in which the territory of our city is moving from a hub-and-spoke city to a networked city. This has profound potential for our city to be more ecological (walking and biking to work), more equitable (evenly distributed commutes with jobs moving to more affordable neighborhoods) and more technological (start ups in pre-war buildings such as Google’s tenancy of 111 Eighth Avenue).

Our big three challenges argue for a common need to heavily desegregate allowed land uses such that where one works, lives, learns, eats, shops, recreates, and experiences culture can all be more proximate. This argues for a zoning code that would encourage the performance characteristics of a more compact “city of cities”, essentially a city moving towards a future of connected high-tech villages, each sustainable for most of our daily needs, but ever stronger for shared physical and cultural bonds with the greater whole.

So what would a revised code that encourages such a city look like?

First, beyond simply promoting density near transit, zoning should encourage programmatic self-sufficiency at most transit nodes, so most of what people need in their daily lives would be accessible by biking, walking, or short transit trips.

Second, our zoning should encourage development to mitigate climate change risk by building away from flood zones when possible, and porous surfaces and defensive building techniques when not. PlaNYC and OneNYC suggest much of this and more, and their recommendations need not be repeated here.

Third, in terms of economic inequity and social mobility, our zoning should obviously encourage affordable housing as the current administration is pursuing, but it should also encourage affordable spaces of production by granting zoning bonuses to office space in the outer boroughs, again near mass transit. Tax policies should be adopted to upgrade our older warehouses and other pre-war buildings to provide the broadband, mechanical equipment, and services that our burgeoning tech economy requires.

Fourth, as many have argued, our zoning should be performance based rather than prescriptive, laying out clear goals for designers and builders to meet so what we need to achieve is emphasized over how we achieve it.

Fifth, we should consider the potential to combine our zoning and building codes into one simple, transparent, and web based new CODE that would govern land use, light and air, health and safety, and all other metrics that impact our city’s built environment.

And finally, there are important things that such a CODE should not do. It should not attempt to regulate architectural expression. We must separate objective debates about scale from subjective debates about aesthetics, accepting that in any great city, like any great museum, we must take the good with the bad. The CODE should not encourage thousands of pages of bureaucratic documents, such as our current environmental impact reports. And finally the CODE should not be labyrinthine; it should be lean, green and clean.

Getting to a new CODE that helps us a build a City of Cities will not be easy. Such an effort could easily consume the activities of an entire City Planning Chair’s tenure, and even then could fall prey to the many special interests who thrive off of the status quo. As an effort it would be the herculean local equivalent of passing gun control legislation or immigration reform, enormous undertakings to be sure, but do we really think such efforts are not worth it? Given the challenges before us, can we afford not to change?

Vishaan Chakrabarti is the founder of Partnership for Architecture & Urbanism and Associate Professor of Practice at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation of Columbia University.