If anyone is perversely waiting for Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) to stumble, after its remarkable string of prominent projects—the High Line, Lincoln Center, the Vagelos Education Center, and The Shed, just to name some local ones—they’ll have to keep waiting. The firm’s long-anticipated renovation of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), collaborating with Gensler, matches strategies to the museum’s evolving program, enhancing the experience for a widening range of visitors and strengthening DS+R’s position as the city’s go-to firm for cultural infrastructure.

This is the fifth physical iteration of an institution that initially embodied modernism as an upstart movement, yet now represents its mainstream: alternately respected and resented, subjected to critiques of corporatization and hegemony. MoMA is both a pantheon and a commercial enterprise, and it must manage the implicit tension between the two. Rem Koolhaas landed a punchline in 1997 with “MoMA, Inc.,” and when Banksy broadsided the entire contemporary art establishment with Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010), though he didn’t single out MoMA for zingers, it was hard not to recall the gift shop/bookstore as a prominent path into or out of MoMA’s 2004 building by Yoshio Taniguchi. With the MoMA Design Store right across 53rd Street, the commercial aspect of the whole campus is inescapable—yet the newly expanded flagship submerges the retail space below grade. Visitors now enter or exit above the gift shop. It’s still visible but no longer central.

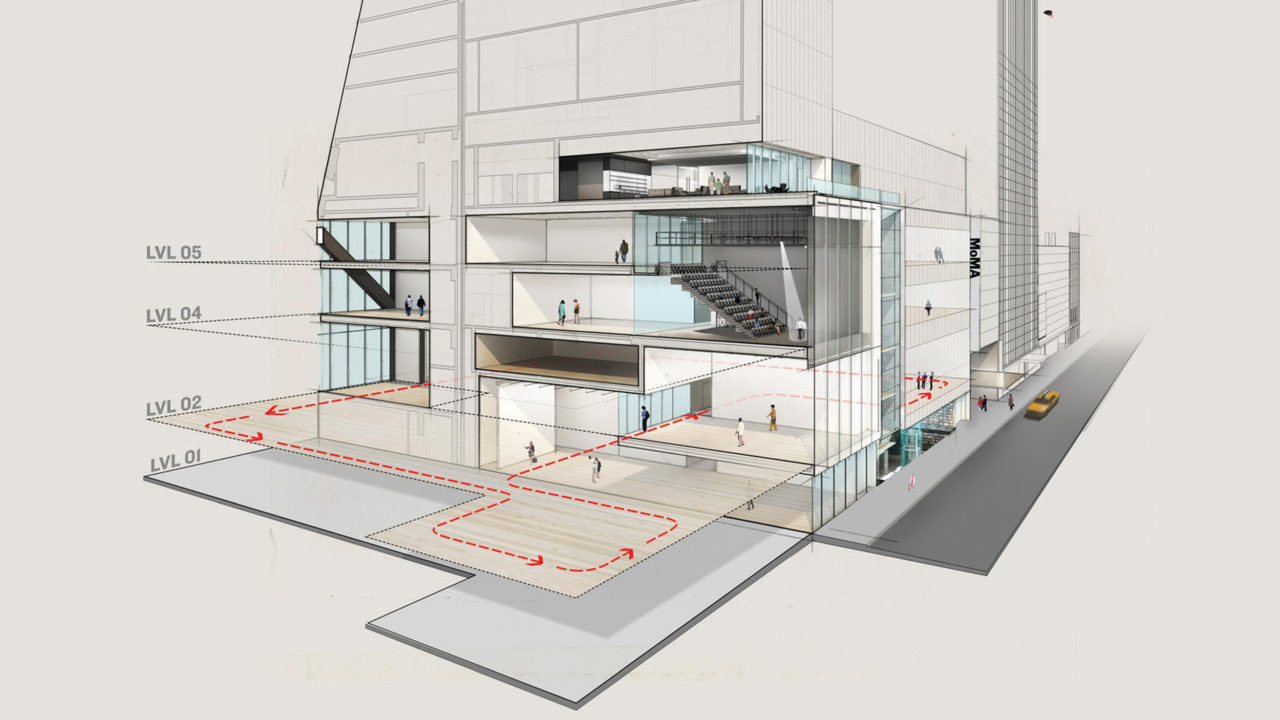

As DS+R partner Charles Renfro recalls, “We convinced the museum, after much haranguing—and them with much hand-wringing—to allow us to drop the bookstore one floor.” The old book stacks, he says, were an obstacle to circulation and street-level visibility. Enhanced ground-floor circulation outweighed the assumption that basements are bad sites for retail. Assigning access, comfort, movement, and sightlines a higher priority than souvenir sales is typical of this project; as the curators sought sufficient space to display more of MoMA’s collection and diversify its exhibitions, DS+R and Gensler focused their interventions on the visitor’s experience, from the grand gestures to the invisible determinants of ambience.

MORE TRANSPARENCY, MORE POROSITY, MORE FREEBIES

“The effort,” Renfro says, “was to reinvent the details of MoMA, which were always crisp, but to make them perform more technically by pushing the limits of these materials.” The most dramatic new features, one vertical and one semi-horizontal, are, respectively, the six-story Blade Stair in DS+R’s new western building, organized around a six inch-thick steel slab suspended from the roof, and a 37-foot, 95,000-pound main entrance canopy, also of stainless steel and suspended on tension rods, slicing through the glazing and “levitating over the street with a 26-foot cantilever.” Both adhere to a classic modernist aesthetic of clean lines and industrial precision.

The main entrance on 53rd is now double-height, mirroring the one on 54th. (“Taniguchi thought 54th Street might be the main entrance,” notes Gensler principal Madeline Burke-Vigeland, AIA, “but with the subway on 53rd Street, New Yorkers just don’t do that.”) After a brief compression/release sequence, one finds a lobby no longer clogged by ticketing queues; that function has been moved aside to a dedicated east-west corridor, aided by kiosks offering electronic ticketing in multiple languages. Furniture softens and domesticates this space, offering a living-room atmosphere for planning one’s itinerary before exploring the galleries or resting up to minimize “museum fatigue” later on.

The building opens itself to passersby, beckons them in, and presents visual interest in pre-ticketed space. The Sculpture Garden has been unticketed since 2015; “this ground-floor accessibility,” Renfro says, is “an expansion of that ethos.” The ambition “to bring art back to the city and back to the streets of New York” entailed strategies to reduce the barrier between the have-tickets and the have-nots, including artworks visible in the lobby and along the 53rd Street façade, plus portals allowing views to the second-story atrium, a Daylit Gallery along the façade, and the garden. Street-level galleries, including a double-height Projects Gallery equipped for multimedia works, are free to the public and have two entrances in the west lobby. The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio, a double-height multipurpose black box on floors four and five accommodating the performing and time-based arts, faces 53rd through a curtain wall, increasing museum-street porosity.

Renfro describes a balancing act, respecting MoMA’s past and the predecessor building’s essential features—Taniguchi’s vast atrium remains “the heart of the building”—while integrating and recombining elements, in keeping with the curators’ choice to rehang the collection with genres mixed, disciplinary barriers dissolved, and selections periodically rotated. The architects studied the building’s evolution, from its 1939 design by Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone through extensions by Philip Johnson (1964) and Cesar Pelli (1984), then Taniguchi’s renovation. Their material choices stress continuity with past conditions: a grayscale color palette; ample woodwork in public areas, including maple veneers in the entry with noise-dampening micro-perforations, and new white oak flooring, maintaining four-inch board widths in older galleries to contrast with eight-inch widths in the new west wing; a reinterpretation of a marble wall from the Goodwin/Stone building, now black and white rather than colored, as a recurrent ornamental motif; and a restored Bauhaus Stair linking the lowest three floors, paying elegant homage to Walter Gropius’s building in Dessau, Germany.

GET THY BEARINGS, INCLUDING DIAGONALLY

The main gallery floors two, four, and five each arrange galleries in loops (with occasional offshoots) through the Taniguchi building and the two new components, the Jerry Speyer and Katherine Farley Building (DS+R’s new segment framing the Blade Stair) and the David Geffen Wing of spaces inside the 53 West 53rd tower by Jean Nouvel. Fusing circulation with perception, the walkways and atrium offer frequent surprise openings and sightlines between floors. “We’re very interested,” Renfro says, in “diagonal connectivity between spaces and actually bringing a friction of the different kinds of activities that are happening here so the circulation space is in fact also the display space. We weren’t interested in making it the hallways or atrium and then galleries; we were actually interested in making everything become one.

Since the main gallery floors organize collection elements chronologically, he notes, “in the new building, those operations happen diagonally from gallery to gallery, and from the studio space to the gallery,” so that “we essentially break down that chronological consistency and allow the museum to start to program up and down, so new affiliations can be made.” Visitors have diverse choices for circulation, and with more views onto major internal elements and the exterior, their sense of an implicit 3D grid can be stabler, aiding orientation in spaces that have long been easy to get lost in.

The curtain-walled Blade Stair, linking Taniguchi’s building with the Farley Building laterally and connecting all gallery floors vertically, is an important new circulation path near a new core with two adjacent elevators, essentially a secondary atrium. Visible from both 53rd and a pocket plaza across the street, the Blade Stair is “the only part of MoMA that has space in front of it,” Renfro notes, “and in our effort to relieve the pressure, but also to make it feel more intimate, we wanted to use that space as an extension of the museum experience.” This stair, the Bauhaus Stair, and the new elevators all help relieve congestion in the older building, where the escalator stack and elevator east of the atrium have frequently been pinch points.

INVISIBLE SUBTLETIES

“One of the things that’s most remarkable about the project,” says Burke-Vigeland, “is what you don’t see.” A pair of large portals connecting the Farley Building to the Taniguchi to its east and the Geffen Wing to its west are painted black up to the ceiling, demarcating DS+R’s space. These portals also conceal important components, the results of tight-knit teamwork among the architects, the Department of Buildings, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, and 53 West 53rd developer Hines. “Buried there are fire shutters and doors within doors and lots of mechanical items within those thick walls,” Burke-Vigeland points out. “That circulation path was so important to the success of this design that there’s so many details in that, to get it right and get it seamless.” (The DS+R/Gensler partnership, she notes, was one of several complex collegial ventures between the firms, closer than arrangements where a design architect hands drawings off to an architect of record; a Citrix platform gave both offices simultaneous access to the working model.)

Gensler’s expertise in accessible design has meshed well with MoMA’s commitment to reducing barriers and ensuring a dignified experience for all visitors, regardless of impairments. These efforts extend well beyond wheelchair access, addressing differences in hearing ability, vision, age, mobility, gender, intellectual and developmental disabilities, and other factors. Francesca Rosenberg, director of MoMA’s Community, Access, and School Programs and member of its Accessibility Task Force (an outgrowth of its longstanding service to the disabled dating back to 1945, when it launched the War Veterans’ Art Center), served on Gensler’s 2018 inclusive-design roundtable, which advocated a systematic approach to removing both physical and perceptual barriers. The renovation implements this philosophy through the more open wayfinding plan, clarified signage, contrasting surfaces to enhance visual perception, an induction hearing-loop system, and accessible, height-adjustable furniture. Describing MoMA as “an enlightened client,” Burke-Vigeland notes that “whenever you’re dealing with a big public space and trying to address individuals of all needs, it’s not an easy thing. The entire team did their best to address it in a way that was inclusive and not developed as an afterthought.”

With performative works and multimedia moving into spaces previously hosting painting, sculpture, and design artifacts, the building’s acoustical properties become nearly as important as its sightlines and lighting. One space requiring special attention to sound is the Kravis Studio, configurable as a theater seating 105 on a raked platform, with a walkable suspended ceiling grid, solar shading, blackout curtains, variable-level acoustic drapery, and a cable-hung double curtain wall with an occupiable cavity, providing protection from street noise as well as daylight control. DS+R project architect Andrea Schelly compares the studio to “a Swiss watch,” a box-within-box space acoustically isolated on all six sides; “the floor is a floating slab with end frames on neoprene,” she says. “This is a dance floor with some resilience to it and deployable, tunable acoustical baffles.”

Acoustic engineers Cerami and Associates consulted not just on the studio, with its need for theater-quality sound clarity, but also on the Blade Stair, where microperforated maple lines the atrium and contributes to a calm atmosphere. “We did a lot of acoustical modeling,” says CEO Victoria Cerami, treating MoMA and DS+R personnel to 3D computer simulations of the spaces based on benchmark data representing variable crowd spatial dispersions and internal or street noises. Cerami’s laboratory allows designers and other clients to experience a space’s distinct acoustical signature, much as a lookbook gives options for choosing visible features. Associate principal Matthew Schaeffler notes that there are “plenty of museums that we’ve done where little attention was put to something like a stair. It’s almost on the back plate; it’s not a design feature.” MoMA, in contrast, viewed acoustics as an essential aspect of visitors’ experience. The Blade Stair, Cerami says, is “beautiful, and we are invisible to that stair, but yet we’re very visible, because it’s so wonderful in the way it sounds. It’s a very magical experience on the stair, but I don’t know that anybody could actually pinpoint why.

Much of what makes the new MoMA promising involves factors that are hard to pinpoint. Some are matters of nuance: Renfro reports that they changed all galleries’ lighting to 3000° Kelvin, a crisper color temperature. Others, like the immediately iconic steel plates, are more obvious. Many bear in mind the museum’s broadly democratic objective “to bring more of the collection to the public than had ever been shown, and to redress some of the issues of ‘white/male/European’ that had so dominated the way MoMA had been for 80 years,” he observes. “There are more people like more New Yorkers represented in the galleries: more women, more people of color, more outsider artists, artists that were not trained in art. Gone are the preachy art-historical wall texts, and now you find more circumstantial wall texts, which historicizes ideas and not trends and art movements.”

The new building deploys its subtleties purposefully, refraining from shouting at its visitors, widening opportunities for more people to explore ideas. People who have previously felt excluded from the museum, or from the art world in general, may find its new version both surprising and welcoming. So do insiders, Renfro finds, even world-weary ones. “I’ve heard back from some of my artist and art-history and critic friends that they finally feel like the museum has returned, and they want to go there again,” he says. “And that’s almost the best validation we could hope for.”

Project Credits

Architect: Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler

Director, Real Estate Expansion, MoMA: Jean Savitsky

Construction Manager: Turner Construction Company

Retail Consultant: Lumsden Design

Lighting Designers: Tillotson Design Associates (public spaces), Renfro Design Group (gallery spaces)

MEP/FP/IT: Jaros Baum & Bolles

Structural Engineer: Severud Associates

Façade: Heintges Consulting Architects & Engineers P.C.

Sustainability: Atelier Ten

Security: DVS Security

Acoustics/Audiovisual: Cerami Associates