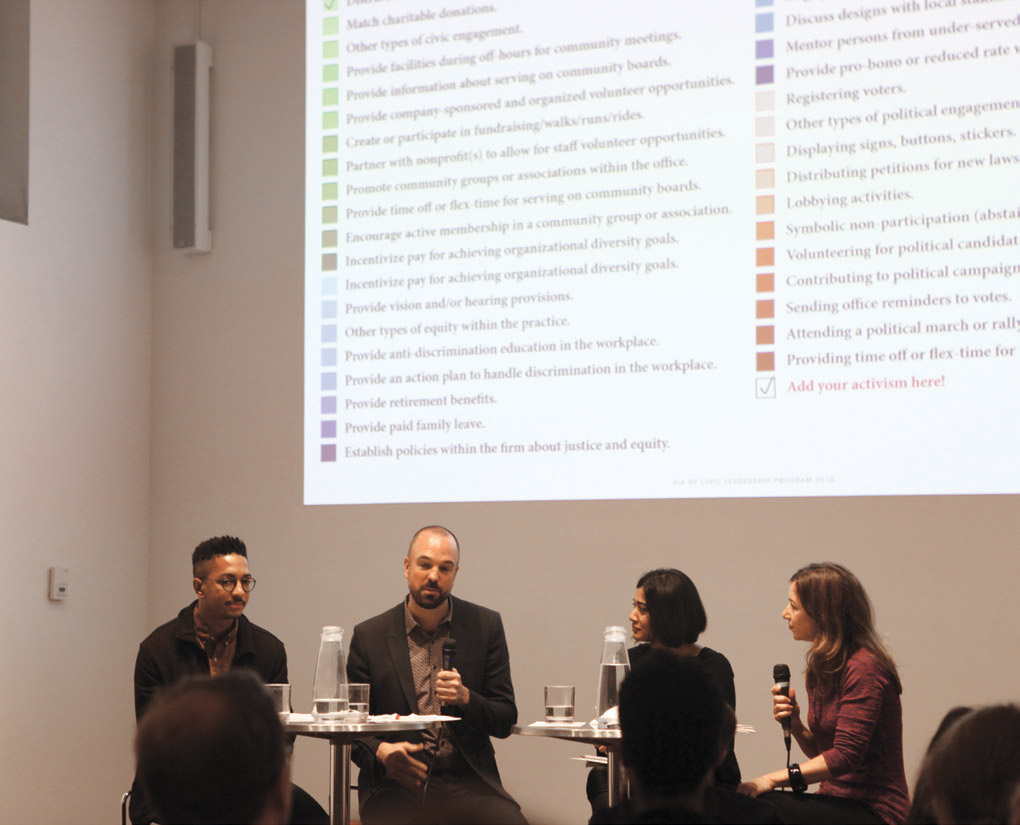

A palpable enthusiasm was evident among the attendees gathered for Civic Engagement in Practice, a program held by AIANY’s Civic Leadership Program (CLP) just five days before the U.S. midterm elections. CLP was created two years ago, in part, “to cultivate a class of emerging architectural professionals into civic leaders,” according to its mission statement. The three assembled panelists offered a formidable array of projects and concepts that were highly engaged with designated communities and proposed serious social impact. But during the discussion after the presentations, Christopher Rice, a senior urban planner for WXY, and Weston Walker, who heads Studio Gang’s recently established New York office, found themselves pushed to the center of architecture’s often liberal discourse relative to Priyanka Shah’s philosophical ideals. Shah was representing the Architecture Lobby, the non-profit grassroots organization of architectural workers, and the field’s social democratic voice. Discussing firm culture, she posited, “If working conditions are too inequitable, the idea of engaging in social and civic projects is not possible.”

Accordingly, CLP’s recent survey of AIANY firms’ propensity toward civic engagement, political activism, and workplace equity revealed the latter to be the lead concern. Equity starts at home—especially if the goal is to bring notions of engagement to profitable firm projects. “It’s about being a content-driven firm versus a service-based firm,” says WXY’s founding principal, Claire Weisz. But first “you have to figure out what your principles are.” A project team ensconced in equitable practice has the foundation to speak to content that allows partnership with public agencies, rather than waiting and hoping for a client interested in creating social impact.

RIPPLE EFFECTS

Staff interest in equity is part of the office dialogue at WXY. As project leader of D15, the firm’s ongoing partnership with the NYC Department of Education (DOE), Rice brings expertise and ideas derived in part from his work with BlackSpace, a collective of black designers and community planners that seeks to amplify black agency. “Bridging the gaps between policy, people, and place,” explains the group’s website, “allows for the greater understanding, access, and cooperation needed to address inequality and injustice.” Rice’s design investigations into the social and spatial organization of cities work to promote social inclusion and address historic racial inequities. He also helps raise awareness by representing WXY publicly at AIANY events, where he discusses the work of BlackSpace as well as firm projects.

“Projects comes from problem-seeking,” says Weisz, referencing data gleaned from the case studies of Proactive Practices, a research initiative that collects and presents business models for engaging in public interest design. Weisz is an advisor to the organization, which has spent three years examining new approaches for establishing progressive design practices. As with determining a practice’s principles of staff equity, the team must identify elements that constitute the work to be done. “What issues do we want to address? Where can we address those issues?” Weisz asks to begin the process. “What do you use a commission for? To teach? To create models that can be replicated?”

From her perspective as a firm director, the success of such projects requires architects to take an instructive role. For D15, WXY guided the DOE to rethink the complex process of placing middle-school students throughout the city’s District 15—which includes Boerum Hill, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Fort Greene, Gowanus, Kensington, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, and Red Hook—to enhance diversity, opportunity, and resources for those communities and citizens. “We had designed a couple of schools,” says Weisz, “so we knew that what happens before the decision is made to build a school is crucial to the physical design. How does the school serve the students’ entire network? How do you weave connections between people?” She stresses the need for planners and designers to work together. “Architecture is a humanist field,” she says. “Social research is becoming a factor. How do built environments affect people?”

ENGAGE THE EXISTING

The Architecture Lobby offers a manifesto as a blueprint for such practice. Item 3 reads, “Stop peddling a product—buildings—and focus on the unique value architects help realize through spatial services.” It’s an idea Eran Chen, founding principal of ODA, had in mind when working on Unboxing New York, his new book on the evolution of the cityscape. “In our cities, we see an invasion of buildings that ignore the existing community,” he says. “We have to rethink our projects to enhance what already exists.” Such rethinking was key for Denizen Bushwick, a multiuse development on the former site of Brooklyn’s Rheingold Brewery, which incorporates one million square feet of residential space (20% of which is designated affordable housing); common green space, plazas, and promenades; and public art commissioned from neighborhood artists. The art component of the project was a natural outgrowth of Open, ODA’s year-old non-profit arm that collaborates with artists and agencies in areas in which the firm has work. “Open was intended to reach out to community leaders to figure out how built projects can engage with the existing locality and explore notions of ownership,” says Chen. For Denizen Bushwick, ODA and Open crossed paths, allowing designers and planners to investigate the degree to which the two could collaborate. Bringing the for-profit and non-profit entities together allowed the firm “to kill two birds with one stone,” according to Chen, “in that we can coordinate art projects with new build projects.”

While ODA set up a non-profit ally, which works independently as well as being a firm partner, Boston-based MASS Design Group—one of the case studies of Proactive Practices—has incorporated itself entirely as a 501(c)(3). “A few elements about how non-profits are organized lend themselves to the way we want to work,” says MASS Senior Director Regina Yang. “Non-profits are accountable to the mission of the organization; for-profits are accountable to the bottom line.” Garnering resources, from budgets to fair pay, is often an architecture project’s greatest obstacle.

When work is funded by a client’s resources, there may be limitations to the actions architects might otherwise take. MASS opted to bypass that hurdle, allowing an embrace of different benefits: “Being a non-profit opens us up to receive outside funding and grants,” says Yang. “It allows us to do research in ways the market doesn’t typically support. In terms of our larger vision, we’re trying to show a different model of practice. We’re trying to build a collective of practitioners who are trying to think of new ways to develop process.”

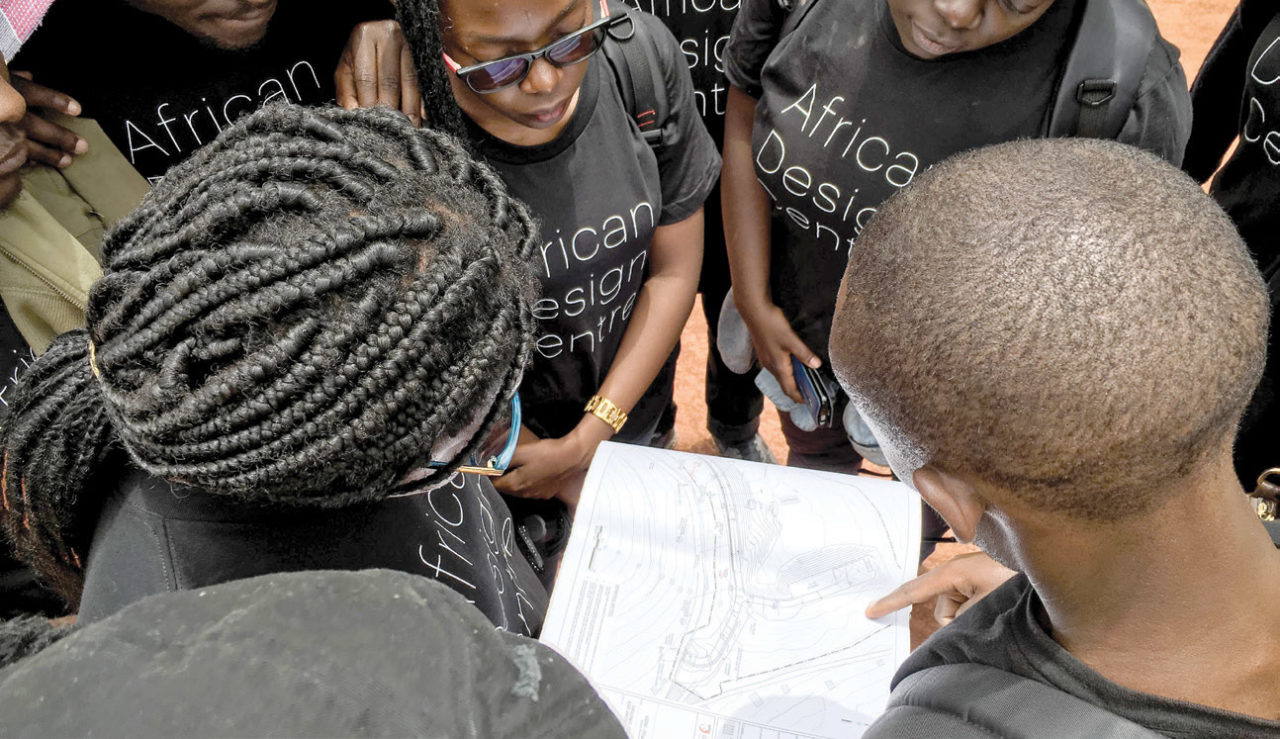

Of course, all-encompassing projects are greatly appealing to both emerging and established practitioners. With MASS, for example, the lead question regarding the Ruhehe Primary School in Rwanda’s Musanze District became, “Can a school’s design serve as an example for improving education?” But in an egalitarian ideal of a workplace, where all ideas warrant consideration, how do team members avoid falling into either the conventions of hierarchy or the pitfalls of design by committee? “Our pride and egos take a back seat to our desire to serve a community and achieve goals,” answers Yang. “We’re pretty clear in articulating our work process to new members, so people know what they’re getting into. We don’t have strict methods, so each team can mold the workflow for the partner [client] or the group.” As for the notion of hierarchy, the organization is developing strategic planning councils internally. “We want to make sure young leaders are able to exercise their leadership opportunities,” says Yang. Meanwhile, architects with many years of experience can impart their wisdom during leadership discussions. The notion of “exceptionalism doesn’t help us,” said Architecture Lobby’s Shah during the panel discussion, referencing Item 6 of the organization’s manifesto to “demystify the architect as a solo creative genius.” She suggested replacing the starchitect with the citizen architect. “We have to enlarge our claim,” she said, “and become political by virtue of our choices.”

CITIZEN ARCHITECT

When asked what drove WXY to bring civic projects to the fore of its practice, Weisz doesn’t offer the expected answer about finding meaningful work. “The impetus was knowing communities were the clients of the future and should be put in a position of being great clients for design,” she says. Recent WXY civic-engagement projects have led to designing the engagement itself, the result of which are policy changes that foster specific initiatives. The firm’s latest challenge is developing methods for working with communities and stakeholders on questions that evade easy answers. Working in the context of the East Harlem Community Plan, a rezoning proposal that examined how best to build affordable housing and address issues of density, designers empowered citizen partners with voice and structure to address needs the community is uniquely able to identify. Beyond typically known building issues, the project “was about giving local experts a platform to figure out what they needed to get done,” says Weisz.

No stranger to working with government agencies, architectural scholar and practitioner Lance Jay Brown, FAIA, a former AIANY president who currently co-chairs the Design for Risk and Reconstruction committee, has been mining the seemingly insurmountable issues of disaster preparedness since 9/11. Realizing that architects should be part of the cadre of scientists, engineers, planners, and thinkers engaged by government to prepare built landscapes for catastrophic events, Brown has helped alter the way the city does disaster and environmental business. Brown was in the room when Mayor Bill de Blasio committed New York City to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% by 2050, a goal adopted by the Paris Agreement of 2015. “Not surprisingly, there was an oil-industry guy from the New England Home and Heating Association at the meeting, asking how the home heating-oil industry could contribute to the cause,” recounts Brown. “Of course, the obvious answer to him was, ‘If we do this right, there won’t be a need for home heating oil in 2050. You’ve got 30 years to figure out how to pivot your business.’ It takes a certain amount of stalwart bravery to move this dime.”

Citizen architects may take part in political conversations, but bringing politics back to the office remains fraught, according to the CLP survey. For example, only 18% of firms responding support the display of political signs, buttons, stickers in the workplace. However, creating space and platforms internally for what may initially feel like difficult discussions is central to supporting equity at the practice level, and, by association, the work that teams do out in the world. From the CLP dais, WXY’s Rice offered a way forward: “We have to learn to lean into the discomfort of tension created by differing views.”