Angie Lee, AIA, IIDA, principal and design director of interiors at FXCollaborative, was giving a presentation to clients when she realized she was playing a game of color-palette politics. “There was this light terra-cotta color, and I found myself calling it ‘light red’ in response to someone grumbling, ‘Is that pink?’ Finally, one of the male clients said, ‘You know, I like pink; you can stop calling it light red.’”

I’m talking with Lee in the huge common room of The Wing Soho, a women-only workplace and social club that was founded in 2005 and has opened locations in D.C., New York, and San Francisco. “Without a doubt, pink for me is something that has been weaponized against women,” she says. Girls get pink toys, pink clothes, pink play kitchens; the fact that the color is absent from traditional corporate suites “is tied into who belongs in the workplace,” she says.

As we scan the room, pink (and pastels and jewel tones) seem to have been reappropriated by The Wing’s career-driven members, and is used on the company’s logo, the shelves of its female-focused library, and the plush banquette seating full of women working with other women. (The design is a collaboration between Wing founders Audrey Gelman and Lauren Kassan, interior designer Chiara de Rege, and architect Alda Ly.) Nobody here would say using pink decor has solved centuries of entrenched gender inequality, but it is a signal that women are beginning to expect a different type of space in which to work and live. It’s a space that has, for instance, a private room where new mothers can pump breast milk just down the hall from the conference table. This location is also adding a daycare in January.

We poke our heads into a lactation room, with comfy velvet-upholstered rattan seating, a changing table, and shelves stocked with a breast pump, cleaning wipes, and a tiny refrigerator, and I flash back to the last 10 months of lugging my own breast pump around the city. I’d left my previous coworking space in part because it didn’t have a lactation room. Hotel restrooms, spare conference rooms, and even (thanks to a nine-volt adapter) parked cars had become best-case scenarios for expressing milk for my infant son while I was away from home during the day. A fellow mom at FXCollaborative, where I edit white papers for FXPodium, had offered me the firm’s own lactation room when she caught sight of the telltale black Medela bag so many women tote with them to work. Lee related her own story of pumping in a storage closet at a former office, a familiar experience for many new mothers.

We pull ourselves away from The Wing’s lactation room and continue our tour. We’re here as guests of Lee’s colleague, the firm’s business development coordinator Julia Gamolina, who is a founding member of The Wing and now uses the space to host interviews for her online magazine, Madame Architect, which features female architects from all walks of life. “I used to do interviews at the architect’s office, and now I do them almost exclusively at The Wing,” says Gamolina. “People really take up space, sit back in the chairs, and are themselves.”

The Wing offers a sort of playbook on how to rewrite the story of women in the workplace; surely a lot of this could exist in an all-gender workplace, too, with a little reordering of the status quo.

For Lee, this is the moment for architects to take part in this activism and develop a new lexicon for themselves. “We talk about weaving a narrative to tell a story for our users,” she says, “but in fact the way we’re trained as architects is embedded in deep traditions of male-dominated culture.” She remembers sitting in architecture school classes where decorative design moves were described as referential. “There are code words for ‘it’s too feminine.’ When we talked about architecture with a capital A, it was based on an international style where any embellishment was frivolous and unnecessary.”

Next year, Lee hopes to present two talks tentatively titled “Vocabulary Detox—Reinventing Leadership” and “Design Thinking as Activism,” the seeds for which were sown more than a year ago as story after story of sexual misconduct broke in the media. How many of these wrongs could have been averted if the offices, campuses, and streets where they were perpetrated had been designed to convey equality and safety? Architects are in a unique position to physically reshape the environments that are complicit in our experiences of inequality. Design safe, equitable spaces, and it’s likely that behavior will follow suit.

Fueled in part by the current political atmosphere, architects are approaching the challenge of designing inclusive spaces from several angles. The profession itself, however, is living in a glass house—a year into the #MeToo era, many architects cite the news of sexual assault allegations against Richard Meier as a catalyst for conversations about architects’ roles in fostering gender equality and inclusivity.

At the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF), this conversation is almost two decades old. Founded by Willis in 2002, the non-profit foundation works to advocate for and recognize women in architecture. Sometime after Harvey Weinstein’s crimes sparked the #MeToo movement movement and before the Meier news broke, BWAF began supporting women who had come forward to recount their stories of inappropriate behavior within their architecture offices. “We have this year worked to get the AIA code of ethics to include sexual misconduct as a disbarrable offense,” says Cynthia Phifer Kracauer, AIA, who is BWAF’s executive director. “We are also very active in working with a range of different attorneys, human resources people, prosecutors, and psychologists to craft best practices for training and talking about it.”

There seems to be a wellspring of support for this type of conversation from top architecture firms, including those directly affected. In December, BWAF held a roundtable to coincide with Art Basel Miami titled Women Up: Successfully Navigating the #MeToo Business Environment to discuss how architecture firms are addressing gender issues in the wake of so many high-profile sexual harassment cases. The speakers list included Vivian Lee, a principal at Richard Meier & Partners; Pat Bosch, design director at Perkins+Will; and Suzanne Pennasilico, chief human resource officer at SOM.

Architects like Kracauer, who entered higher education around the time that many institutions were becoming coeducational, experienced firsthand the way architecture could discriminate against people. At the recent She Roars women’s conference held by her alma mater, Princeton, which began admitting female students in 1969, Kracauer said she found one topic that united the women of her generation: “Where did we go to the bathroom when we were first at Princeton? There was an absence of accommodation. They brought women in, and I guess they didn’t think we peed.”

She remembers that Firestone Library had two toilets for women, both labeled “Staff,” a relic of a time when librarians or administrative employees were the only women around. She and fellow architecture classmates finally “liberated” the men’s room, flipping a sign to read “Women” when they wanted to use it.

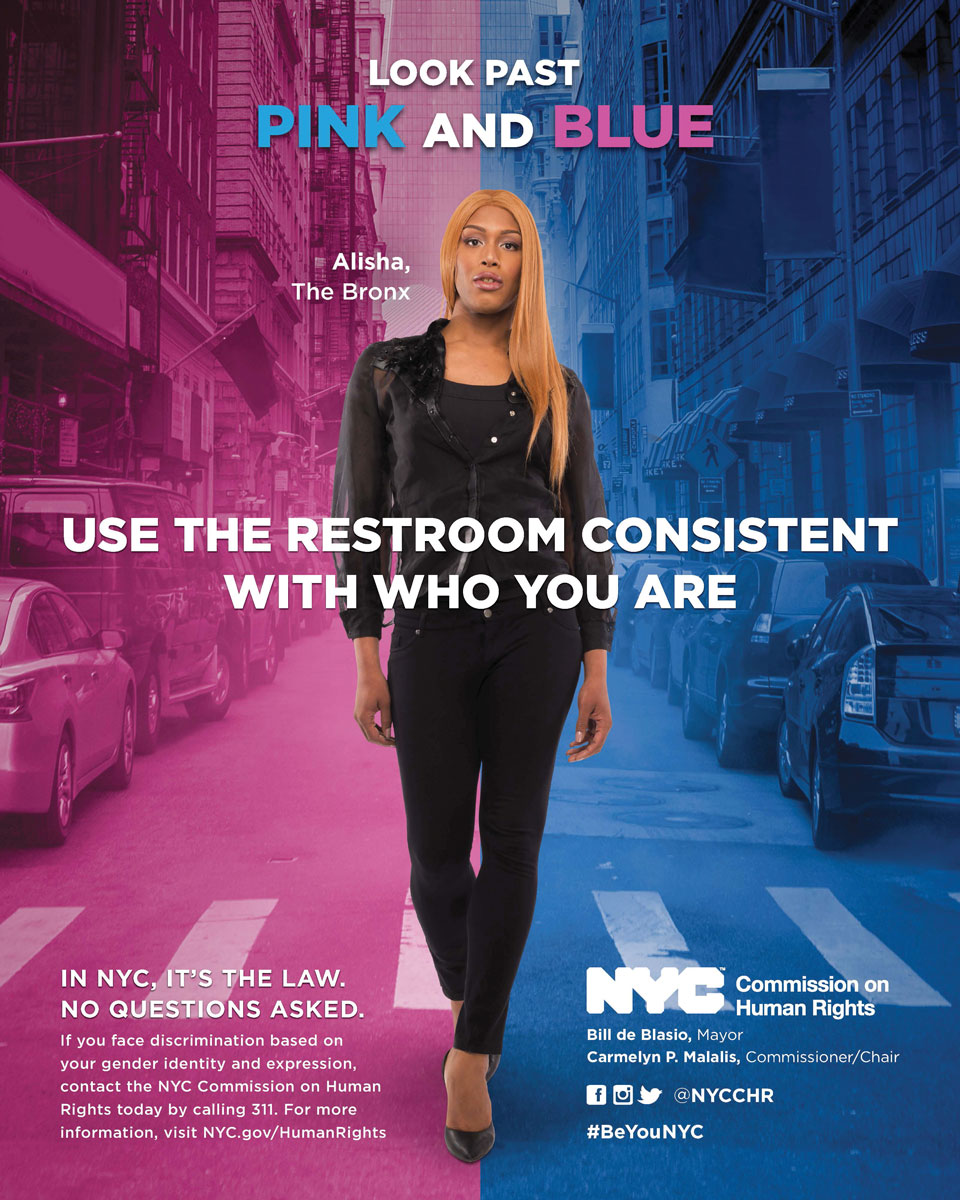

Perhaps no other room signifies the struggle for civil rights and societal inclusion more than the bathroom. Within the architecture profession, bathrooms have become a point of departure into a much larger conversation about inclusive design. While racial minorities, women, and people with disabilities are now accommodated under U.S. laws, the designs and societal norms surrounding bathrooms are only just beginning to consider the inclusion of transgender and gender-nonconforming people.

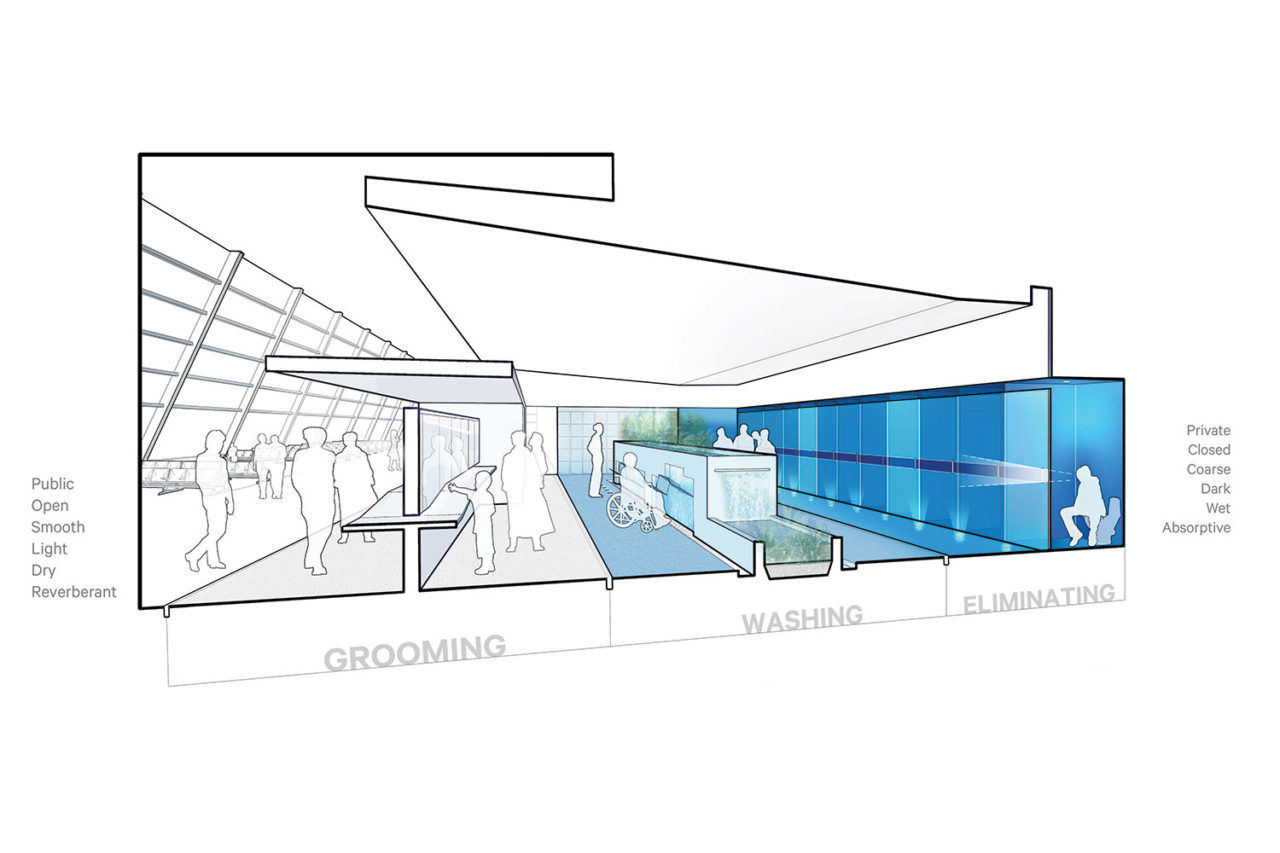

One breakthrough project in the field is Stalled!, which won an AIA 2018 Innovation Award. The project was started by architect Joel Sanders, AIA, transgender historian Susan Stryker, and legal scholar Terry Kogan as a response to court cases seeking to overturn President Barack Obama’s Title IX protections for trans individuals’ ability to use sex-segregated public toilets that align with their gender identity.

The initiative moved beyond its academic origins quickly, and is now three-pronged: it aims to develop Best-Practice Guidelines for all-gender restrooms; amend the International Plumbing Code to allow for all-gender, multiuser restrooms; and raise awareness with designers, the government, and other institutions like universities and museums.

The prototype for Stalled! is an all-gender bathroom that moves away from the single-user design that can be seen as stigmatizing, especially for trans, non-gender conforming, and disabled people who can feel singled out. Instead, the Stalled! design proposes a multiuser solution that treats the bathroom as an open space, with common areas for washing and grooming and full-height toilet stall partitions to maximize user privacy.

The project hopes to catalyze larger conversations about inclusive design. “More broadly we see that Stalled! is also a platform to raise awareness in the design community and the public about the broader issue of equitable public space design,” says Sanders. He has founded a new design consultancy, MIXdesign, to pursue work that reflects equity within the entire built environment, not just bathrooms. “Universities and companies are devoting a lot of resources to diversity and inclusion,” he says. “This amounts to human resources and hiring practices, but we’re trying to help stakeholders think of the design consequences of this. Historically, the default user of buildings is almost unconsciously an able-bodied, white, cisgendered person. Moving forward, we need to think there’s a wide spectrum. We need to expand beyond ADA and go beyond checklists to meet the needs of a much broader audience.”

In this vein, design offices could hold charettes to model shared armrests on trains or planes that don’t invite unwanted touching, office designs that discourage inappropriate behind-closed-doors interactions, and public spaces with proper lighting. Consider Cynthia Nixon’s request before her gubernatorial debate against Andrew Cuomo: a thermostat set at 76 degrees. At the beginning of fall, a friend who works at an architecture firm texted me that she’d run out to buy a sweater at lunchtime; her office was an icebox and she, like many women there, needed layers to be able to work comfortably as the air conditioner blasted. I later read on the Society for Human Resource Management website that most office thermostats are calibrated according to a 1960s-era ASHRAE model that uses the metabolic rate of a 40-year-old, 154-pound man.

For Lee and other architects I spoke with, the goal is that inward-looking conversations about inclusion and equality within the profession will imbue external work with clients. Part of that work is getting clients to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. “I still hear today from clients who are men wondering why they have to give up so much space to one woman who had a kid last year,” says Lee. But many clients are ready for these conversations. She recently worked with Amtrak to design a first-class lounge in Moynihan Station that will include a mother’s room.

Success may be a challenge to measure: Can architecture really balance the specific needs of so many different groups? Some worry that a space designed to accommodate everyone will not be a true sanctuary for anyone, while proponents of “intersectional” design argue that addressing ingrained biases can improve life for all citizens. While architects can research and advocate, it is ultimately up those commissioning work to invest in inclusive design. Architectural responses to today’s diverse gender landscape remain largely on the drawing boards, but there is hope that if buildings can be good citizens, perhaps their occupants will be, too.