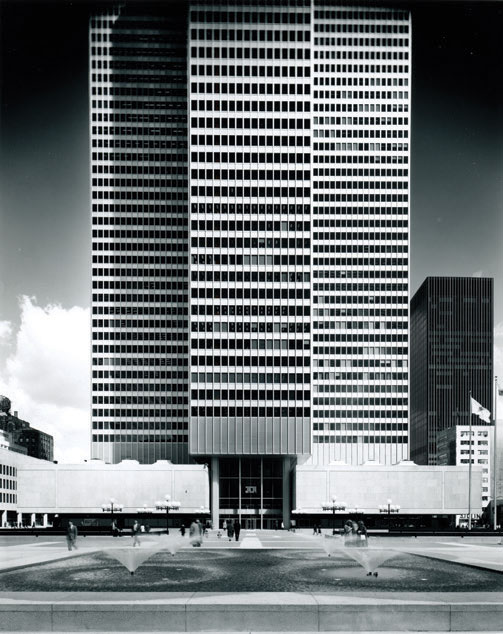

Henry N. Cobb has been practicing architecture for nearly 70 years, almost all of them at the practice founded by I.M. Pei and known since 1989 as Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. His built projects include skyscrapers, notably the John Hancock Tower in Boston (now called 200 Clarendon Street) and 200 West Street (the Goldman Sachs headquarters) in Manhattan, and a number of institutional buildings, including an addition to the Portland Art Museum in Maine and the John Joseph Moakley U.S. Courthouse on Boston’s Fan Pier.

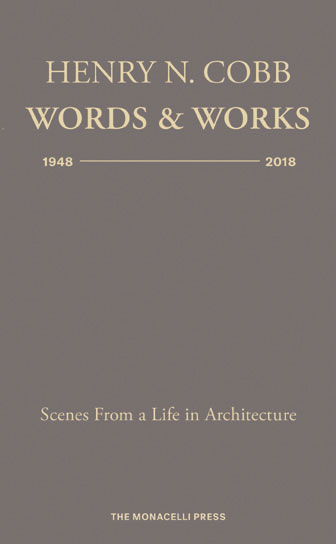

Cobb, now 92 and widely known as Harry, studied architecture at Harvard in the 1940s, and in 1980 returned there as chairman of the architecture program, a post he held for five years. In October, Monacelli published his first book, Henry N. Cobb: Words & Works 1948–2018: Scenes from a Life in Architecture. A compendium, the volume features photos, drawings, essays, speeches, interviews, and even a toast Cobb gave on Pei’s 50th birthday. Its page size, 4 1/2 by 7 1/4 inches, was derived from the books of writer and critic Edmund Wilson published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a dozen of which Cobb has on a shelf in his home library.

FB: Is the digital age making architecture books obsolete?

HC: That might be true of monographs, but mine is not that. It’s a book, and books will always be important. Part of the pleasure of this book reflects my obsession with the Edmund Wilson format, which makes it rest so easily in the hand. Library of America books are a little bigger, and they don’t rest in the hand as well.

Will there be a digital edition of this book?

I hope to have multiple printings, but I don’t want to have a digital edition. You lose too much. This book is made to be dipped into. You can’t dip into a digital book.

How did you get Monacelli to agree to this format?

I brought an Edmund Wilson book to a meeting with Gianfranco Monacelli. He took it in his hand, opened it and shut it, thought about it, and then said, “Forty-five dollars—that’s the most I can charge for this.” And that became the price, though of course on Amazon you can get it for much less.

You mentioned the book took more than 20 years to complete. Why so long?

The book always took a back seat to my practice, which I’m still very much involved in.

You’ve mostly done commercial projects, while Pei tended to focus on museums and other institutions.

He never had a passion for the large commercial projects. I did. Though I’ve also done many institutional buildings, I’m not so much a formgiver as a problem solver. Pei is a formgiver. Gehry is a formgiver. Venturi was a formgiver. I know my limitations.

But you’re also an intellectual.

As I believe the book shows, it’s very important for architects to be reflective, to step away from their own work and be selfcritical.

Tell me about what you’ve called “The First (and Last) Meeting of the Modernist Reading Group,” a gathering in 1986 at which you allowed John Hejduk, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, Jeffrey Kipnis, and others to critique your design for an addition to the National Gallery in London, which lost to the Venturi, Scott Brown entry.

It may be the most interesting chapter in the book. My daughter Emma came across this tape, which I had made but forgotten about. It was a conversation that was not intended to be published, and it was just everybody letting it all hang out.

Some of it was at your expense.

Yes, but justifiably so. I lost the competition, and in my view, Venturi, Scott Brown deserved to win it. My entry addressed the place—that was its strongest quality—but it didn’t address the time. I might have gotten there, but I didn’t get there during the competition. But the critique isn’t the most important part of the conversation—it’s the exploration of the predicament of architecture at that moment that’s most important.

We recently lost Bob Venturi. Did his work have an impact on yours?

I was greatly influenced by his book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, but it would not have been as influential had Venturi not also been a great architect. When you put that book together with his mother’s house, you see not only a powerful theoretical proposition, but the application of that proposition in a compelling way.

You’ve spoken previously about problems of attribution at Pei Cobb Freed—specifically the crediting to I.M. Pei of buildings you designed. Has that all been sorted out?

Not entirely. It’s taken a new form. The problem now isn’t Pei’s getting credit for my work, it’s my getting credit for other people’s work. Much of my work is done in collaboration with my six partners and other colleagues, but the world isn’t interested in shared attribution. Since I lived though it [an attribution problem] and it shaped my life, I’m particularly sensitive to it, but that doesn’t mean I can always solve it. There’s still a cult of personality.

Does this kind of book contribute to that?

It’s not about me—it’s about what happened in architecture in my lifetime. I’m a kind of exemplar.

What’s not in the book?

A conversation devoted to the concept of the “combined work.” When you insert a building into a historic context, especially a tall building, you have to think about how that building is going to create a combined work with its neighbors. Although there are people in Boston who would probably take offense, I view the Hancock Tower and [Henry Hobson Richardson’s] Trinity Church as a combined work.

You’ll always be identified with the Hancock Tower.

My most important building in Boston is the Moakley Courthouse, not the Hancock. The courthouse is a flawed work, but it’s not about being perfect—it’s about addressing really important problems in the culture, in this case the role of the judiciary in our society. Hancock is the postcard building, but in terms of what architecture has to say about the culture, Moakley is the more important building.