Seen through the eyes of cable news producers, school board meetings are battlegrounds for the soul of America’s children. The reality is more nuanced, and more productive. In the current wave of school construction represented by the standout projects featured here, parents and officials agree that students deserve optimal physical conditions for learning. And while the following examples illustrate several phenomena, such as a STEM-adjacent interest in vocational training, they all espouse the belief that ecological building performance is vital to the occupants’ well-being—as well as an opportunity for kids to learn about green innovations firsthand. Read on for several examples of K–12 sustainability advances that have stoked ac-cord rather than contention.

Outward Bound

For St. Luke’s School, a private, independent school for grades K–8, ABA Studio’s vertical expansion of an existing academic building in 2017 allowed the West Village institution to approximately double its enrollment. According to Rajit Malhotra, the school’s chief financial officer and chief operating officer, development of the additional 19,000 square feet had been sparked by the school’s independence from its namesake church, which had taken place a half decade earlier. “Expanding the school size was core to finances, governance, and other elements of organizational stability,” says Malhotra.

Although the building project spanned years of effort, Malhotra notes that its realization also revealed that “the outdoor space allotted per child—primarily the school playground that was beloved by the community—significantly decreased.” In 2018, St. Luke’s School kicked off a new fundraising campaign, which yielded a replacement ground-floor playground designed by landscape architect MNLA the following year. The intervention was planned in collaboration with educators so that it would emphasize opportunities appropriate to the student body, such as coordination, balance, motor skills, and even conflict resolution.

For the three-phase project, St. Luke’s had diverted funding from a phase-two courtyard and amphitheater in 2020 to COVID preparations for in-person learning. “However, as the world quickly learned that being outside significantly increased safety during COVID,” Malhotra recalls, “we knew that even though it was expensive to fund both an outdoor and in-person experience, it was very important to move forward with both.” The school finished the courtyard and amphitheater, also by MNLA, while deferring the third phase. That project opened last fall. Designed by Marble Fairbanks and encompassing a multipurpose turf field covered by a metal mesh enclosure, as well as an outdoor learning zone that can double as an event venue, this third phase perches on the roof of ABA Studio’s expansion.

For young New Yorkers, access to the outdoors is not a thing of privilege. The city’s School Construction Authority (SCA) “has long had a steadfast commitment to creating healthy environments for teaching and learning,” says FXCollaborative Architects partner Ann Rolland. “The SCA’s design standards require daylight to all classrooms, stairs, and corridors; they also opt for walkable schools and require outdoor play areas in all their schools. The concept of connecting school to site, neighborhood, and city beyond is something they value.” In the FXCollaborative-designed Hunter’s Point South Primary School (PS 384), which opened in 2021, those concepts get a boost thanks to the 612-student facility’s adjacency to Hunter’s Point South Park Extension.

The five-and-a-half-acre park extension had just been completed when FXCollaborative began designing PS 384, says Rolland, adding that the project site represents “the precipice of the confluence of the East River and Newtown Creek.” The resulting building maximizes views to the south and west, while a play yard to the east connects the school to the neighborhood. FXCollaborative had also diagonally woven a lobby across the school’s ground floor to reinforce the connection between the park and the east-facing yard. For the overall plan, Rolland also notes that the design team “carved the circulation between the academic and the community functions” in the manner of a river current. To underscore the intimate relationship between natural and built environments, FXCollaborative selected an iron-spot brick façade that evokes the schist underneath New York City.

The work that has taken place at both St. Luke’s School and PS 384 is emblematic of a worldwide push to improve children’s access to nature. Biophilic K–12 design has been gaining acceptance alongside steadily growing evidence of its benefits, and the outdoor classroom movement has burgeoned since the start of the pandemic. How will these phenomena inform schools of the future? Recently unveiled plans for The British School in Tokyo, designed by Thomas Heatherwick, suggest a bold direction. Slated for an August 2023 opening, the new building for 800 students comprises planted balconies that ascend from the street in staggered formation.

Changing Perceptions—and Specifications

“There used to be a stigma associated with a vocational school—that it was for bad kids,” says architect Tina Stanislaski, who recalls touring an older New Hampshire high school that had relegated its technical classes to the basement. But the principal of HMFH Architects, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, also notes that the perception is shifting, as is corresponding demand. “There’s a whole population of kids who appreciate learning by doing, and there’s an influx of colleges that want to accept students with vocational experience,” Stanislaski says. Indeed, the Massachusetts School Building Authority (MSBA) currently has three vocational schools in its pipe-line, among them the HMFH-designed Bristol-Plymouth Regional Technical School, which went out for construction bids on July 1, 2023.

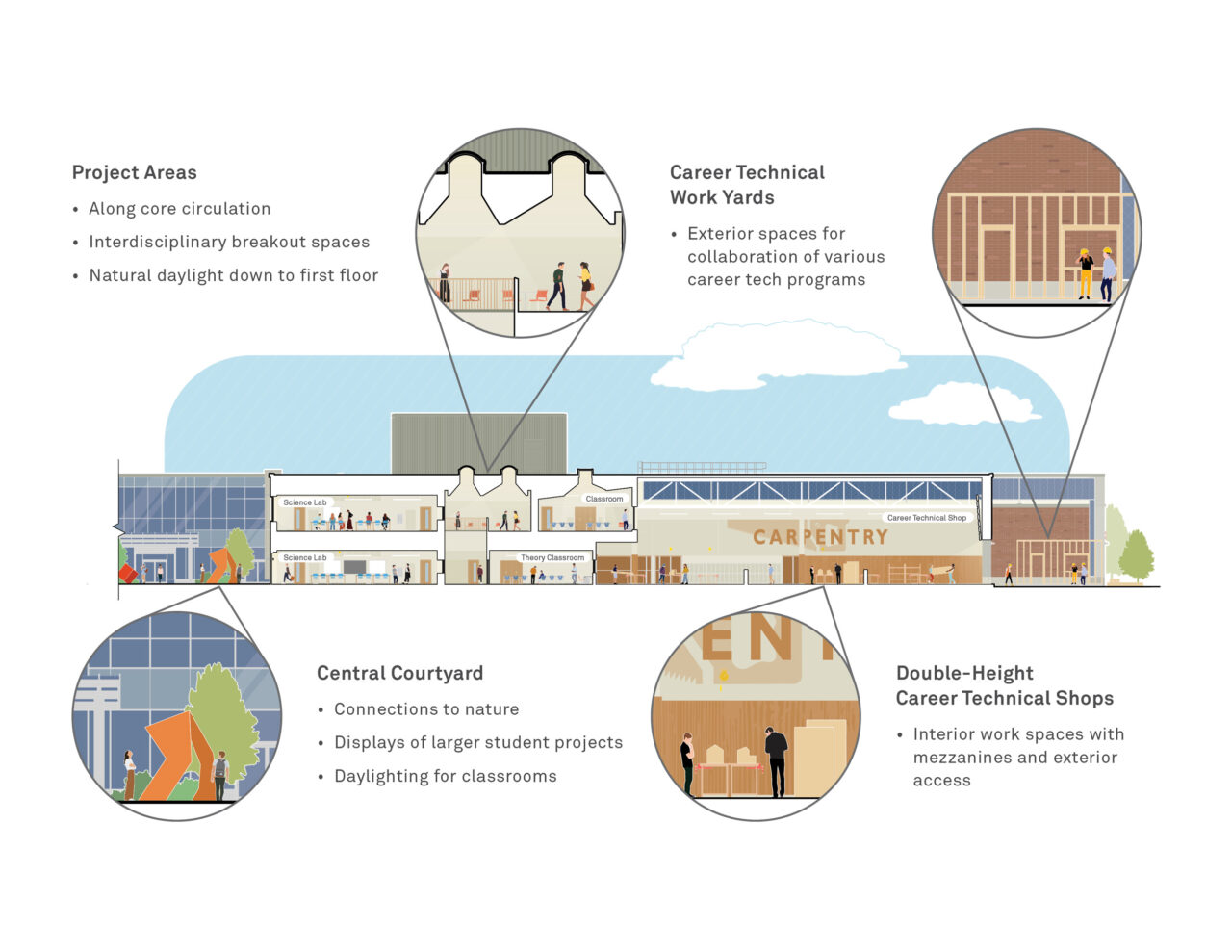

The HMFH design supports vocational education’s continued destigmatization. Bristol-Plymouth Regional Technical School’s culinary, cosmetology, graphics, and childcare programs are located on the public elevation of the forthcoming building’s south volume, and adjacent visitor parking, clear signage, and bold graphics boost the departments’ community visibility. Vocational classrooms are placed along the entire perimeter of the 400,000-square-foot courtyard building, with academic and vocational classrooms facing one another across a double-loaded corridor. Versatile project areas where, in Stanislaski’s words, “a science teacher could join a vocational class for a group project,” integrate lessons and their real-world applications. In addition, the new high school is configured around shared interiors that feature sculptural elements, stressing the value of craftsmanship and fostering a collective identity for more than 1,400 students.

Sustainability figures prominently in the character of Bristol-Plymouth Regional Technical School as well. HMFH has maximized daylight penetration in the building, which could also achieve Net Zero Energy should rooftop photovoltaics get funded. The project is also an MSBA pilot, in which the architects are researching nontoxic equivalents to unhealthy surface products using Declare, a platform that supports material content transparency.

Modeling a New Standard

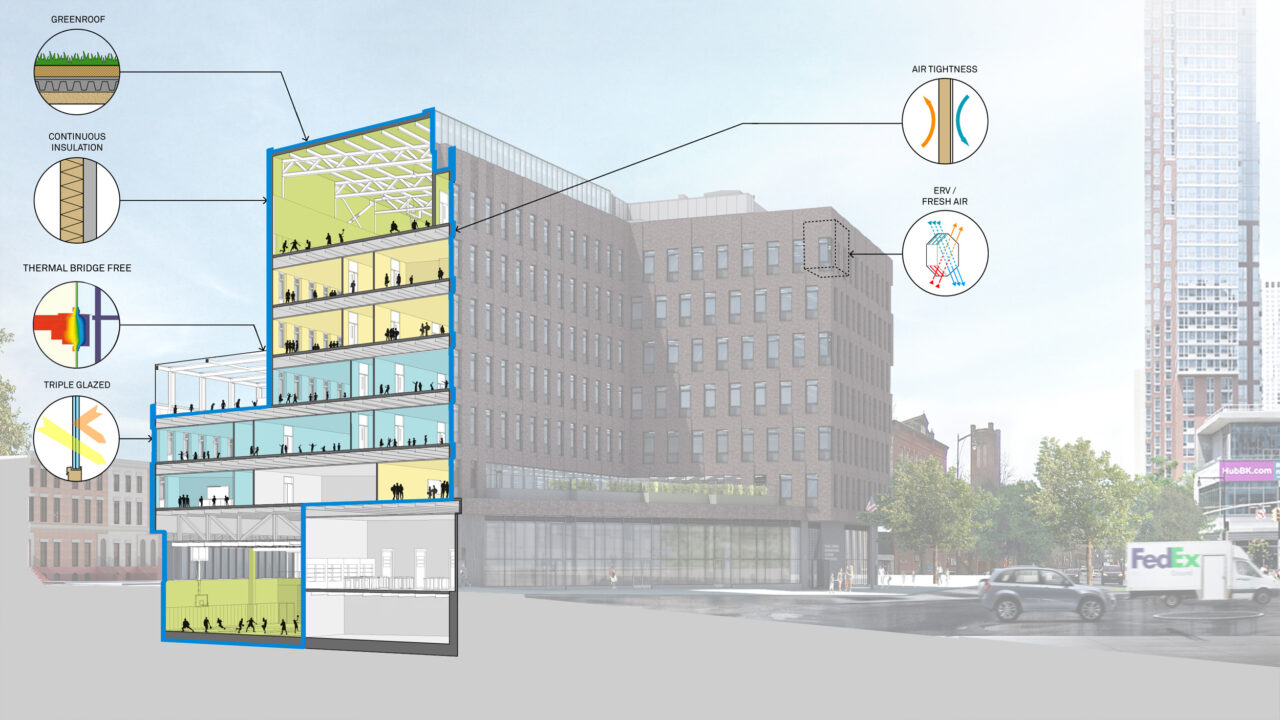

Downtown Brooklyn will accommodate more public school students now that the mixed-use Alloy Block—which includes an all-new primary school and a replacement facility for the Khalil Gibran International Academy, an Arabic language public high school—has begun its two-phase construction. The project will expand the capacity of the high school and update its facilities, sharing a cafeteria with the primary school. As its principal, Stephen Cassell, AIA, recalls, Architecture Research Office (ARO) had already begun designing the two facilities in 2016 when conversation turned to New York City Council’s new adoption of Local Law 31, which requires greater energy efficiency of public capital projects. The team decided to pursue Passive House certification; the two schools will be the first to be certified in the city. “We knew that with the law coming online, this would be a good opportunity to figure out a way to reduce energy use to the EUI requirement of 38 kBTU per square annually,” Cassell says. “The SCA and the design team thought this was a great opportunity to push for Passive House standards.” ARO project director Dominic Griffin, AIA, explains that, as a joint project of developer Alloy and the New York City Educational Construction Fund, “we were able to propose deviations to SCA standards to achieve Passive House.”

Griffin also notes that such deviations were few. “The envelope of a brick façade with punched windows that’s typical of SCA buildings should perform relatively well,” he explains. “It’s the lot-line conditions, abutting a tower or historic building, where you have to maintain envelope and insulation continuity to avoid a thermal bridge.” The architect explains that ARO and its collaborators resolved those transitions out of the public eye, whereas a high-performance HVAC system that employs refrigerant instead of forced air and triple-glazed windows that also acoustically dampen street noise will strike observers as delightful departures from the norm.

In response to the ongoing climate crisis, and adhering to local legislation, including NYC Local Law 31 of 2016, the SCA sought to modify its existing building standards to reduce energy usage in new schools. The SCA partnered with FXCollaborative, and the firm led a team of consultants to evaluate the existing standards and propose new energy-efficient, practical, and cost-effective alternatives.

This collaboration resulted in the creation of a Feasibility Study that found the potential for newly built schools to have 31% less energy use intensity and 40% less greenhouse gas emissions than the previous standards. The team achieved this by implementing solutions inspired by the Passive House Standard, such as envelope efficiency and energy recovery ventilation, and preparing for a renewable energy future through full building electrification with solar energy production.

The SCA has since adopted virtually all of FXCollaborative’s recommended energy conservation measures as standard.

“While we’re trying to push Passive House, we are all cognizant that the project has to be built incredibly well and last an incredibly long time,” Cassell says. “At the same time, its upkeep has to fit with how SCA building engineers run the physical plants within the budgets they have. This is sort of an experiment in applying the lessons of Passive House to New York’s complex construction environment, and we’re super-happy that SCA has embraced it.”

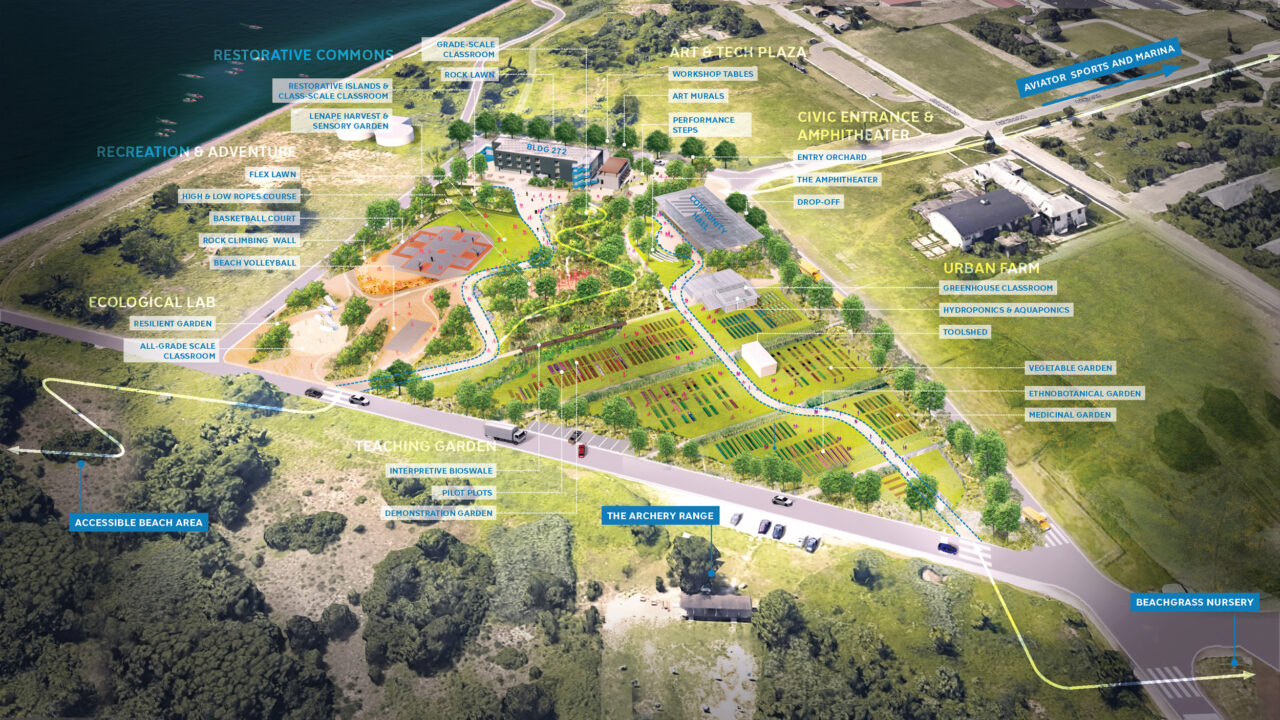

A more recently announced ARO project is the Launch School, a new high school campus planned for seven acres of the former Floyd Bennett airfield in Queens and slated for completion in 2026. Developed collaboratively with SCAPE, Colloqate, and the Launch School’s community and partner network, the campus will be organized around a series of connective outdoor hallways that knit together buildings and learning landscapes—and which embody a core curriculum whose pillars include anti-racism, climate action, sustainable food systems, environmental justice, and experiential learning. Currently, the Launch School operates from Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, home to many students who have been systematically excluded from opportunities leading to green jobs. At Floyd Bennett Field campus, students will engage directly with these issues through hands-on learning.

“In a digital age, our youth are hyper-exposed to some of the most pressing issues shaping our cities and communities—climate change, environmental racism, food insecurity, and more—while also being detached from hands-on solutions, civic participation, and workforce training in related careers,” says Alexis C. Landes, managing principal at SCAPE. “At every scale, micro to macro, the campus brings students into the process of transforming the land, building a next generation of leaders who understand the value of collective action and collaboration in a changing environment.”

DAVID SOKOL is a longtime New York-area design journalist who is now based in the Hudson Valley. His October 2022 book, Hamptons Modern (Monacelli), is a follow-up to 2018’s Hudson Modern. He also contributes regularly to Architectural Record and Dwell magazines.