In the social upheaval that followed the wake of George Floyd’s murder in the summer of 2020, the Gensler Research Institute established the Center for Research on Equity and the Built Environment. The center focuses on funding research addressing systemic racism, unconscious bias, and social justice, and one of its first published papers was the result of a Black Lives and Design grant for the research initiative, “Education and the BIPOC Experience: Amplifying Student Voices in New York City High Schools.” The report sought to include Black, Indigenous, (and) People of Color (BIPOC) students as stakeholders in the design process by considering the nuances of their experiences and by giving them a sense of agency in their built environments. While the group acknowledges that classroom and school design alone cannot eliminate systemic and structural disadvantages in the education system, the center continues to advocate for and learn from BIPOC student feedback. Gensler’s Margot Kleinman, AIA, who works primarily on the firm’s education projects, shares more about this initiative with Oculus Editor-in-Chief Jennifer Krichels.

Can you explain the genesis of the research and the methodology you used?

Gensler is really involved with the Architecture Construction Engineering (ACE) mentor program. We had a student mentee in the office one day who explained to one of my colleagues that he felt like our office was “mad bougie.” He said it felt like a place for people like my colleague and not for people like him, which was really hard for my colleague to hear. Further conversation led to starting this grant, as it was an applicable time to start looking into the BIPOC student ex-perience in their school spaces. We’ve been participating in the research for three years now.

First, we decided to deploy a survey. We used our connections through ACE to deploy it to 18 public schools in New York City. We workshopped the questions to make sure we were removing as much bias as possible from the way the questions were written. We made sure there were some open-ended questions, some multiple choice, some select-all. That way, we’d get a variety of responses. We had four sections to the survey, which were demographics, safety, belonging, and experience. We also asked students to compare two schools based on their physical appearance and share their impressions. The open-ended questions had a lot of insight since we were hearing the students’ direct words.

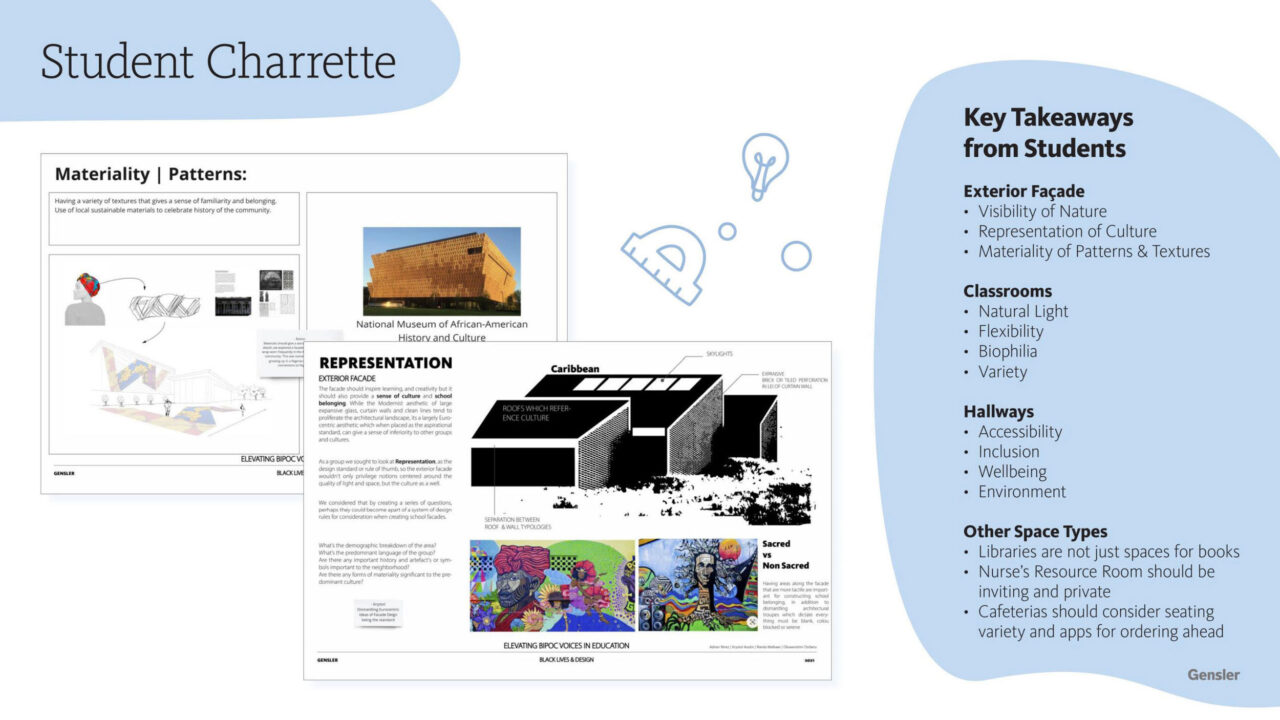

From the anonymous survey, we decided we needed to engage with students more directly. So we designed a two-day charrette that focused on working with our Gensler interns, who were all college students at the time. We had them reflect on their high school experiences and engage with different spaces within a school, focusing on their sense of safety and belonging—that’s always been what we fell back on talking about. After that, we decided to engage with students for even longer so we could develop more of an ongoing relationship with them, and be able to have more candid conversations. An opportunity arose for us to engage with Uncommon Schools, a charter school system in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. We developed a program where we worked with four of their high school seniors to select an education space they wanted to study and develop a design proposal for; it was an opportunity for us to introduce them to architecture for the first time, which was great for them. One of them went on to study architecture in college, which was an exciting surprise benefit of the program.

What kind of work has come out of the program?

We met with the students weekly over about six months and got to see their eyes open up as designers. We had candid conversations where we could dive in and have this relationship grow, so they felt comfortable speaking with us and having a safe space between us. From there, we held a second charrette. We also did an Education Leaders roundtable. So there have been a number of in-person and direct engagements since the survey.

We’re connected to the organization Schools that Can, and did a modified, three-week charrette, meaning we met with a different school once every three weeks to do a quick design challenge. On the side, I’m still working with Uncommon Schools, mentoring a high school senior over the last few months. Now, it’s less that same program and

more like spinoffs of it to continue engaging with students. So there’s still content to dig into from both the Education Leaders roundtables and some of the charrettes we’re still planning on sharing. We’re continuing to engage with students on project work as well.

Is there anything else that surprised you about working with students in the high school age group—about how they’re looking at problems in a new way?

I would say that though we may presume students feel some way about certain things they are experiencing now, we are not hearing what we expected. One question we initially asked in our survey was about physical safety measures in schools—we saw that most have metal detectors here in the city. People around my age didn’t always have metal detectors growing up, and when I go through a space that has a metal detector, I typically think, Why does this need to be here? Maybe it shouldn’t be here. But what we heard from the students was they’re happy they’re there. They know that once they go through the metal detector, they’re safe, and it’s just part of their entry experience. Same with the presence of security guards. We thought maybe they wouldn’t like having them there, or maybe there would be some debate over having them around, but most students felt they increased their sense of safety as well. That was interesting; things we thought might have been a problem aren’t always. And even windows are a big conversation: some students didn’t want to be seen from the street, some students think it’s distracting, and others love the daylight.

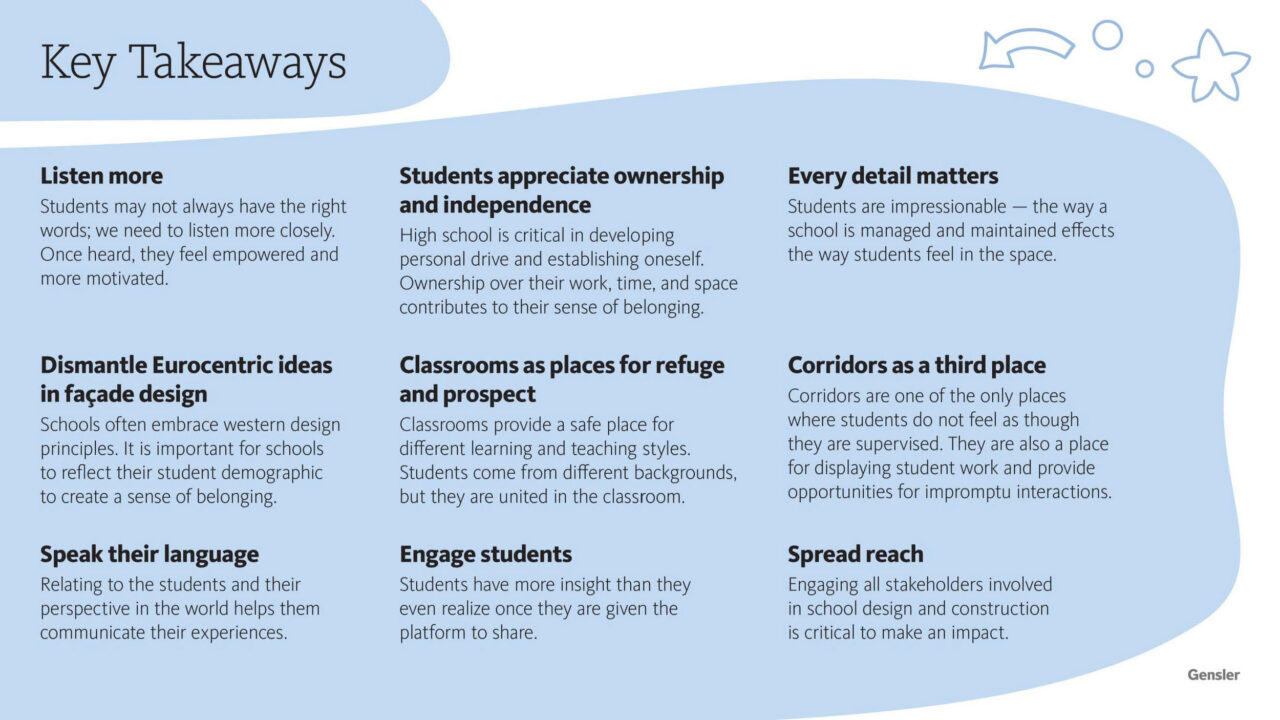

So, they always have something interesting to say, but sometimes you go into it thinking you know what they’re gonna say, and you just don’t. So we always em-phasize listening and putting aside what we think we know, because they’ll say something different.

Are there additional areas where you can see more research taking place in the coming years, or other areas you’d like to explore?

This research started in order to elevate the underrepresented student voice. What we found in the beginning was that, it’s not that research about how students feel in spaces has never been done—it’s that researchers are typically speaking to white students. So this is about, how are we using our platform? How are we using our position as architects to engage with those students whose voices aren’t typically represented and heard? Especially in an environment like New York City, or in a school that is mostly not white students, but you’re basing your research off a white student experience—that doesn’t add up.

The other point is that the student experience is always changing. So what students are experiencing in school now is different from what I experienced and what you experienced. It’s constantly changing, and it’s changing even faster these days. So it’s important to continue to engage with them. Like the research we did in the beginning of 2020—students might feel different now, and they might feel different three years from now. So it’s really the understanding that it’s not, “We learned this one time, and it’s applicable forever,” but to make sure it’s continued engagement and listening.

Some of Margot Kleinman’s favorite podcast episodes are:

“Three Miles” episode of This American Life, March 13, 2015

Nice White Parents podcast series by Serial Productions and The New York Times