The housing shortage is what planners call a wicked problem—difficult to solve because of social complexity, unclear requirements, and indeterminate metrics. Though Mayor Eric Adams and other officials continually address it through blueprints and programs, homelessness in New York City “has reached the highest levels since the Great Depression,” according to the Coalition for the Homeless. Common Ground/Community Solutions Founder Rosanne Haggerty, a 2001 MacArthur Fellow for her achievements in combating homelessness, calls it “a slow-moving emergency” requiring “the same kind of command-center intention and structure and commitment” that would be applied to “the aftermath of a hurricane.”

If the lack of housing within reach of New Yorkers outside the 1% resembles a Superstorm Sandy without end, what should one make of the language denoting the housing itself? Linguists recognize the concept of marked-ness: in a binary pair of terms, the one carrying an extra mark is the subordinate or disparaged one (e.g., healthy/unhealthy; honest/dishonest; privileged/underprivileged). Affordable housing is a marked term, implying that unaffordable housing is actually the norm. This is both absurd and, in the housing markets of New York and many other cities, all too prevalent. Could this key term and its implicit conceptual framework be part of the problem?

STIGMATA VISIBLE AND INVISIBLE

“The word affordable is more of a political and economic construct, which is about rental subsidies more than anything else,” says Jack Esterson, AIA, principal at Think!, which has designed rentals and condos in the affordable, supportive, and market-rate sectors. He finds that the cost of building is similar regardless of the “affordability” label (soaring land costs are a different matter). Yet this term “in New York, especially in underserved communities, is met with a certain derision,” mixing class prejudice with stereo-types of bare-bones detailing, an image Think! and other firms are striving to render obsolete through sophisticated design resistant to penny-pinching imperatives.

Esterson’s colleague Martin Kapell, AIA, notes “there was a time when people doing that work were afraid that if their buildings looked good, they would be accused of spending frivolously and inappropriately, so the buildings all looked the same: jumbo brick with maybe a band of black brick, small windows, a lot of exterior insulation finishing systems, and through-the-wall air conditioners.” Agencies prioritizing ratios of units built to dollars spent resisted better design ideas. “Even though they were perfectly justifiable programmatically and financially, it seemed like a frill,” Esterson recalls. “It was an inch too much, a little too much glass, even though it meant a tremendous amount to our non-profit affordable clients and the people who lived in these buildings.”

Institute for Public Architecture Founder Jonathan Kirschenfeld, AIA, identifies six- by 12-inch brick made of low-grade clay as “the one big tell,” along with precast concrete lintels and sills. Improving on this look is not unduly costly, notes Kirschenfeld, who prefers durable Endicott iron-spot brick from Nebraska in the 12-inch Norman size, which “proportion-wise is closest to the Roman” brick used at Carnegie Hall, “even though it is less expensive than the modular.” His firm’s buildings in the affordable and supportive sectors bear this distinctive visual signature. When asked, “Where did you get the extra money to do your building?” Kirschenfeld typically replies, “We use the same budget everybody uses; we know how to use our budget.” He notes, “My dictum has always been: If it looks like affordable housing, you haven’t done your job.”

In real estate and politics, affordable housing has a quantitative definition (consuming ≥ 30% of household income, with local subsidy criteria based on percentages of area median income). “The term ‘affordable housing’ has been around since the 1980s, not before,“ says architect/historian Susanne Schindler of ETH Zürich and MIT. “It was about low- or moderate- or middle-income housing, and there was always the association with public or subsidized housing.” She adds, “Talking about subsidized housing is totally wrong because the mortgage-interest deduction is the largest subsidy given to housing, which has nothing to do with a needs-based subsidy. Anybody who has a mortgage can claim it. So, basically, the biggest subsidy is given to the people who least need it.”

One effect of the tax system’s bias favoring homeowners over renters is that when a privately owned home is a middle-class family’s chief wealth-building instrument, concern over property values makes them single-issue voters who skew Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) on residential policies. AIA New York Chapter Housing Committee Co-chair Peter Bafitis, AIA, of RKTB Architects, cites New York State’s failure to legalize accessory dwelling units (ADUs), “an immediate way of increasing the housing supply without really building anything,” as a case in point. ADUs have been legalized in California, New Hampshire, Minneapolis, and other jurisdictions. “New York should have been leading the charge on that and hasn’t,” Bafitis says. Governor Kathy Hochul “demurred because of the election, because it’s a hot-button issue among the suburbs.”

The mortgage subsidy is economically regressive—a 2019 Brookings op-ed in the Wall Street Journal noted that, “In 2018 almost 17% of the benefits will go to the top 1% of households, and 80% of the benefits will go to households in the top 20% of the income distribution”—yet politically popular, perennially resisting congressional austerity axes even though economists have argued it actually reduces homeownership by pushing up house prices. Though affordable-housing subsidies can carry the stigma of redistribution benefiting the poor, the mortgage subsidy dramatically outweighs them (six times the federal aid to renters, according to one 2018 analysis). Kirschenfeld questions, “Why should we be depending on flipping our housing as our economic lifesaver” instead of having “appropriate wages that allow us to build a nest egg?” He suggests a simple policy tweak: “Renters should be given a tax break, just like homeowners.”

A COMMODIFIED HUMAN RIGHT

Language that steers priorities and shapes assumptions is only part of the story. “Affordable housing” masks confusion over just what housing constitutes: a right that communities and civilizations guarantee to all people, or an economic entity to be bought, sold, hoarded, privatized, financialized, and withdrawn through eviction. It can be either one; the contexts affecting which sense prevails are, inevitably, uncomfortably political.

The United Nations’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, with the U.S. among its original signatories in 1948, includes a right to adequate housing, yet a 1972 Supreme Court decision, Lindsey v. Normet, denied it the status of a constitutional right. Bafitis notes that “what created public housing in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s was an enormous federal investment in it, and that spigot was turned off in the ’70s and ’80s, and it’s been languishing ever since.” Since efforts to provide housing broadly through direct federal subsidies ended, replaced by a patchwork of public programs aimed at mobilizing private markets, commentators across political spectra agree that current arrangements have not yielded enough construction. From the 2008 recession through the pandemic, Bafitis adds, housing construction has been particularly weak, leading to “an unaffordability crisis across middle America,” becoming increasingly visible in the mainstream.

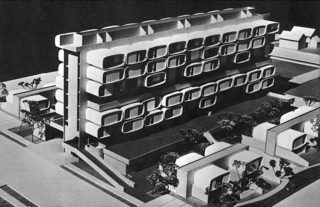

James McCullar, FAIA, recipient of the AIA’s 2019 Thomas Jefferson Award for Public Architecture, views the evolution of New York’s public housing as a narrative of initial promise declining into mismanagement, exacerbated by local discontinuities. “When I first started doing work in the city, even in the 1970s,” he says, “the public housing developments were oases of calm and landscape and maintenance. The areas around them were dilapidated for abandonment and lack of maintenance; those that were occupied were in poor condition. But as time went on, the reverse happened. The best housing is integrated into its community,” and Corbusian towers in parks usually stood apart. (Stuyvesant Town strikes him as an exception, maintaining working-class demographics rather than concentrating the most underprivileged.)

McCullar cites excessive focus on cost as one reason New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) buildings have acquired a bad image. In the late 1970s his firm rehabilitated an abandoned South Bronx tenement, 1660 Andrews Avenue; his Art Deco design won an AIANY design award and earned praise from the Times. McCullar recalls, “The deputy manager of NYCHA, who was a hardcore affordable-housing guy, a cheap-housing guy, said to me, ‘My God, you got a design award; you must have spent too much money on this. You have to understand that public housing is the minimum expense.’ He actually gave us a hard time about that.”

The scale and structure of NYCHA, McCullar suggests, militate against efficient management as well as aesthetics and amenities, and he speculates that smaller organizations would outperform New York’s large regulatory apparatus. He points to Houston’s relative successes, in a setting lacking both rent regulation and government-sponsored housing, but featuring “varying degrees of affordability,” along with a housing-first policy and a high degree of social-service coordination through its Coalition for the Homeless. He also cites Singapore, which combines ample publicly built housing with a mandatory 401K-like program allowing residents to apply their savings to housing purchases, attaining a very low citywide rate of homelessness.

There is no shortage of arguments that privatization and deregulation would align incentives for more new construction. Others have less confidence that markets can respond appropriately. “My counter to those who say, ‘Capitalism with free reign would solve these problems,’” says Esterson, is, “You have to look at the record. It hasn’t.” After the federal commitment to public housing collapsed during the Nixon and Reagan administrations, “capitalists had the chance to fix it; it did not happen, and homelessness went through the roof. The free market is having a very difficult time right now building middle-income housing, which is another crisis in New York. Middle-income families have a really hard time; rents are crazy, they’re not wealthy enough to afford good housing, and yet they’re not poor enough to qualify for low-income housing, so they are stuck in the middle, and the free market has not been kind to them.”

LTERNATIVE MECHANISMS, ABROAD AND HERE

Schindler points to “the so-called third way of non-profit housing,” separate from the restrictions of public-sector housing and the instabilities of markets, as a variant with a promising track record overseas. Zürich has a century-long tradition of non-profit housing, including cooperatives that charge a “cost rent” based on “just what it costs to operate this housing, to put away funds for capital improvements in the future,” without either income caps or a primary motive to appreciate in market value and generate wealth. The return on residents’ investment is paid not in cash but in a “use value dividend,” including a lifelong right to stay and participate in community governance. Cooperative organizations control about 9% of Zürich’s buildable land (preserving it from speculation and reducing gentrification) and 18% of its housing stock. Schindler has studied the possibility of similar systems in Boston, which has a stronger history of co-ops than most American cities, though institutional support would be essential to scale up the model.

For Zürich’s model to translate to the U.S., she acknowledges, it would have to overcome the association between housing and personal wealth. “Housing as an asset,” she observes, “this whole American dream of owning something is so central not just to people’s imaginations, but to how people save for retirement.” That linkage is a solution to some and a deeply entrenched problem for others, entangled with the history of racial bias. “Those who have owned housing for 100 years have been able to pass it down through generations, and that has created this enormous discrepancy between Black and white households, because Black households were explicitly excluded from homeownership.” Racial redlining is one of many reasons why American housing history has suffered from the tension between “two contradictory policy goals: building wealth through housing, and affordability. Those two things basically cancel each other out.”

In London, a localized public-sector model offers encouraging case studies. Paul Karakusevic, founding partner of Karakusevic Carson Architects, has worked with 15 of London’s 32 borough councils on projects that have redefined council estates as dignified, well-planned communities reflecting residents’ ideas and desires, after a period when social housing connoted top-down design and underfunded decrepitude. “Approximately 15 years ago,” he says, “Gordon Brown, Labour prime minister, brought back lawmaking to allow for the local government and local councils to invest in the housing stock and in building new, truly affordable housing for local residents. That was the seismic moment in the post-neoliberal era. By allowing the public sector to borrow again to build fabulous, solid affordable housing, local authorities reentered the housing sector, which had been frozen out for circa 30 years.” Direct management by the democratically elected councils “maximizes the value capture for the public sector. It means they’re in control—their residents are closer to the action and decision-making.”

It is a painstaking yet productive process, he notes: “We will meet our residents on a project 30, 40, 50, 100 times from the beginning of the process to the detailed drawings, the fit-out drawings of the flats, and the design of the lobbies.” Meetings address not just master plans at the outset but “kitchen finishes and tiles in the bathroom,” deepening trust that years of neglect had eroded. Many of these projects are mid-rise blocks, either reconditioned or replaced by new buildings, three to seven miles outside central London amid parkland and other amenities, typically with a density of 150 to 300 dwellings per two-and-a-half acres. Some residents are comfortable in larger towers, 14 to 25 stories high, enjoying views, quiet, and air quality, provided the lifts and other details are maintained. Tellingly, Karakusevic’s book Public Housing Works (Lund Humphries, 2021) includes a section called “Dwellings, Not Units,” reflecting a conscious choice of a human-centered term.

Karakusevic shared his experiences with NYCHA officials and New York-based architects at AIANY’s “Public Housing, Practice, and Design” symposium last June. He views NYCHA as a unique city asset, “one of the ultimate housing and architectural challenges, probably, in the world,” with “incredible opportunities of extension, deep refurbishment, façade improvements, thermal upgrading, and ground-floor improvements. The functionality and the retention of that stock is absolutely key to allow the city to function as well as possible for the next 200 years.” Believing deeply that “public housing should be city infrastructure,” he is encouraged by the city’s new Public Housing Preservation Trust as a mechanism for long-term bond sales to support necessary renovation, construction, and preservation from disruptive speculation. Citing economist Mariana Mazzucato’s work on varieties of valuation, he says, “When the city stays in control of its assets, it is definitely much more than financial—it is social value.”

Perhaps the most intriguing third-way institutions recognizing social value over marketable value are community land trusts (CLTs), separating land ownership from building or residence ownership. A CLT “can freeze the land value, which is typically what drives up the value of the home,” Schindler says. “It’s the location, the land, the real estate—not the structure itself—and that’s very similar to the Swiss model.” CUNY urban planner Cassim Shepard’s recent Places article on CLTs finds 17 of them in the city (including the Mott Haven/Port Morris Land Stewards) and nearly 300 nationwide, in 47 states and the District of Columbia.

Challenges for the CLT model, Schindler says, include getting traction with funding institutions, developing technical and managerial expertise, defining what communities they represent, and acquiring land. Government could encourage CLTs by establishing mortgage insurance, assuring banks that loans to a CLT are secure, and allocating tax-fore-closed properties to them, subject to appropriate oversight. Although some CLTs grew from autonomous grassroots organizations resistant to government, she says, “It’s an illusion to think you can get anywhere by completely separating yourself from the market or the state. You’re always implicated in this world, and the long-term affordability is assured by the fact that the land can no longer be speculated with.”

Kirschenfeld looks nostalgically at the period when New Yorkers “were the innovators, not just for housing but for who pays for housing. These were labor unions; these were pension funds; the U.S. government was in the housing business. We’ve lost a lot in making every project in New York a public-private partnership, because that’s an abdication of responsibility, aside from the fact that housing should be a right.” He energetically advocates CLTs as innovators in the next evolutionary stage of housing, and from his work with the Mott Haven CLT, he recalls a representative of the city’s Health and Hospitals system, which owned a building in the CLT’s catchment area, implicitly linking those two rights.“Health and Hospitals came out with a very, very interesting nugget,” Kirschenfeld recalls. “They said if there was anything we could prescribe to our patients, it would be housing.” A stable residence is a well-known contributor to health, particularly for persons who have endured a period of homelessness. There is an intuitive logic to reframing residences as a component of public health infrastructure, calling for the expertise of not-for-profits in health and adjacent fields.

Nadine Maleh, housing systems director at Community Solutions, notes the implications of the components of social support networks, in both terminology and substance. “We have a homeless response system: think about that,” she says. “We don’t have a housing system. We have a healthcare system; we talk about healthcare as the benefit, like you’re going in for preventive care, you’re going in to be healthy. It’s not like we have a ‘sick care’ or a ‘sick system.’” Noting that everyone outside the “1% who don’t need mortgages” benefits from various social institutions (e.g., financial, medical, judicial), Maleh calls attention to how they overlap in ways rarely perceived by people who have never fallen through the gaps. While working in the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice several years ago, she once voluntarily spent the night at Bellevue Hospital during a code-blue night, when overnight temperatures are below freezing, observing intake procedures. About 90% of the men she encountered had come from Rikers Island. Just as public health specialists understand that prevention is more effective than responding to medical problems after they’ve become urgent, institutions operating on the adjacent fronts of housing, criminal justice, and mental health perform better in a preventive than a reactive mode, and better when coordinated than when siloed.

Maleh’s colleague Rosanne Haggerty recalls that Jane Jacobs habitually accentuated the positive. “Death and Life and other books that resonate in terms of telling us what we love about cities and our homes don’t talk about income,” she says. Instead, the focus is on “belonging, agency, relationship to an environment that makes us feel a sense of familiarity and security.” The useful questions about reinvigorated buildings, she says, aren’t, “What are the incomes of the people who happen to live there?” They are, “Are they well-designed? Are they thoughtful in the way they operate in their context? Are they welcoming, and is there some accountability? If there’s a problem, will someone show up? What kind of community do we want, and what’s going to make it feel that way? How do we include everyone? How do we start with the end state in mind: a place where nobody’s homeless, where no one’s rent-burdened, where the buildings are safe, where people feel a sense of connection and belonging? That has nothing to do with economics.”

Bill Millard (“Let’s Just Call It Housing”) contributes regularly to Oculus, the Architect’s Newspaper, Metals in Construction, Annals of Emergency Medicine, and other publications. His book The Vertical and Horizontal Americas, assisted by a Graham Foundation grant, moves glacially forward.