Operation Breakthrough (OB), the most comprehensive housing program of the Civil Rights era, had an incredibly short policy shelf life and quickly disappeared from public view and discussion. Who created OB, and why did its nine experimental communities have such a limited impact on the housing market, federal housing policy, and historical memory? Are there lessons from OB that might be applicable to today’s housing market, as resources are invested in 3D printed houses, mini-houses, the adaptive reuse of shipping containers, and other ideas?

ROMNEY’S SIGNATURE PROGRAM

George Romney announced OB in May 1969, four months after joining President Richard Nixon’s cabinet as secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Romney advocated a systems analyst approach to the production of housing for low- and middle-income markets. His goal was to remove the obstacles preventing the U.S. from utilizing technological innovation to increase housing production and stabilize costs. Romney recruited Harold B. Finger, a systems analyst for the National Air and Space Administration (NASA), to serve as assistant secretary for research and technology and oversee OB.

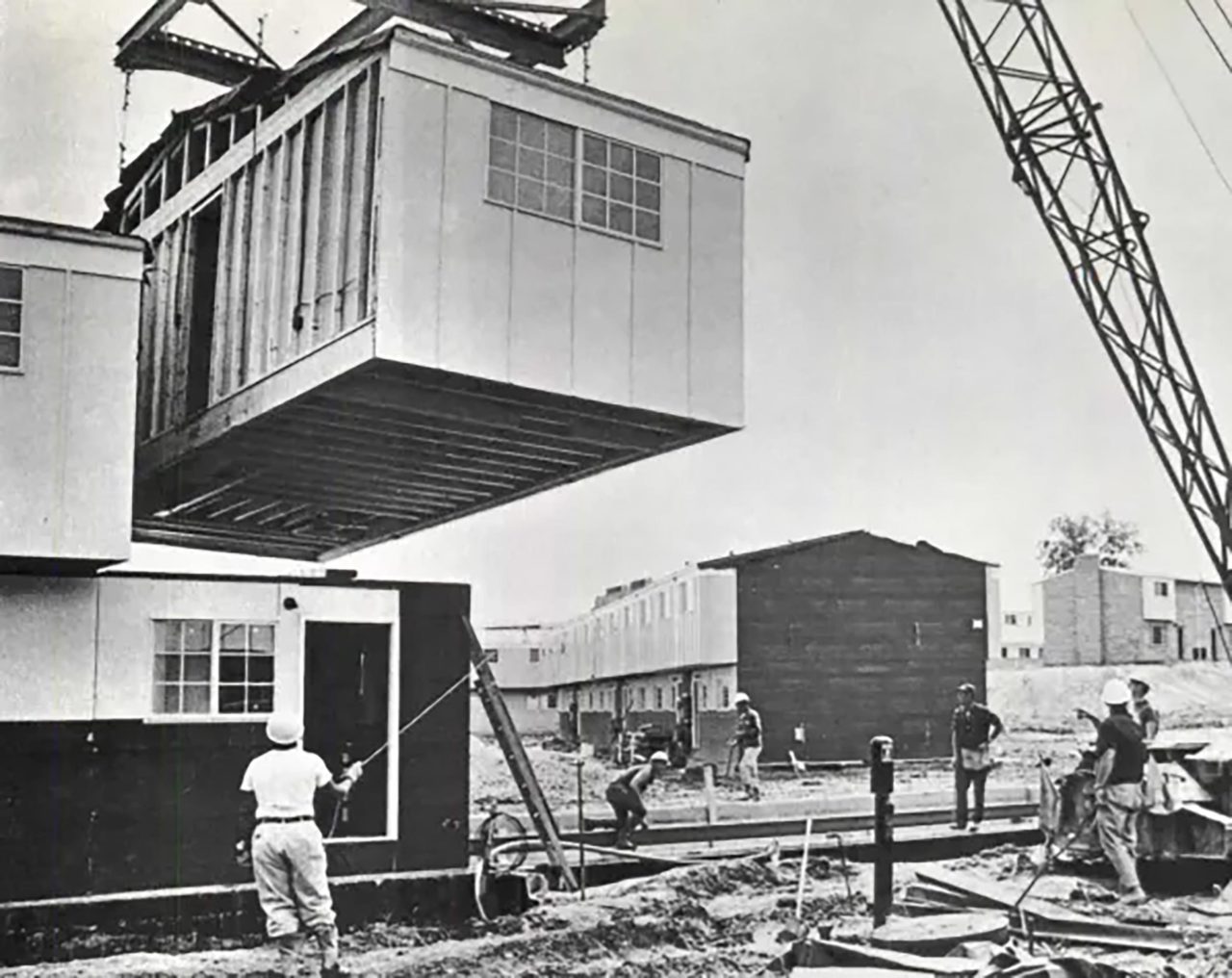

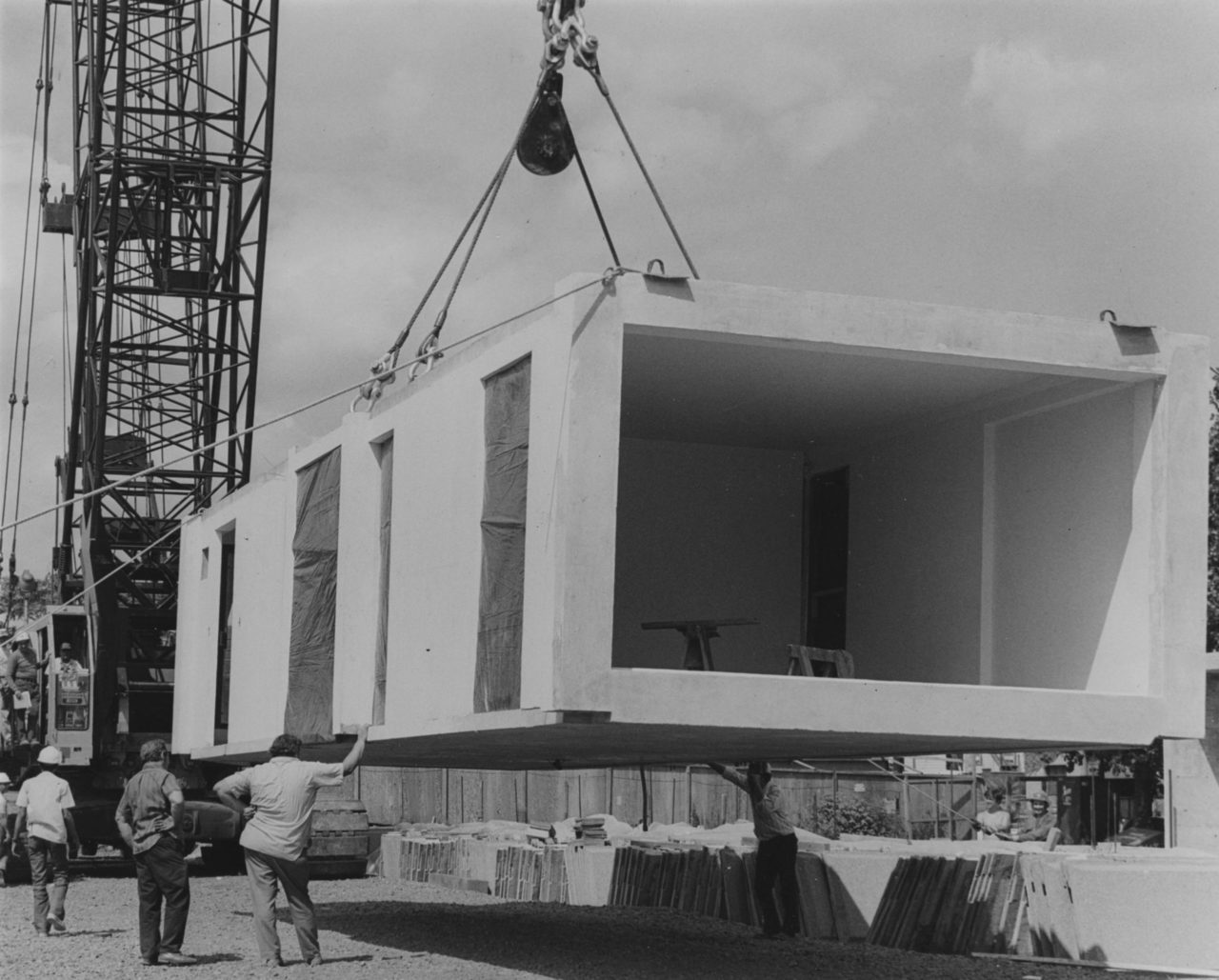

OB’s Phase I began when HUD invited housing manufacturers, architects, engineers, and designers to submit designs for different types of single-family and multifamily factory-built housing, and compete for a grant from HUD’s $15 million research and technology budget. During Phase II, the manufacturers with the most promising designs—the winners of the Phase I competition—would work with a private developer to build an assigned number of dwellings at one or more of 11 prototype communities nationwide.

The goal of Phase III was volume production. Romney planned to break new ground in federal housing policy by introducing a system of market assembly not unlike the healthcare insurance “exchanges” created during the Obama Administration. Market aggregation specialists working at state and regional levels would help publicly and privately funded developers with similar housing needs keep their building costs to a minimum by jointly negotiating with one or more manufacturers. Market assembly would help new and established firms reach economies of scale and stabilize their prices. Organized labor had proposed market aggregation during World War II, and it had been temporarily implemented during the postwar veterans’ housing emergency, with the support of President Harry S. Truman.

Romney created OB a year after the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and his successful campaign as the Republican Governor of Michigan to secure passage of the state’s first fair housing law. As a result, it was much more than an effort to industrialize house building. Romney quietly accepted the politically perilous responsibility of leading the nation into the uncharted territory of equal opportunity housing. OB’s prototype communities would show the nation—and the world—what a post-Jim Crow residential neighborhood could and should look like. Federally subsidized development would require private sector contractors participating in federal housing subsidy programs to train and hire minorities from the local area, with the ultimate goal of attaining the benefits of union membership. Opportunities for minority contracting and investment would emerge. Romney expected OB to buttress his effort to transform the four-year-old, cabinet-level department into a technologically savvy, research-oriented source of expertise on national economic development and urban policy that had outgrown its New Deal, social work origins. The rebranding of HUD would result in Congressional budgetary allocations that more closely approximated the department’s needs and legislative and programmatic obligations.

ROOTED IN THE GREAT SOCIETY PROGRAM

Romney found a mandate for his goal of fundamentally altering low- and middle-income housing production in the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, one of the signature bills of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s outgoing administration. Dubbed the “Magna Carta of housing,” it established the goal of 26 million units of new or rehabilitated units of housing in a decade. The purpose of the law’s Section 108, “New Technologies in the Development of Housing for Lower Income Families,” was to “encourage the use of new housing technologies” and “large-scale experimentation in the use of such technologies.”

It authorized the HUD secretary to approve up to five public or private research demonstration projects featuring promising new technologies that would be tested on at least 1,000 units a year for five years, which would presumably provide an adequate test of the hypothesis. The target figure of 5,000 dwellings was an estimate for the production needed to reach an economy of scale for the manufacture of detached, single-family dwellings. Backers of Section 108 hoped the experimental dwellings would serve as models for housing provided under the public housing, urban renewal, Model Cities, or New Communities programs.

Romney hitched OB’s wagon to what was arguably the 1968 law’s most liberal and controversial provision: mortgage interest subsidies. He expected low- and middle-income households that qualified for the mortgage interest subsidy program, authorized under the National Housing Act’s Section 235, to constitute the bulk of the customers for dwellings built by OB participants. Residential developers that purchased OB housing could seek mortgage interest subsidy payments under the Section 236 program.

Romney’s approach to the legislative directives contained in the 1968 housing law reinforced the Nixon Administration’s program of New Federalism. He increased federal reliance on state government for the building, marketing, and management of low- and middle-income housing by the private sector. HUD encouraged the small firms that had historically built, financed, and marketed the bulk of U.S. homes to join consortia with large multinational corporations when seeking an OB grant from HUD. Grant recipients were to produce a prototype of at least one kind of commonly produced dwelling, including mid-rise, multiunit apartments; garden apartments; semi-detached town houses; and detached dwellings. Romney wanted OB’s prototype houses to become “so well-known and popular that public and private groups will be eager to become involved in their utilization.”

PLANNING THE PROTOTYPE COMMUNITIES

The department planned to test the quality of the design and construction of the dwellings designed and constructed by 26 housing systems providers at 11 regional prototype communities in Jersey City, NJ; Macon, GA; Memphis; St. Louis; Seattle; King County, WA; Sacramento, CA; Indianapolis; Kalamazoo, MI; New Castle County, DE; and Clear Lake in Houston. Working through a private sector developer, HUD expected to sell or lease the prototype dwellings with the understanding that federal housing officials would continue to monitor their durability, energy consumption, and overall performance. One observer recalled that OB was “heralded as the Cape Canaveral of the housing industry,” a reference to the Florida space center.

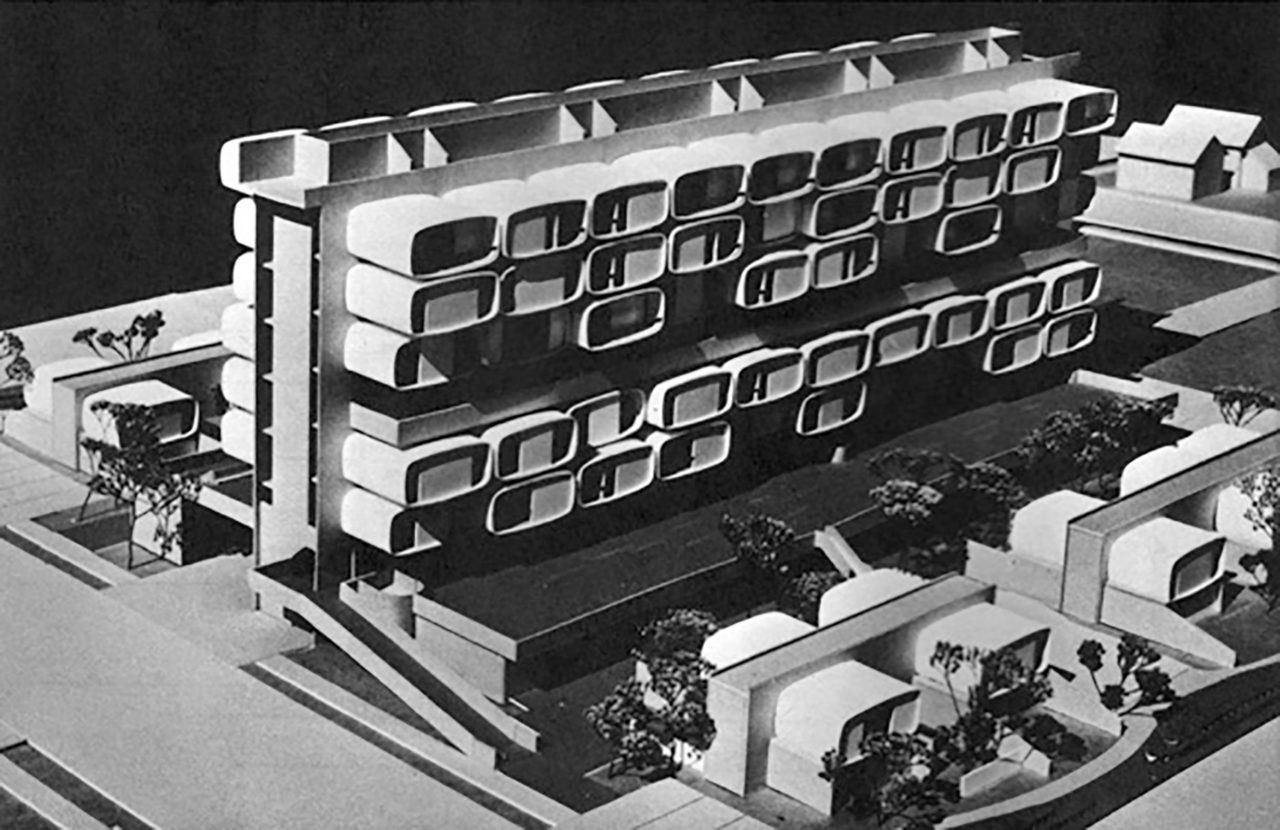

HUD required local governing bodies to vote to confirm their willingness to host a prototype community and agree to grant exemptions from local or regional plans, zoning laws, and building codes. The Operation Breakthrough cities were neither required nor discouraged from conducting hearings or providing a period for public comment on participation in OB. HUD selected a local or regional private developer to take ownership of each site and oversee its construction. The department also contracted a “notable” planning firm for each prototype community. The planners were responsible to “coordinate the plans of housing producers, integrating three to seven different brands and types of housing, including a combination of single-family homes, town houses, garden apartments, and mid-rise and high-rise apartment towers” into a coherent plan. The site plan would link the new community to the surrounding neighborhood and rectify the “injustices of top-down planning” that had physically isolated publicly subsidized housing in the past.

The planners’ goal was to “achieve economies and innovation in layout of roads, utilities, and services” and bring about the “harmonious linking of the given site with the surrounding community.” Their site plan would result in “a harmonious mix of housing types, family income levels, and lifestyles.” Most sites would feature four or five different housing systems. Sacramento’s prototype community presented its planners—Wurster, Bernardi and Emmons Inc.—with the challenge of seven different housing systems.

THE PROMISE OF A NEW LIFESTYLE

The two urban projects—Summit Plaza in Jersey City and Edison Park in Memphis—featured mid-rise apartment buildings, a community center, an outdoor recreation area, resident and guest parking, and pedestrian walkways. The former was located a short distance away from public transportation links to Manhattan; the latter was adjacent to a growing medical center.

Seven prototype communities were located in outlying urban or suburban areas where accessible housing was scarce. Planned Unit Development (PUD), a planning approach then gaining popularity, clustered dwelling units together, allowing for open space and the separation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic. Park Lafayette in Indianapolis marketed itself as a “new type of community,” where prospective residents would benefit from “dramatic new building technologies never before available to bring down the cost of ‘living it up.’” Sacramento’s Greenfair offered “a new and innovative concept” that supported a “whole new way of living.” Its sales flyer featured drawings of racial and ethnic minorities, families with children, and the elderly harmoniously enjoying “Leisure time Living” in an “inside the city” location. New Horizon Village, Kalamazoo’s prototype, called itself “Tomorrow’s Family Community…For Today’s Living!” at a time when fixed class and color lines divided the city’s neighborhoods. OB would help the “urban poor” get “out of the inner city and live closer to job opportunities as plants and offices spring up in outlying areas,” a news weekly predicted.

BREAKING THROUGH OBSTACLES

Romney pursued breakthroughs in the design, construction, and marketing of manufactured housing, while tackling other persistent problems facing the manufactured housing industry. Delegates to the meeting of the American Federation of Labor’s Building Council booed him at a May 1969 meeting for criticizing the union for its unwillingness to accommodate its work rules to technological change. Help arrived from an unexpected source organized labor and civil rights activist—Walter Reuther—at a time when the United Automobile Workers Union was cutting its historic ties with the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). In June 1969 Reuther told the Detroit News that trade unions had “more to gain than anyone else in America” from the rise of industrialized housing production and “ought to be leading the fight.” The industrial building systems would not take work away from the trade unions, he explained, but ultimately give them “more work, more membership, and year-round employment.”

On June 3, days after Reuther’s comments were published, the AFL-allied Detroit Building Trades Council announced plans to organize workers employed in industrialized housing plants. The New York Times called the move “history-making.” Shortly after, the 900,000 members signed a precedent-setting national agreement with the Stirling Homex Corporation to cover its factory assembly and on-site erection work. The Stirling Homex agreement precipitated what one builder called “something of a revolution” in labor relations because, up until that time, the craft unions had “insisted jealously and militantly” that all work had to be performed on-site by union members. The creation of an 11-week, 485-hour training program for unemployed minority construction workers co-sponsored by the National Urban League suggested that the United Brotherhood of Carpenters & Joiners had begun to accommodate itself to economic, political, and social change.

HUD issued guidelines in 1969 to assist OB’s contractors in the “planning, programming, and implementing of the ‘people-related’ elements,” of their work, including the “utilization of minority and locally-owned business concerns” and “manpower training of minority and indigenous residents of the areas.” Until Assistant Secretary for Equal Opportunity Samuel J. Simmons and his staff acted to correct the problem, HUD had no guidelines that stated in detail what the contractors should do in order to comply.

In 1972, OB Director Arthur S. Newburg reported to the National Association of Minority Contractors that HUD’s guidelines for “hiring, entrepreneurship opportunities, and housing went beyond basic statutes and executive orders.” HUD listened to minority contractors about problems they had encountered in the past, and adjusted the bidding procedure to function in a more flexible manner. Newburg reported that “bonding problems were dealt with head-on,” and OB staff offered “consistent direction to contractors” to help them learn how to fulfill their “equal opportunity responsibilities.” The major task of building homes required that minority firms and workers were involved in residential development at every level. “That,” Newburg said, “is what breakthrough is all about.”

Operation Breakthrough acknowledged that differences in local building codes and building regulations were a major impediment for housing manufacturers.

OB acknowledged that differences in local building codes and building regulations were a major impediment for housing manufacturers, who wanted state governments to replace local building codes with state laws establishing performance standards for manufactured housing. Romney observed that when OB started, “not a single state had a uniform building code that overrode local codes.” By late 1971, 20 states had uniform codes, and HUD was now “moving on to a higher plane with interstate agreements and reciprocity,” he said. OB staff also addressed disputes involving the shipping of sectional houses and building modules and panels across state lines, and encouraged rail-road and trucking companies to negotiate more favorable shipping rates with housing manufacturers.

Romney looked to another path-breaking provision of the Housing Act of 1968 to help him with the thorny issue of financing the sale of the prototype dwellings. He turned to the National Housing Partnerships Corporation (NHPC), the public-private corporation authorized under the bill to help raise private capital for the construction of low- and middle-income housing. Although corporate leaders proved to be more reluctant to financially support the venture than Congress anticipated, the NHPC provided the financing possible for three of the prototype communities to offer low- and middle-income householders the opportunity to become cooperative homeowners.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE OB COMMUNITIES?

Critics called OB a failure even before the prototype communities were completed. Today, eight of the original nine prototype communities continue to provide accessible

housing, suggesting the need to reconsider what constitutes failed policy. The St. Louis prototype community was razed along with the rest of LeClede Town. The prototype

dwellings located in competitive housing markets such as Jersey City, Seattle, Memphis, and Sacramento however, have increased in value over time. The early racial, income,

and occupational diversity that characterized the prototype communities have not always persisted over time.

The racially and economically mixed population of New Horizons Village chronicled by HUD in 1972 changed within a short time, and the more affluent residents—white and Black—began leaving. Financial problems soon plagued the cooperative that had purchased the units from the developer with the backing of the NHPC.

OB did not end with the construction of the nine prototype communities. Phase III continued after Romney left office in January 1973. Fourteen of the housing systems providers that participated in OB built 131 projects in 29 states with funds set aside from the public housing and other subsidy programs. When Phase III set-aside funds were exhausted, Forest City-Dillon (now Forest City-Ratner) successfully marketed its prototype dwelling—just as Romney had intended—to both privately and publicly funded developers.

ASSESSING THE PROGRAM

OB fell short in realizing the goal of transforming the low- and middle-income housing market with factory-built housing. Despite the involvement of aerospace firms such as Boeing, no dramatic space-age type of technological advance took place in home construction. OB’s accomplishments remain overlooked or ignored. HUD required contractors to consult with potential residents, undertake good-faith efforts to hire minorities at all job levels, and negotiate contracts with minority-owned firms. The department strengthened the existing infrastructure of oversight and accountability needed to ensure housing accessibility and Equal Opportunity Employment.

The OB prototype communities offered an alternative to the proliferation of unplanned subdivisions that extended or reinforced segregation by class, color, religion, and income. They helped define what mixed-income, desegregated residential places looked like, and reinforced the importance of site planning in the development of housing for people of all backgrounds and income ranges. OB planners produced site plans seeking, as stated in the program, to “demonstrate new land concepts and housing patterns that HUD hopes will provide some incentive for change.”

Kristin Szylvian (“Operations Breakthrough’s Forgotten Prototype Communities”) is graduate director of public history at St. John’s University. Dr. Szylvian’s research focuses on urban history and housing and urban planning policy. Her articles have appeared in Buildings and Landscapes, The Journal of Urban History, Planning Perspectives, and Environmental History.