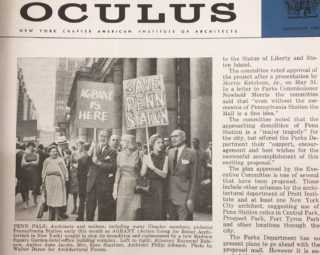

In October, Oculus achieved octogenarian status and the distinction of being one of the longest running architecture publications in the United States. The very first issue (front page pictured below), invited AIANY members to participate in a naming contest for the chapter newsletter. The publication was reimagined and kept visually relevant over the years, thanks to notable graphic designers like Arnold Saks and Pentagram. But while the design, frequency, and guiding editorial hand has changed over the decades, the subject matter has not: the ideas, activity, and professional concerns of AIANY Chapter members. To peruse the Oculus archive is to read a history of the built environment of New York and of those who forged it. For the magazine’s 80th birthday, we asked three former Oculus editors to reflect on their own distinctive tenures.

—Molly Heintz

IN THE ZONE

Suzanne Stephens, now deputy editor of Architectural Record, was the editor of Oculus from 1989 to 1994. She spoke to Andrea Monfried, now chair of the AIANY Oculus Committee and former Oculus staffer, about some standout memories.

Andrea Monfried: I remember a little bit of your early time at Oculus. You started in 1989, and I was there with you from 1990 to 1992. C. Ray Smith was the editor before you; is that correct?

Suzanne Stephens: Yes, but he had died. George Lewis was the executive director, so it was more of a gentlemanly kind of publication. Lenore Lucey, the new director, was the acting editor for a year while they were looking around. I was asked in for an interview, but they made it clear that I was supposed to show copy to them before it went to the printer. I said, “No way—I have to have editorial control.” They thought about it and said, “Okay, we’ll give you editorial control.” They really didn’t understand what that meant.

AM: Did you have an overall goal when you went to Oculus?

SS: I had been the editor of Skyline, the “tabloid” of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, and I believed that Oculus should stir up some trouble. It needed to raise people’s awareness of things that were going wrong in their communities and the city, with zoning, developers’ greed, and bad architecture. We also tried to be about architecture as a culture. A lot of it was a Skyline-esque kind of mélange of things we thought would interest the reader, but it was geared to the AIA reader. It was not geared to anybody else.

AM: Just as I was joining Oculus as your deputy editor, there was a little flip-out at the AIA. You had started a special zoning committee. That was maybe the first time Oculus had taken on an advocacy role.

SS: I think the AIA got upset because the committee was formed by Oculus, not the Chapter, and even though the team included important AIA Chapter members, the Chapter itself didn’t have any control over it. And the Chapter had its own committees that weren’t getting publicity from Oculus! I see now why they were upset. But the Oculus zoning committee at least was productive. We devoted six issues to the topic: June 1990, September 1990, February 1991, February 1993, February 1994, and April 1994.

It started because a young architect, James Gauer, came up with the idea and organized the Special Feature Committee on Zoning on the Upper East Side for Oculus. Gauer had gone to a meeting of Community Board 8 on new city zoning. Jim was concerned about high towers, no plazas, and no light. So the committee examined 59th to 96th Street and Third Avenue to York Avenue, the far East Side. The first report in Oculus (June 1990) was called “Zonophilia Runs Rampant on the Upper East Side.”

The committee included not only Gauer but Peter De Witt, then of Beyer Blinder Belle; Bruce Fowle, then of Fox & Fowle; James Garrison, then of James Stewart Polshek and Partners; Michael Kwartler, architect (and zoning specialist); Peter Samton, then of Gruzen, Samton, Steinglass; Marilyn Taylor, of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill; and architect Craig Whitaker. Many were major players in the city planning and architecture community at that time. We organized roundtables and came up with diagrams, drawings, and zoning proposals. We suggested setbacks, but the main thing was to not have wasted plazas and monotonous shoe-box-on-end towers.

The February 1991 issue of Oculus reprinted a memo we sent to the city planning head, Richard Schaffer. We outlined everything: the plaza bonus should be eliminated, the size of the avenue zoning district should be narrowed from 125 to 100 feet deep, etc. Did it ever get made into law? No. Did we at least get some attention? Yes. Did it show that the architects were trying to do something for the committee? Yes.

AM: There were a number of other ongoing stories.

SS: Under my editorship, Oculus ran articles called “The Age of Consent,” which was about the consent decree the AIA signed with the Justice Department in 1990 after being accused of price fixing. We got a lawyer to write two articles about the implications. It was very interesting. We were against Donald Trump’s Riverside South development, and we had a special article called “Dumping Trump, the Aftermath,” which could be a great title now.

AM: I wrote a lot of the articles on Riverside South. I remember that whenever we were running over on copy, it was always my article that turned out to be mysteriously shorter. I wonder how that happened.

SS: I’m a good editor of somebody else’s prose. We also did things like “Spotlight on Young Architects;” “Architect Abuse,” about architects grabbing credit; and “The Sharks and the Guppies,” about how big firms step on little firms. As part of “Architect Abuse,” we ran months on Raj Ahuja. He was trying to take over Philip Johnson’s firm, and John Burgee was resisting it. There was a big lawsuit. It’s in the new book by Mark Lamster.

AM: After the first issue under your editorship, you got some cranky letters from traditionalists in the AIA. Do you remember how you responded?

SS: Yes: De gustibus non est disputandum. “There’s no accounting for taste.” It was fun. It was a moment.

MENTOR-IN-CHIEF

Jayne Merkel edited Oculus from 1994 to 2002 after serving as architecture critic of The Cincinnati Enquirer. She looked back on her tenure with one of her contributors, Alexander Gorlin, FAIA, who compiled this piece.

When I edited Oculus, it was an independent publication, published by the AIA but not specifically about the AIA and its members. There was a section in the back about AIA business, committees, and active members’ activities. This editorial independence had been the tradition for a long time, and certainly it was the practice when I took over and Bart Voorsanger was president of the AIA New York Chapter. The idea was to provide members and other readers with information about architecture and New York architects without the influence of members who were active in the organization. The editors and writers were the judges of the content, as they are at most magazines.

Soon after I arrived, we were able to have our graphic designer, Michael Gericke of Pentagram, redesign our small black-and-white publication, adding red to the palette and giving Oculus a more polished architectural look.

Probably the most exciting and, in the long term, the most important thing we did was to create the Emerging Writers Program. When I took over at Oculus, I had been directing the graduate program in architecture and design criticism at Parsons School of Design/The New School for Social Research. One of our students once asked if it might be possible to publish some of the interesting work the students were doing. Another student, with rather significant economic resources, offered to donate $5,000 to make a publication possible. The writing program was then disbanded, however. On the advice of architect Susana Torre, who was directing the Parsons architecture program at the time, I asked the school to donate the money to Oculus, and with that money, we were able to pay emerging writers to contribute articles. (We called them “emerging” because not all were young—some were midcareer.) A number of the writers who contributed to Oculus went on to be significant writers, many of whom now have books to their credit. Among the participants in the Emerging Writers Program were Matthew Barhydt, Andrew Blum, Todd Bressi, Oliver Freundlich, Kira Gould, Gavin Keeney, Craig Kellogg, Laurie Kerr, Lester Korzilius, Amy Lamberti, Philip Nobel, Nina Rappaport, David Sokol, Tess Taylor, Kentaro Tsubaki, and Suzanne Wertz.

We also published commentary from architects, professional critics, and prominent academics. Among the architects were Andre Chaszar, Richard Dattner, Bruce Fowle, Deborah Gans, Mark Ginsberg, Alexander Gorlin, Michael Graves, Sharon Haar, Kyle Johnson, Diane Lewis, Arthur Rosenblatt, Rob Siegel, Susana Torre, and Claire Weisz.

Among the critics and scholars who contributed to our pages were Robert Benson, Aaron Betsky, Peter Blake, Stanley Collyer, Paul Goldberger, Kenneth Jackson, John Johanson, Stephen Kliment, Carol Krinsky, Noel Millea, Wendy Moonan, William Morgan, Janet Parks, Adolf Placzek, Victoria Reed, Irving Sandler, Robert Sargent, Mildred Schmertz, Helen Searing, and Rosemary Wakeman.

I was editor during 9/11, so the most intense issue was the one in which we interviewed architects about their experiences during and after the attacks. We were able to bring everyone together—before the committees were formed and planning for rebuilding began—to commiserate and share experiences and ideas.

We wrote not only about new buildings, we covered lectures, panel discussions, books, and exhibitions. When websites first appeared, Lester Korzilius, who was one of our most enthusiastic book reviewers, critiqued those as well. We also invited prominent academic architects and historians to contribute, so the dialogue was often challenging.

One thing that struck me most as I edited Oculus and got to know the entire New York architectural community was what a distorted view I’d had of New York architecture when I lived in Cincinnati, even though I came here often and wrote for national magazines. I soon saw there was so much more talent here than I’d realized. A number of the “famous” architects, who got a lot of press, actually did very little, while there were dozens of significant practitioners, in both small and large firms, doing really important, even pioneering work. We tried to call attention to them, but there is still a significant gap between fame and contribution.

NEXT GEN ADVOCATE

By Kristen Richards, Hon. AIA, Hon. ASLA.

Kristen Richards served as editor-in-chief of Oculus magazine from 2003 to 2016, and is co-founder and editor-in-chief of ArchNewsNow.com, launched in 2002.

I was delighted to be invited to a pen a piece for this issue of Oculus commemorating its 80th anniversary. I can only imagine what New York City was like when the publication launched in 1938. I don’t have to imagine what the city was like in late 2002, when—in AIANY’s (rather dreary) offices hidden away on an upper floor of the New York Design Center at 200 Lexington—I signed on to be the editor. After a year on hiatus, the black-and-white monthly was to reemerge for its 65th year in a new incarnation as a full-color quarterly journal with the Spring 2003 issue.

Ground Zero wasn’t smoldering anymore, but the city was still hurting. Gloomy forecasts declared that no one would build tall in the city again, which did not bode well for the architecture and design community. But AIANY would have none of it. Within days following 9/11, Chapter members spearheaded the formation of New York New Visions, the pro bono coalition of industry organizations that helped guide the conversation about the rebuilding of Lower Manhattan.

The Chapter also proceeded with plans for a street-level Center for Architecture that would, for the first time, give its members and others a platform for public discussion and debate, and space for exhibitions and educational programs (and fun!). By the end of 2003, the Center was in full swing, and became rich fodder for Oculus, resulting in some wonderful collaborations with Chapter presidents and exhibition curators.

As I began pondering this column, it struck me: How can I parse, in just a few words, 13 years of in-the-moment-until-the-next-moment that goes into producing a (hopefully) engaging, informative, and provocative journal? Highlight my favorite issues of the magazine? An impossible task.

But among the highlights are the concerns that the Chapter, Center, and this magazine tackled and supported—including advocacy and social impact. It wasn’t that long ago that “do-gooder” designers, though lauded, were often considered to be on the fringes of the profession. It is now an accepted, respected, and—increasingly—expected part of many firms and companies across the industry.

And most dear to my heart was the opportunity to advocate for the next generation of talent, beginning with the Spring 2004 issue, “New York Next: Faces of the Future,” many of whom are now solidly established. It was always a treat to dedicate pages to the AIANY Emerging New York Architects (ENYA) and New Practices Committees and the Center for Architecture Foundation’s K-12 programs.

An interesting where-are-they-now exercise: In the very first issue (“Past as Prelude”), I wrote that the fates of the High Line, Saarinen’s TWA Terminal, the Meatpacking District (known as Gansevoort Market before “rebranding”), Edward Durell Stone’s 2 Columbus Circle, and Hudson Yards, among others, were in limbo. Their stories have had (mostly) happy endings and, along with the transformation of post-industrial waterfront wastelands into miles and miles of joyful public spaces, were spotlighted in the pages of Oculus.

What made my tenure with Oculus—and the Chapter and the Center—so rewarding was the synergy and camaraderie, which, in turn, led to an even greater sense of us all being connected to the city, and continues today. We went through a lot together—the 2008 financial crisis that hit our city and our industry hard, then slowly coming back only to be hammered by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, to name but two—and we came through with flying colors.

I am so happy to see the magazine continue under thoughtful editorial leadership and an always-supportive Oculus Committee. And I’m so proud to be part of its legacy. Here’s to the next 80 years!