Ask Danish architect Steen Gissel of ERIK Arkitekter about how to design more effective, efficient, and humane prisons, and his advice is to avoid studying prisons at all costs. Gissel gets asked about correctional facilities a lot because of his work on Halden Prison, a maximum-security facility that opened in Norway in 2010 and has been celebrated for its beautiful, even bucolic, design. (Living spaces resemble catalogue-ready Scandinavian college dorms, and inmates can pick blueberries on the wooded grounds.) But his most important message for architects designing these institutions is to remember that architecture simply isn’t that important. “It pains me to say as an architect, but architecture is much less important than culture and political discourse,” he says. “I like to talk more about the concept of punishment and incarceration, rather than architectural drawings.”

The challenges of designing prisons, jails, courthouses, and correctional facilities—distilling local and national visions of crime, punishment, and forgiveness into physical reality—has always been a complicated one. Architects need to balance unique safety and security concerns and, in some cases, ask whether such structures should even be built. Alone among peer nations in terms of prisoner population, the United States, and the continued expansion of its carceral system, embodies a dark form of exceptional-ism that challenges architects working in this field. One of the defining images of last summer’s protests over George Floyd’s murder was the burning down of a police station in Minneapolis. Amid calls of “defund the police” and larger initiatives to rethink community safety and sentencing, the nation seems both tethered to physical monuments of its police and prison systems, and ready to get rid of them.

Increasingly, however, prison and jail design is rapidly evolving around the world, and best practices have found their way back to the U.S. Gissel says that the design challenges of creating a more humane, livable prison pale next to the cultural shifts required to do so. But as the national conversation about policing and punishment continues, this may be a moment when such a shift in opinion, and therefore design, is possible. “It really comes down to the fact that incarceration is an alien concept to most people,” says Gissel. “People see pictures of Halden and say, ‘I’d like to live there.’ What they don’t understand when they see those glossy photos is that 99% of prisoners will tell you that the lack of freedom and being deprived of access to loved ones are the harshest punishments of all. Halden’s philosophy is simply that the state of incarceration is enough. There will be no further punishment than that.”

The U.S. is certainly an outlier, spending $81 billion on public correctional facilities and housing 698 of every 100,000 Americans in prisons or jails, more than five times higher than the United Kingdom. Still, according to World Economic Forum statistics, prison populations are skyrocketing globally. The number of prisoners worldwide has grown 20% in the last 20 years. Concurrent to this boom in punishment, a number of prison systems and architects have created models for a better system, typically utilizing lessons from educational facilities and campuses to create places that offer prisoners a more supportive path back to society, compared to the sadly well-worn path towards recidivism and a return to jails.

Gissel says that a central design philosophy at Halden is personal responsibility. Prisoners can shop at an on-site store for food and personal goods, cook their own meals in kitchens (well stocked with knives), and spend considerable time at work or in class. The layout of the grounds, a campus of separate buildings fashioned after a Norwegian town square, creates an environment as close to an approximation of normal life as possible behind walls and fences. Administrators have found that threatening the loss of these activities and freedoms is a much stronger deterrent than those found in U.S. prison designs, which are typically spaces of punishment, deprivation, and isolation that restrict rather than rehabilitate, and breed retaliatory behavior. “If I take everything from you, your actions no longer have consequences since I can’t punish you any further,” says Gissel. “As a result of that approach, there are no longer consequences to one’s actions.”

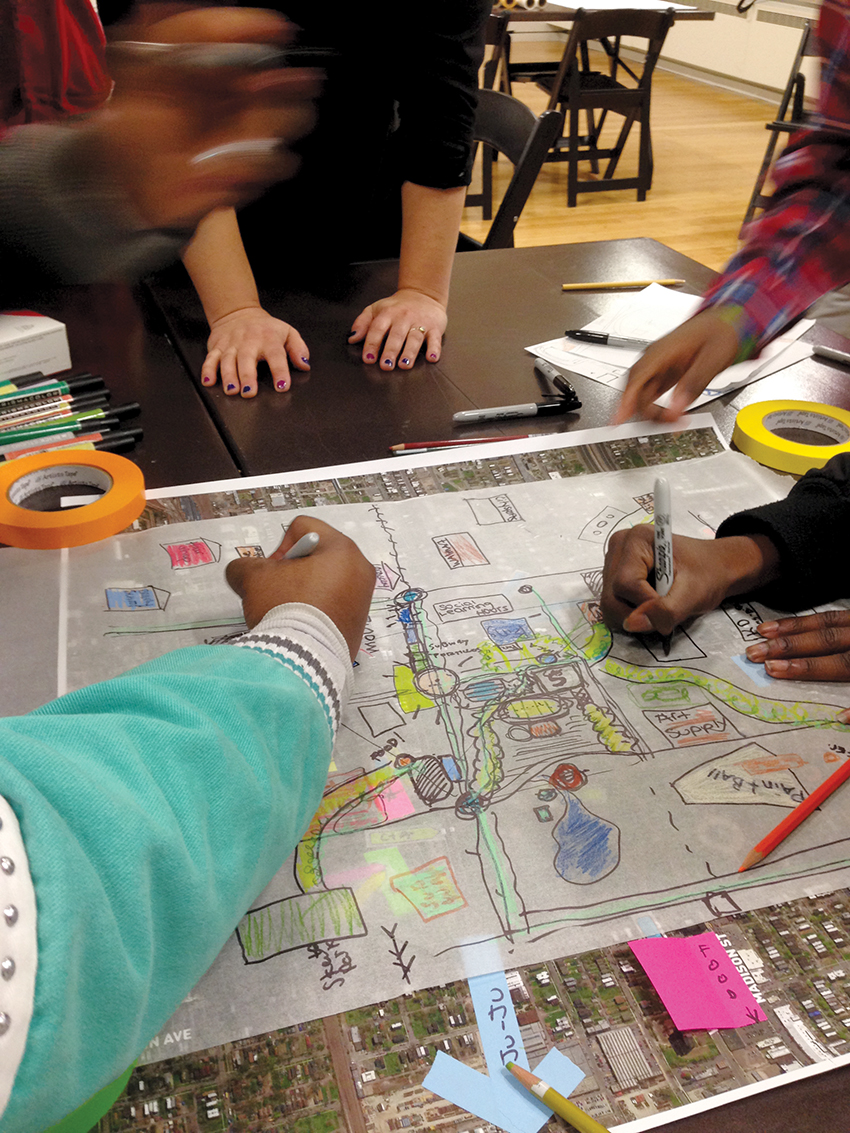

Deprivation doesn’t stop violence, nor does it help prepare inmates for life after prison; it also inflicts damage upon the guards, the inmates’ families, and the wider community. Bureau of Justice statistics indicate that 75% of women and 63% of men behind bars already suffer from abuse, trauma, or mental illness. Chicago architect Jeanne Gang, FAIA, believes that community investment should be the guiding vision for any reckoning and redesign concerning justice, police, and prisons. Her firm presented an in-depth, self-initiated research project called “Polis Station” at the Chicago Architecture Biennial in 2015, which traced the history of American police forces and offered strategies for redesigning police stations by turning existing buildings into multiuse community hubs. “In essence, Polis was about community building, not just building for police,” says Gang. “The idea of putting other services in these buildings—such as mental health services and community amenities—is still a good model of what community-oriented building could be like.

But deeper problems need to be fixed, and reform needs to happen at every level.” Part of Gang’s vision was simply reconsidering who these buildings are meant to serve. Police stations can be made smaller, more approachable, and less fortress-like, which creates rapport and trust between citizens and police. Adding basketball courts, WiFi, mental health clinics, and community meeting spaces can help build reliance and legitimacy, and ideally stop someone from entering the justice system entirely.

Prisons can also be reimagined as places that benefit prisoners and their families, not simply warehouses for punishment built with bottom-line considerations in mind. In Norway, prisons are built smaller and positioned across the country, on the belief that housing inmates closer to families means more social connection and less recidivism. Those approaches help explain while only 20% of Norway’s ex-convicts return to prison within two years of release, compared to 60% in the U.S.

Designing for rehabilitation “just flows from the philosophy,” says Gissel. “It seems natural to design a prison like this.” One tactic Gissel and his team used to guarantee a less restrictive design was to ban the use of terms like “cellblock” and “warden” during the design phase. If the term “housing unit” is employed, it’s less likely the end result will be a sparse, cramped shed of concrete block. Storstrom Prison in Denmark, designed by C.F. Møller Architects and opened in 2017, is built around a provincial town model. Featuring white-brick dorms with specially designed cells, it is made with curved walls and furniture that maximize natural light and space, allow guards to more easily observe inmates, and reduce the risk of injury or self-harm from furniture. Facilities such as Leoben in Austria, with sleek glass façades and refined private rooms with kitchenettes, and Bastoy in Norway, a prison facility on an island that features wooden eco-cottages and activities like horseback riding, challenge the concept that architecture has to be part of the punishment.

Philosophical shifts can alter design and ultimately lead to a reevaluation of how a prison fits into a city. In Nanterre, a suburb of Paris, local architecture firm LAN designed a minimum-security prison on a main road in a more industrial section of town. It features a towering wall of gridded CorTen steel that creates a sense of transparency and connection to the urban fabric. Architect Umberto Napolitano looked at the wall, which stands in front of a pastel-colored basketball court and prisoner dorms, as a kind of interface with the city, “challenging the idea of the prison-city relationship,” he says. The prison program allows inmates to circulate in town for work, with their time away from prison increasing gradually as they get closer to release. The façade indicates that the prison is a part of the city, not a void outside of society. “We wanted it to look a little more like a museum or office building, something abstract, and looked for a material that could be perforated, change with the weather, and change with time,” says Napolitano on the metaphorical nature of the prison’s exterior wall. “It’s a secure steel wall, but it’s also perforated. It’s sweet and soft, and seen in a different light. It changes the way you see the same material.”

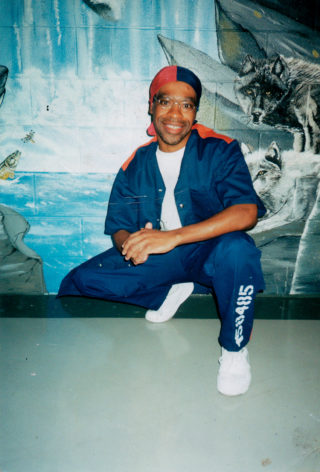

There are signs that the U.S. has begun adopting less punitive approaches to new prison designs as well. In San Diego, the Las Colinas Detention and Reentry Facility, a joint project between HMC and KMD that opened in 2015 and helps female prisoners readapt before release, was built around a campus model: Interiors are fashioned around natural light, murals feature inspiring nature scenes, and landscaping includes walking paths, amphitheaters, and space for yoga. “It isn’t all bars like you see in a movie,” says Robin Schwab, a former inmate. “This environment is conducive to rehabilitation.” In Atlanta, Deanna Van Buren, who co-founded the non-profit design firm Designing Justice + Designing Spaces, has spearheaded the creation of a new Atlanta justice center that would replace a 1,300-inmate prison with community-focused features, such as a reentry program, classrooms, and parks and urban green space. Months of community meetings guaranteed that the design elements reflected community needs and aspirations.

The center is an example of a divest-invest model, a vision echoed by many Black Lives Matter and local justice groups, that prioritizes a new kind of infrastructure based on uplift and assistance. Van Buren points to support from Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who proposed a $400 million bond to help fund the adaptive reuse of the city’s jail facility, as a sign that political will is growing for these kinds of changes. Other indications of a cultural shift in the public’s view of policing and punishment that may trickle down to architecture and design include the “defund the police” movement in Minneapolis and the city council’s move to rethink public safety, and the recent passage of Measure J in Los Angeles, which would divert hundreds of millions of dollars away from police and towards investments in incarceration alternatives and social services. The grassroots push for reform could help bridge the gap between the reality of the American criminal justice system and aspirational designs elsewhere.

“Maybe our strength is that we do better engagement with different community groups and stakeholders, and really identify what’s missing in our neighborhoods,” says Gang. “In the past, architects were so afraid of design by committee. But we need to realize we’re still the ultimate architect and designer. We’re just getting a lot better at listening and understanding what needs to be designed.”

Patrick Sisson (“Reconceiving Justice” and “Roads, Not Walls”) is a journalist and Chicago expat living in Los Angeles. He is interested in cities, transportation, architecture, and consumer trends—and the way these forces shape culture and urban life. His writing, which also explores music, art, and technology, has been published by the Verge, Vox, Pitchfork, Curbed, and Wax Poetics. He is the author of This is Chicago, a book about the history of design and designers in Chicago, published in 2015.