Architecture is the heart of the designed environment. Its arteries enliven our existence, interplaying with other types of design and a variety of design elements: communication, wayfinding, urbanism, landscape, audiovisual, color, wardrobe. They operate in complement to one another, constructing our tangible and spatial-emotional experiences—including that of incarceration, a manifestation of the prison-industrial behemoth as we know it in America today. Multiple industries throughout the nation bear degrees of responsibility for incarceration’s rampant maladies; not all, however, acknowledge their accountability. Last September, AIA New York Chapter took a stand when it released a call-to-action statement dissuading architects from designing “spaces of incarceration,” urging them instead to focus on “supporting the creation of new systems, processes, and typologies” for reform. The Criminal Justice Facilities Statement pledged programming and exhibitions that would “examine architecture’s role in the criminal justice system…while highlighting the voices of those who have suffered” within and because of it.

The design of wardrobe in the carceral setting is where my interest intersects with that of architecture: both evidence the construction of incarceration and are entangled with its capitalist industries. Both are embodied elements of its lived experience; both are signifying and significant.

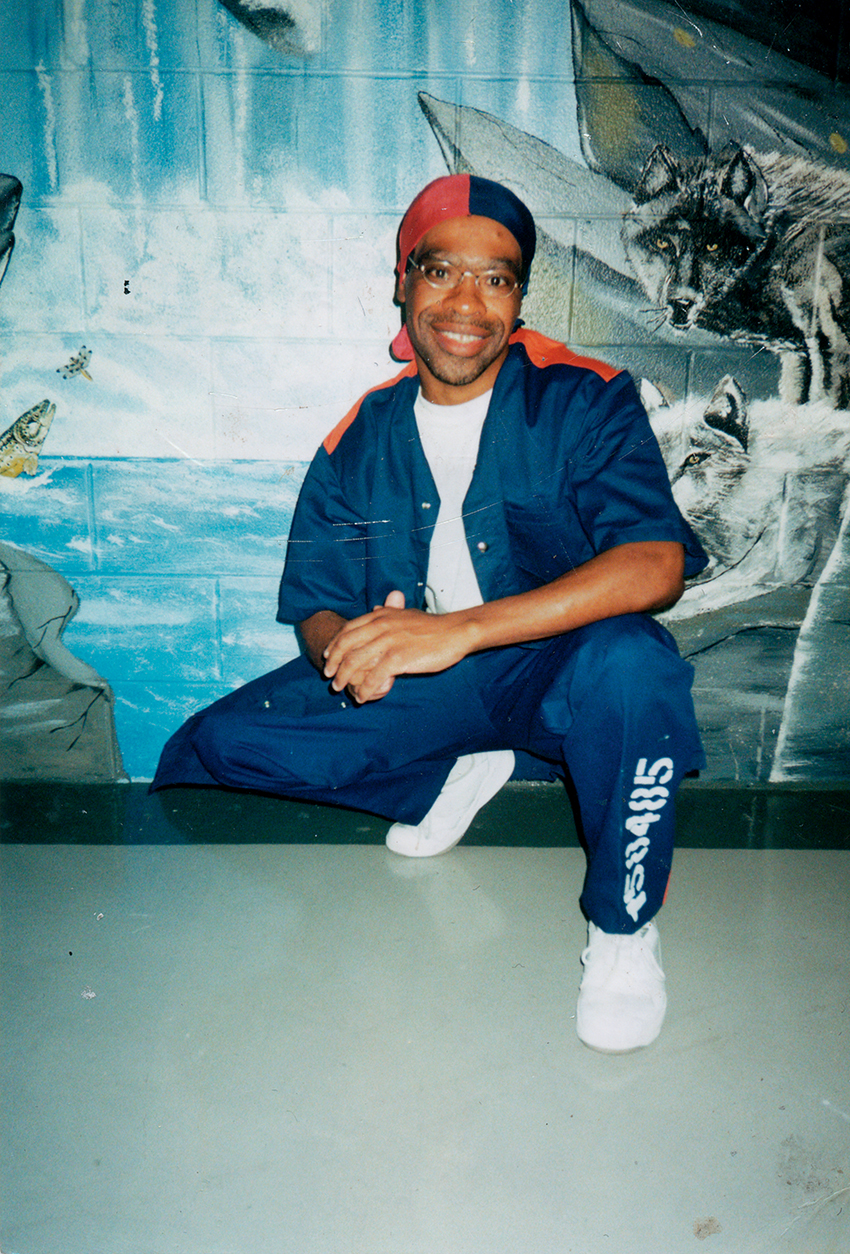

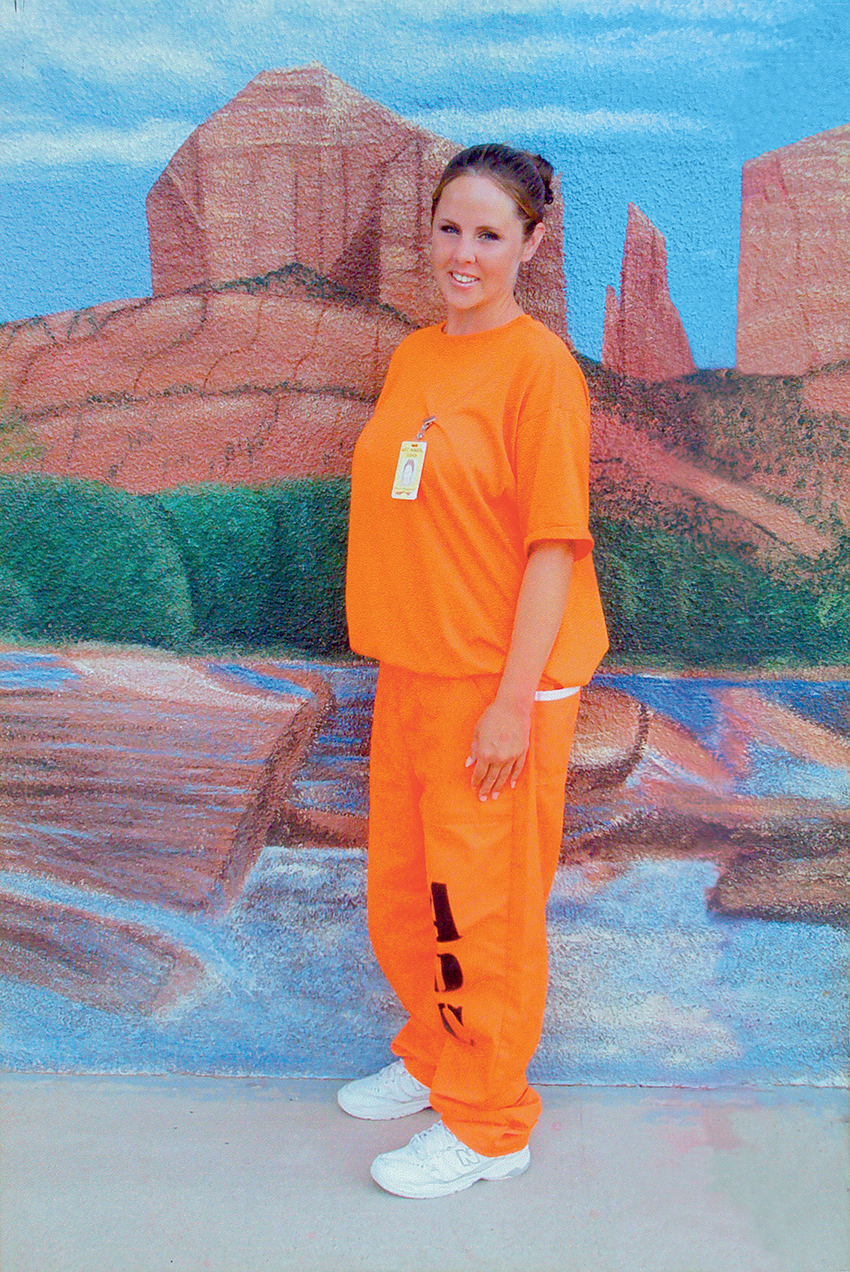

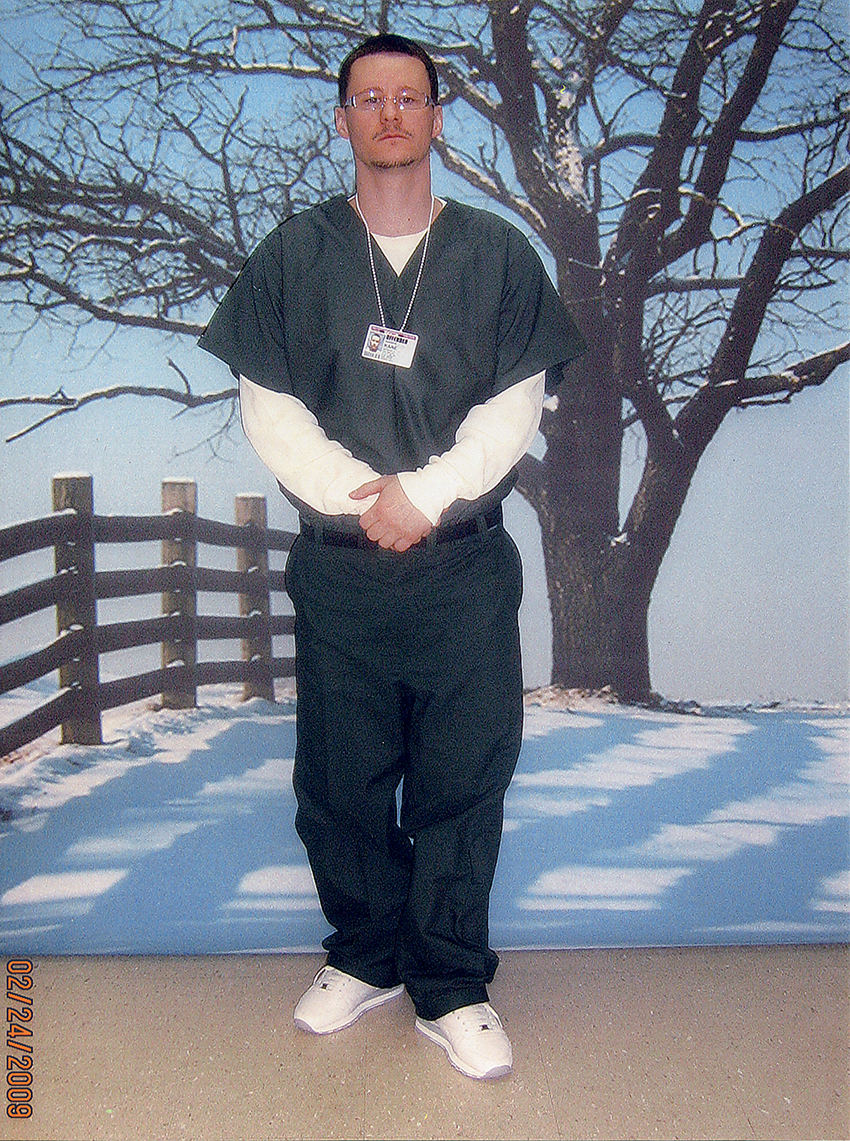

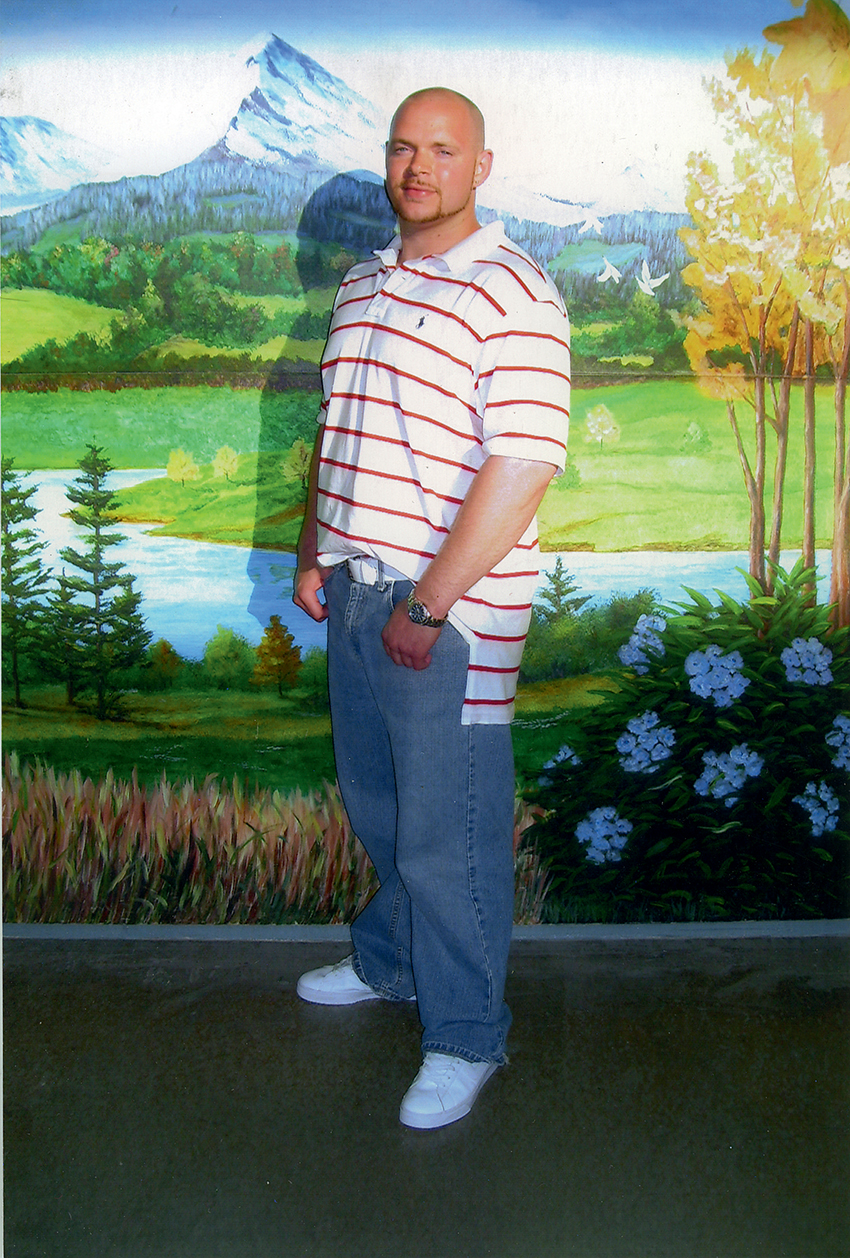

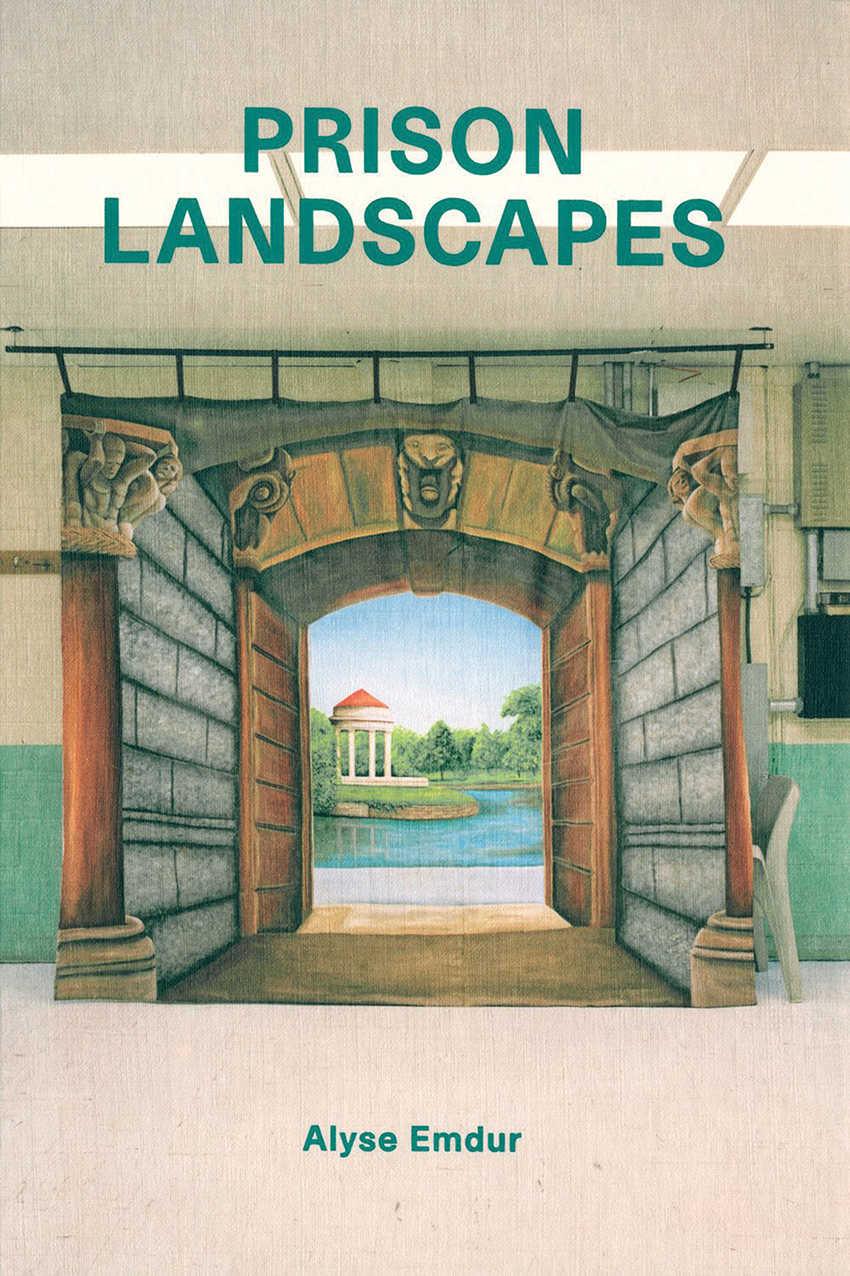

The following insights represent a collaborative effort, a response to AIANY’s pledge to highlight the voices of those who have suffered under incarceration’s grave influence. Artist Alyse Emdur, inspired by memories of growing up visiting her older brother when he was incarcerated, dedicated a full body of work to scenes of self-presentation in prisons. The photographs shown here are from this project, published as Prison Landscapes (2012). The book contains both Emdur’s epistolary correspondences with incarcerated individuals and their submissions to her, for publication, of select self-styled pictures from visitation rooms in which makeshift backdrops (the “landscapes”) were often set up for photo opportunities. Davon Woodley, a New York-based entrepreneur and social justice advocate, also offers his lived experience to this piece. Formerly incarcerated, Woodley now roots his professional activism in his story.

“My thing was sweaters,” he says. “Hot or cold, send me a nice polo or sweater. I still wanted to be fly—I still wanted to look human.” Sweaters from the outside were a small victory for humanity, reclaiming selfhood from the would-be eclipsing signifier of his New York State-assigned corrections uniform.

Dr. Richard Wener is a professor of environmental psychology at NYU Tandon School of Engineering, whose career focus is correctional architecture. “Part of being in prison is is systematically taking things away from people,” says Wener. “Take away your right to privacy, to control, to access to yourself, to your body—all sorts of things. The clothing connects with all that.” Woodley concurs that “the uniform plays into the structural form of the prison industrial complex. But I always thought it was ironic that institutions of any kind have uniforms—even colleges. They are institutions; they have alma mater colors.” Yet for people who are incarcerated, he says, “it feels like this is the only color set that is supposed to represent the fact that you lost your freedom—regardless of if you’ve been convicted or not.”

Indeed, the unique design choices driving the sartorial prescriptions in prisons and jails signify guiltiness, whether or not legal guilt is factual. They signify a transference of ownership from the self and the body to the prosecuting superstructure (county, state, federal). Nomenclature shifts—most often visibly, a transcription displayed externally—from a name to a number.

Design has the power to make choices, just as it has the power to take choice or name away. To design for anti-recidivism, Wener says, “You want incarcerated citizens to exist in the place where they’re the least separated, where there’s the smallest possible schism between their community and where they are.” He describes the factors that could be manipulated to reduce that schism: buildings, work, food, colors, clothes. The point being, the material environment of prisons and jails has agency, so the designers of the material environment of prison and jails have agency.

With regard to colors and clothes, Woodley says that “seeing anybody in green pants is triggering.” But what he retained from his experience of incarceration is not entirely traumatic. “The thing people would do the most that I thought was really cool,” he says, is that during visitation they “would get a friend on the outside who wore the same shoe size, or close to the same size, and when they’d see each other, they would switch shoes under the table.” It was a stick-it-to-the-system ingenuity, a defiance of the oppressive superstructural complex to the tune of self-retention. “Somebody could have the newly released Jordans in prison,” he says. “You wanted to go that far to risk getting a ticket—to just have some form of normality.” It was speech through clothing, a way to voice power and pride while threatened by a system designed to strip you bare.

The threat of the system lingers outside its carceral cages. We with existing agency, designers, are charged with lessening the threat. We are charged with bringing the lifeblood back to the beating heart of architecture—this time, by refusing to participate in it. This time, by envisioning our role in a future that designs protections for, instead of tools to neuter, selfhood.

Emily R. Pellerin (“Reconceiving Justice” and “Self v. System”) is a Brooklyn-based writer and communications strategist with a focus on art, design, and creative communities. Rooted in design research and journalistic principles, her strategy work concentrates on brand storytelling, content development, editorial direction, and cultural programming. Emily’s recent graduate thesis is a critical discourse on the prison uniform as an article of mate-rial culture, the design of both built and systemic carceral environments, and racial and criminal justice.