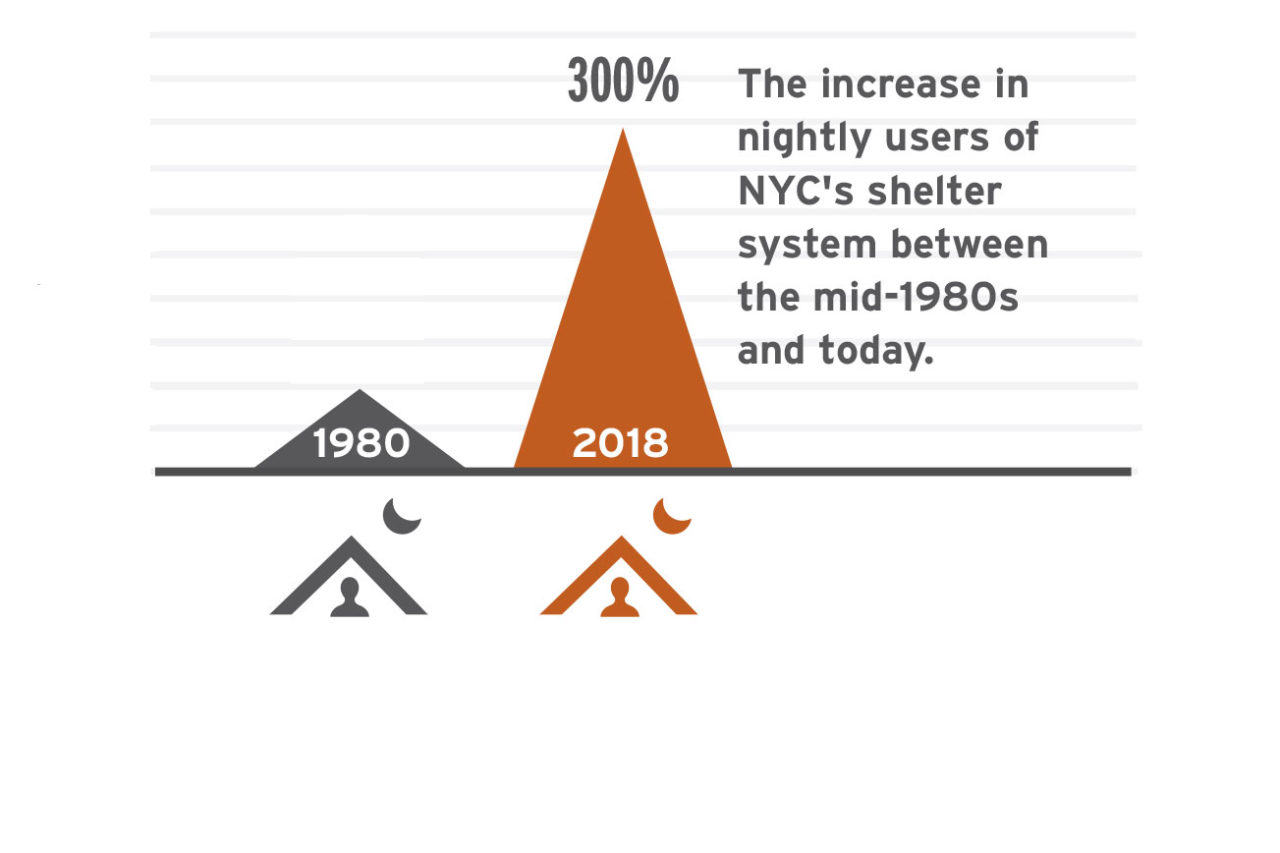

A landmark class-action lawsuit on behalf of homeless men in New York City established the right to shelter in the city in 1981, and soon expanded to women and families. At the time, the homeless crisis was highly visible everywhere—on the streets, under bridges, in homeless encampments, and in public parks. Since that lawsuit, the city has been court ordered to find a bed for every qualified person arriving at a shelter facility. The lawsuit also spurred the creation of an extensive infrastructure of nearly 500 facilities for overnight and longer-term shelter throughout the five boroughs. The Department of Homeless Services (DHS) now oversees a shelter system used by approximately 61,000 homeless NYC residents every night.

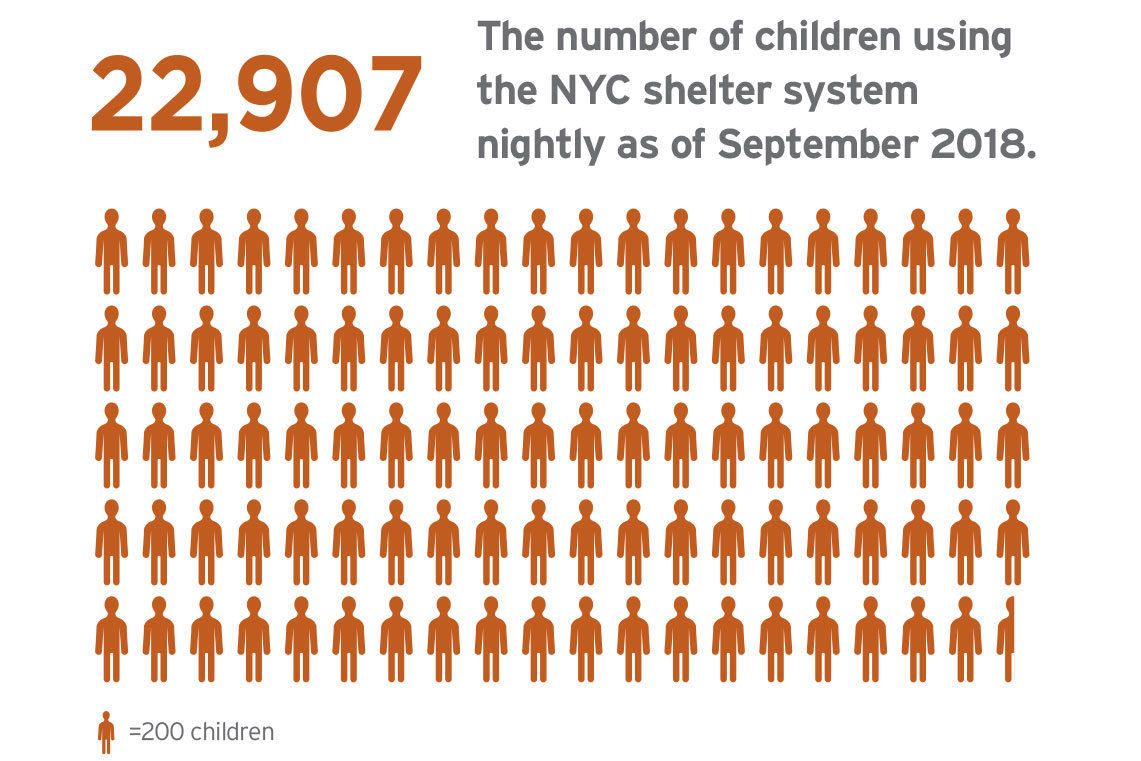

Haphazardly built over the last 40 years, the system is largely made of buildings not originally designed for the program needs of temporary shelter, known as “purpose-built” shelter. Particularly underserved by the facilities is a little-acknowledged population of 15,000 families and 22,500 kids. “About three-quarters of people who are homeless in shelters are families,” said Giselle Routhier, program director of Coalition for the Homeless, which led the right-to-shelter lawsuit. “Parents with kids often don’t fit the stereotype when people think of homelessness; people are not aware of the depth of the crisis among families.”

Several innovative shelter and intake center projects by Edelman Sultan Knox Wood (ESKW), Curtis + Ginsberg, Marvel Architects, and Ennead aim to radically improve the jerry-built system. The most recent and possibly most groundbreaking project is the Reaching New Heights Residence at Landing Road, designed by ESKW for the Bowery Residents’ Committee (BRC). In 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio released Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City, a plan to replace ineffective shelters with high-quality ones. Landing Road, which opened earlier this year in Fordham Manor in the Bronx, is the first purpose-built shelter to open under the plan. Situated on a narrow, sloping site next to the Major Deegan Expressway, the structure is split into two functions: a 200-bed shelter on the lower two floors, and 135 units of low-income housing on the seven floors above. Syncopated with bright yellow Swisspearl fiber cement panels that project from bay windows, which extrude from a block-and-plank structure, the volume rolls downhill to become the Reaching New Heights homeless shelter. The shelter is marked off visually with lighter colored bricks and a setback above. Photovoltaics are installed on the rooftop to reduce energy consumption.

“We wanted the shelter to read as a clearly welcoming place, but also a safe place,” said Kimberly Murphy, project architect at ESKW. “Neither of these is meant to look institutional—they’re meant to look inviting to the community and offer a strong support for the clients who live inside.”

FOCUS ON THE FAMILY

By combining the shelter with long-term housing, Landing Road cleverly shifts the profits generated by its shelters to the low-income housing component. It sounds counterintuitive at first: Because the city and state are obligated to provide and fund the shelter and because the shelters normally lease their buildings from landlords who charge inflationary market-rate rents, owning the purpose-built shelter allows BRC to use the revenues the city pays it for the shelter facility to subsidize the rents of permanent apartments for very low-income and formerly homeless tenants. By owning the facility, the BRC can improve its quality of service to residents and provide 135 apartments to low-income tenants exiting the shelter system. “The hope is that it’s a model that can be replicated by other non-profit housing and shelter developers and providers,” said Murphy.

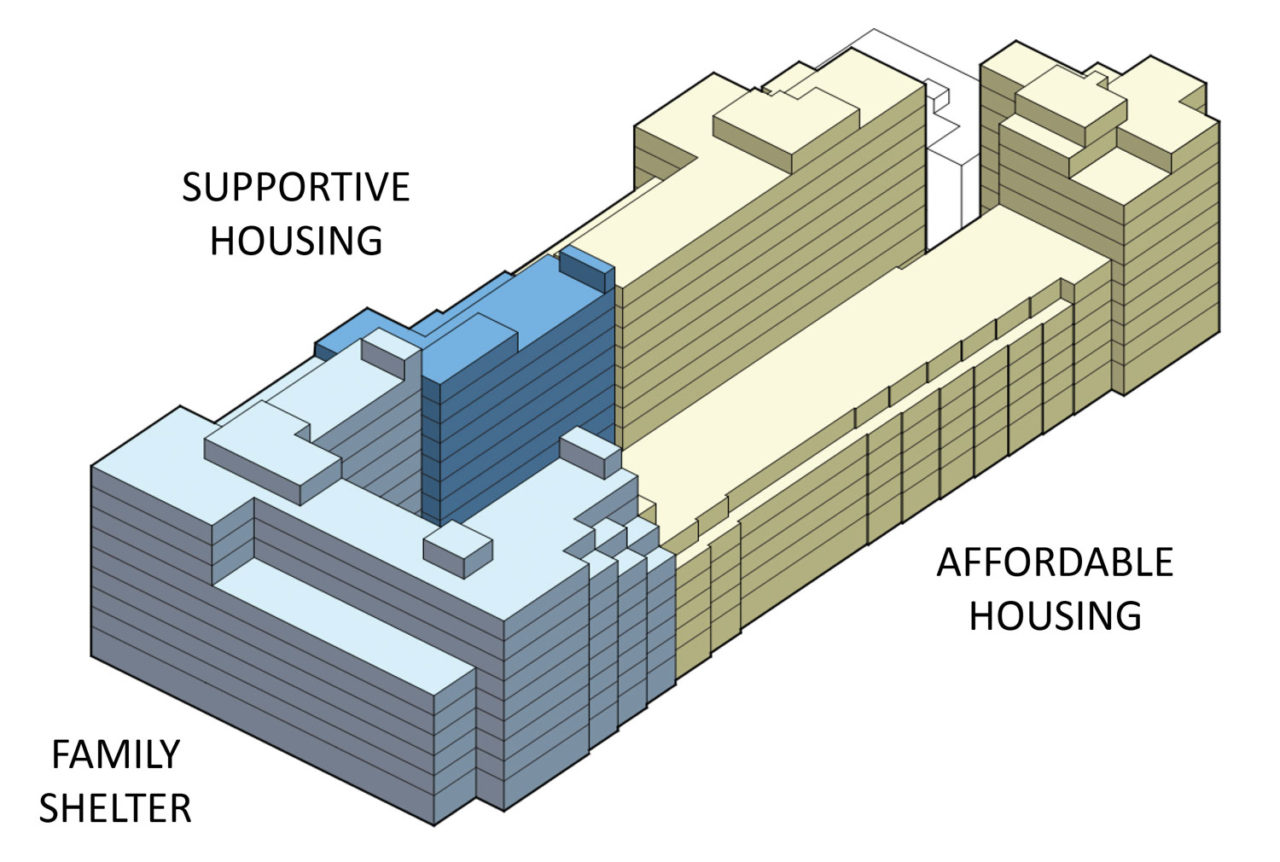

Quality of service and an integrated relationship with the neighborhood are also major features of the new 200-unit family shelters by Curtis + Ginsberg in East New York for HELP USA, just finishing schematic design. Planned to take up an entire square block near the Sutter Avenue L train, HELP ONE is set to replace a 200-unit family shelter built in 1987 with an upgraded facility. It also includes an affordable housing component, stacking the family shelter on one end of the block, and affordable apartments at the other.

With an entire block to play with, HELP and Mark Ginsberg, FAIA, worked together to rethink the program in a systematic way. “It’s unusual. You have the time and the luxury of back and forth to figure things out programmatically in a new way,” said Ginsberg. “We’re talking about doing passive housing and other things, but what’s really special is developing a design based on our client’s long-term experience with the programmatic issues.”

The theory behind the 1987 shelter held that exterior corridors and a single entry into the complex improved safety through open sightlines and an increased feeling of control. Services focused on the head of household to transition the family into employment and independent housing. “That worked for 10 years,” said HELP USA Chief of Staff Stephen Mott. “Now we have all this land and this opportunity to do something different.”

The main difference today comes with the acknowledgement that family shelters need to concentrate on the well-being of kids: On any given night, 15,000 families and 22,500 children reside in shelters, with half of those youngsters under six years of age. The average length of stay is 432 days, which means many children spend nearly a year and a half of their formative development stage in the system.

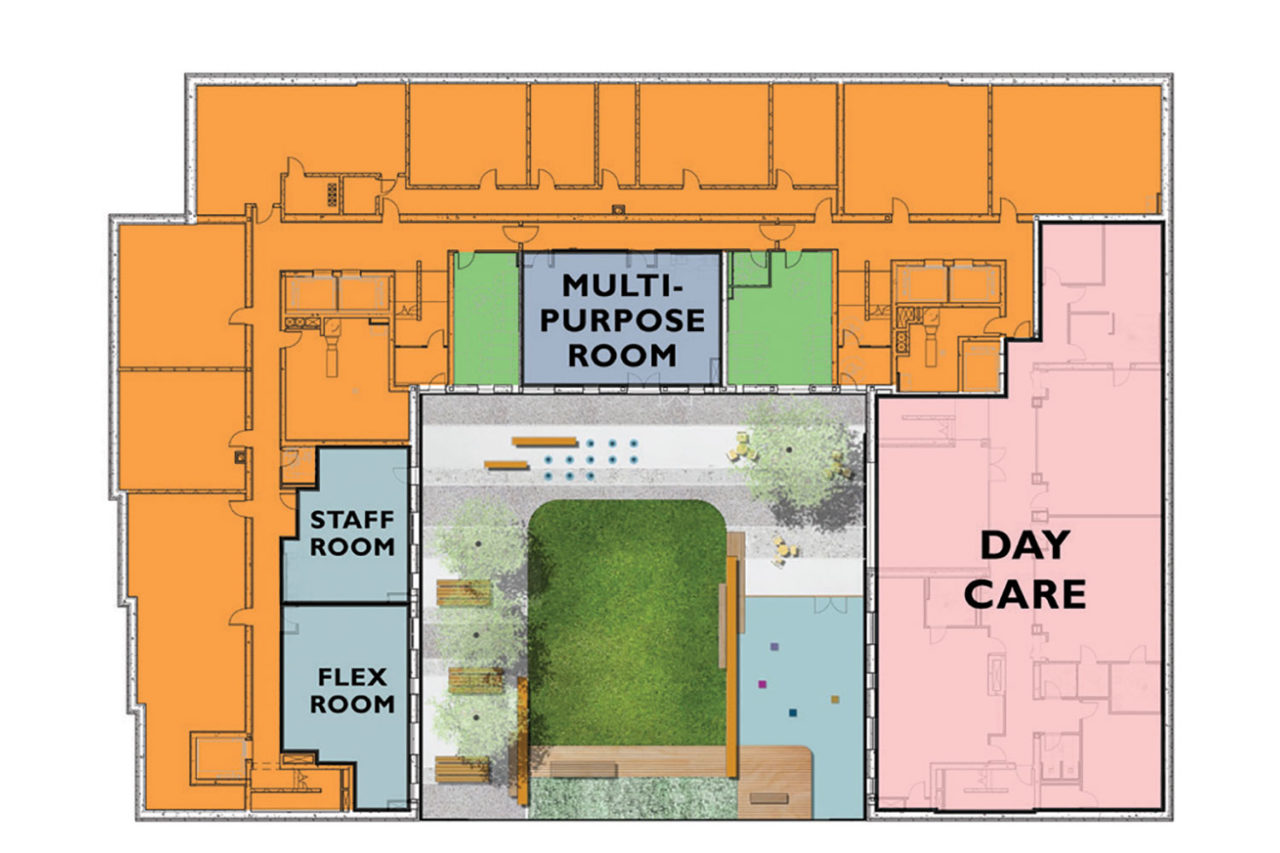

The more thoughtful design of the new HELP ONE facility provides the same number of units organized in smaller groups to promote sociability and easier access to services. Smaller-scale residential pods break down the institutional feeling of a large shelter, with support spaces and parenting rooms located in the middle of floors. On the lower levels, dedicated program areas like a daycare center, classrooms, and an outdoor garden create a sense of place and attempt to prevent traumatizing preschool-age kids. By scalloping the ground floor and interior courtyard to allow light onto the service level, Curtis + Ginsberg created an extra half-floor of flexible space for outdoor relaxation, staff breaks, laundry, and daycare. “Scooping out the courtyard gave us a lot more space to do some more programmatic things,” said Mott.

One reason communities react against the placement of shelters in neighborhoods may have little to do with prejudice or lack of good will. Poorly designed entry progressions cause lines to form outside, as residents wait to get inside before curfew. Unprotected outdoor spaces expose the residents to public view, a potential danger to them while socializing, lounging, and smoking. And when medical needs or conflicts occur as part of the stressful experience of homelessness, the arrival of emergency vehicles may cause a local disturbance. Recently, DHS has worked with shelters and first responders on plans to minimize commotion for neighbors.

Architecture is improving the quality of life in these facilities by incorporating spaces that ease conflict and help create sociable environments within the shelter and in relation to the surrounding neighborhood. In HELP ONE, this takes the form of a ground-floor commercial rental space and a double-height entrance hall that has the air of a boutique hotel lobby or a Gilded Age train station. These designs integrate the shelter in the neighborhood and dignify the perception of homelessness within the community.

The intake process is a unique part of the shelter system that purpose-built design stood to improve immensely, as evidenced by Ennead’s Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) Family Intake Center. Completed in 2011 in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx, it was designed by partner Todd Schliemann to replace a previous facility that wasn’t built for the purpose. The needs of the residents, said Schliemann, “are often greater than just a roof over their heads. There’s health issues, education of children, psychological issues, legal issues. The idea of the intake center is to try to figure out their needs and address them before you send them off in a bus.”

The logic of these programmatic flows was pivotal in the design of the building, which is sited on a sloping terrain. At the top of the hill, a stroller-friendly entrance and lobby provide extra room for security and check-in, after which families are escorted to elevators for interviews on the upper floors. Dedicated offices for interviews, medical exams, and meetings with psychologists and social workers enable administrators to determine the needs of clients. Families are then shepherded to a lower-level exit lounge featuring food, social spaces, and play areas, to wait for a bus to their overnight shelter. The process offers a humane environment that reduces the stress of an inherently traumatic experience. “The functional nature of the building is fairly straightforward,” said Schliemann, “but perhaps the most overriding thing we do is provide dignity for people who come asking for help.”

RETHINK AND REBUILD

An emerging set of best practices is also being applied in existing shelter facilities. At the 30th Street Intake Center, Marvel Architects is doing a complete retrofit of the city’s biggest and most important intake facility, the Bellevue 850-bed men’s overnight shelter. Still at an early stage of planning, the design would reconfigure sleeping arrangements, with beds grouped in threes to give clients additional space and privacy, reducing potential for tension. The entrance would carve out a large lounge area to decrease wait time on the street and improve quality of life for clients and community members. Dedicated program spaces would provide places for art workshops, job training, haircuts, and meetings with counselors, all geared toward improving self-esteem—important in moving toward a stable work environment and residential independence. Staging the renovation involves a complicated juggling act of creating an alternative shelter nearby during the two- to three-year retrofit.

“These can be sensitive neighborhood issues, so rather than building new shelters, the key solution is to rebuild,” said Jonathan Marvel. “Renovate the shelters that are already there and make them more efficient—adding a few beds, a few rooms—meeting the demand by not having to build new shelters. We came up with a device to work with city-owned properties within a five-minute walk of an existing building, to try to contain the population in the area they’re already in.”

LESSONS LEARNED

In the coming months, DHS expects to publish its Conscious Shelter Design Guidelines, a compilation of best practices for most effectively and thoughtfully utilizing shelter space. Developed in collaboration with AIA New York and Urban Design Forum (UDF), the publication will share examples of quick and inexpensive improvements that can be adopted throughout the shelter system. The guidelines take advantage of ingenuity in financing; feedback from the contractors and service providers who run the facilities; interviews with counselors, social workers, and maintenance and security staff; and the expertise of architects with decades of experience in the area. “The idea was to create guidelines using knowledge from young and veteran designers, practitioners from diverse backgrounds and professions, to analyze shelters and see what the easy wins were that could dignify the spaces for both staff and residents,” said UDF Director George Piazza.

As opposed to the highly visible homelessness of the 1980s, today’s crisis is being actively managed by city and shelter operators, providing housing to a population that has grown substantially while hardly being noticed. “It’s sort of hiding in plain sight,” said David Piscuskis of 1100 Architects, AIANY past president, who helped initiate the Conscious Shelter project. The invisibility of such a large number of homeless people is in some respects a sign of success. “It is important that the city has an emergency resource available,” said Routhier. “It stands in contrast to many other cities—L.A., Seattle, and others—that have had a vast increase in the number of people on the streets because there is no system in place to offer people.”

The goal of the shelter system today is to stabilize those going through hard times and help them get back to independent living. The more facilities incorporate design to improve how they relate to both clients and the surrounding community, the more the shelter system can be appreciated as a unique service that improves the well-being of the entire city. “All too often, people in shelters are an afterthought as far as the architecture community is concerned,” said Ginsberg. “We’re hopefully, in a very idealistic way, making the world a better place.”