Last November’s PACTESUR conference began with a moment of silence. The somber atmosphere was a reflection of our complex agenda: Creating safer and more inclusive cities. With our silence, we honored the memory of two policemen stabbed the previous week—one of them killed—in an attack by a radicalized Islamist on the streets of Brussels.

PACTESUR is an acronym for Protect Allied Cities Against Terrorism in Securing Urban Areas, and the Brussels conference marked the official conclusion of this European Union-funded initiative, which launched in 2019. The challenge for PACTESUR’s 14 partner cities was to answer the question: “How can cities protect their urban public spaces in the face of evolving threats, while ensuring they remain open and inclusive to all?” Local stakeholders, police, academics, and community representatives gathered at the conference to discuss years of research. For me, it was an opportunity to reflect on three years of teaching human-centered design in-novation at BESIGN, the Sustainable Design School, in Nice, France, and being part of this community of security-by-design experts.

“Security by design,” as defined by the Partnership on the Security of Public Spaces of the Urban Agenda for the European Commission, is an all-encompassing notion and new culture encouraged in European cities, to integrate city planning, urban architecture, street furniture, but also analysis of flows, detection techniques, and surveillance technologies. Based on the principles of urban resilience and quality of life, security by design aims to protect critical infrastructures and public spaces while making our cities safe and inclusive for all, and encouraging the coproduction of security.

At a time when decreased access to public space, terrorist threats and attacks, gender-based violence, and fraught police-citizen interactions sadly dominate our daily news, this long-term collaboration with major European cities helped me realize how much the idea of security in our public spaces exists at the intersection of ethical concerns, civic participation, the quality of urban life, environmental standards, and cultural values.

In 2019, I had just moved back to the South of France, where I grew up, after more than 20 years in New York. There, I had worked with New York Police Department Precinct 73 in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn on a community-centered project—a practice that values communities as experts and agents of their own lives. Conducted in collaboration with NYC Town & Gown and The School of Visual Arts during the summer of 2016, our Impact! Design for Social Change team devised Change the Story Brownsville, a communication strategy that aimed to build trust between the police department and the community of Brownsville. Inspired by the people’s precinct model first piloted in Los Angeles, which proposed that physical police stations offer a space for the community to gather, the project sought to build an inclusive, two-way, and analog communication channel. Back in Nice, I was happy to find a design home and joined BESIGN, which offered a dynamic setting for me to contribute and share my experience in New York.

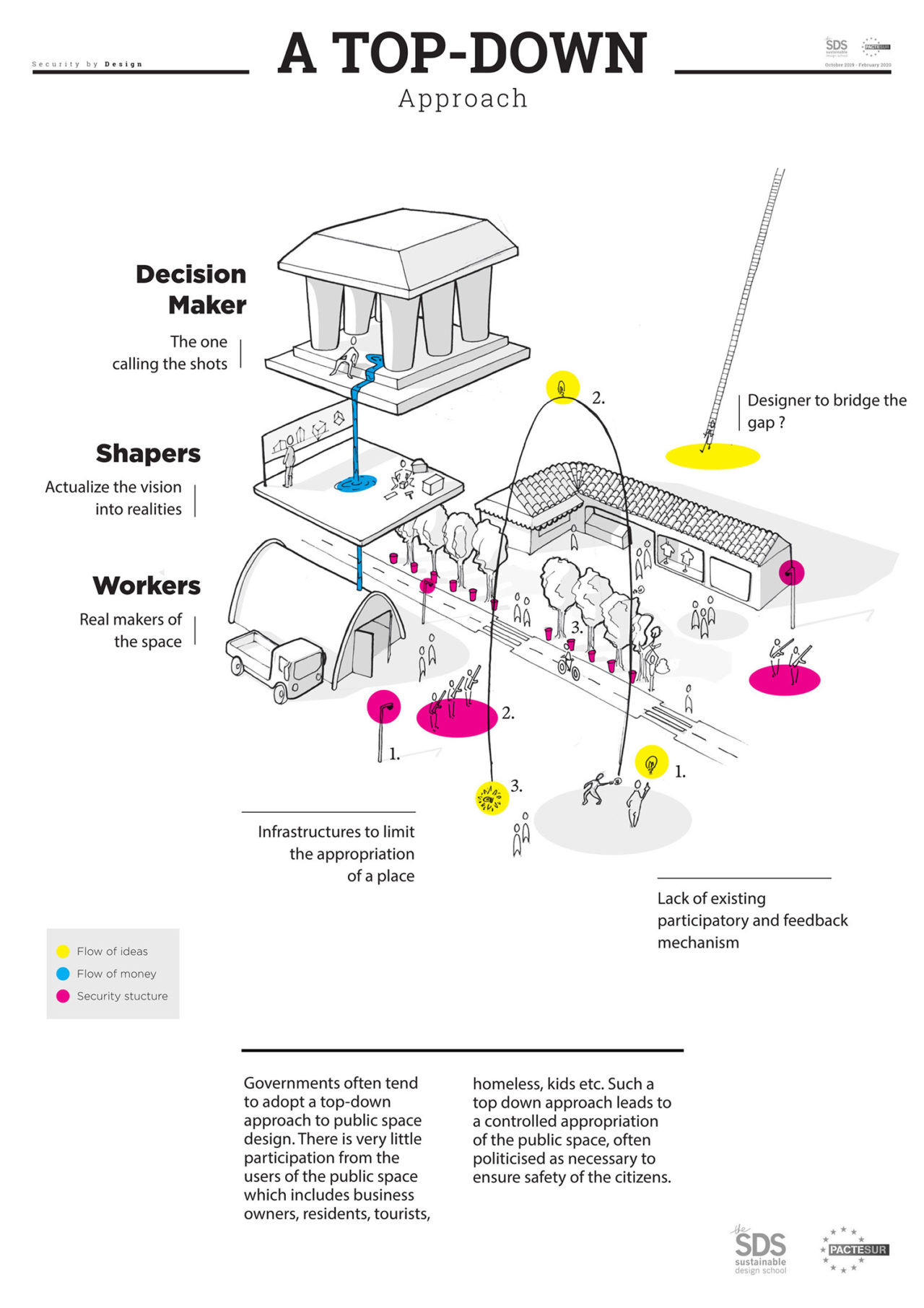

When The Métropole de Nice launched its PACTESUR project in 2019, it assembled multidisciplinary experts and reached out to BESIGN, which was uniquely positioned to help PACTESUR foster communication and citizen engagement in working towards safe, accessible cities. Shortly after the July 14, 2016, terrorist attack, in which 86 people were killed and another 434 injured when a truck drove into crowds of people celebrating Bastille Day, the mayor of Nice installed cabled barriers and heavy bollards along the UNESCO-designated Promenade des Anglais, where the attack took place. Although such site-hardening, as described by security experts, hasn’t proven to deter attacks, the city wanted to reassure its constituents. Now, they wanted to gain young designers’ perspectives on their solution. We had to work backwards, reimagining the space by and for tourists’ and locals’ use, keeping in mind the divisive aspect of securitization—a new word in my vocabulary since then.

My students were assigned to observe and analyze the freshly installed security equipment, to imagine new ways to integrate it in Nice’s seaside environment, and to provide creative, environmentally sound recommendations. A human-centered design approach (which, per the design consultancy IDEO, is about cultivating deep empathy with the people with whom you’re designing) seemed intuitively appealing to both my students and to Florence Cipolla, Nice’s municipal police chief engineer and a PACTESUR project coordinator. This approach was a big leap of faith for tech-driven security experts and municipal administrators like her.

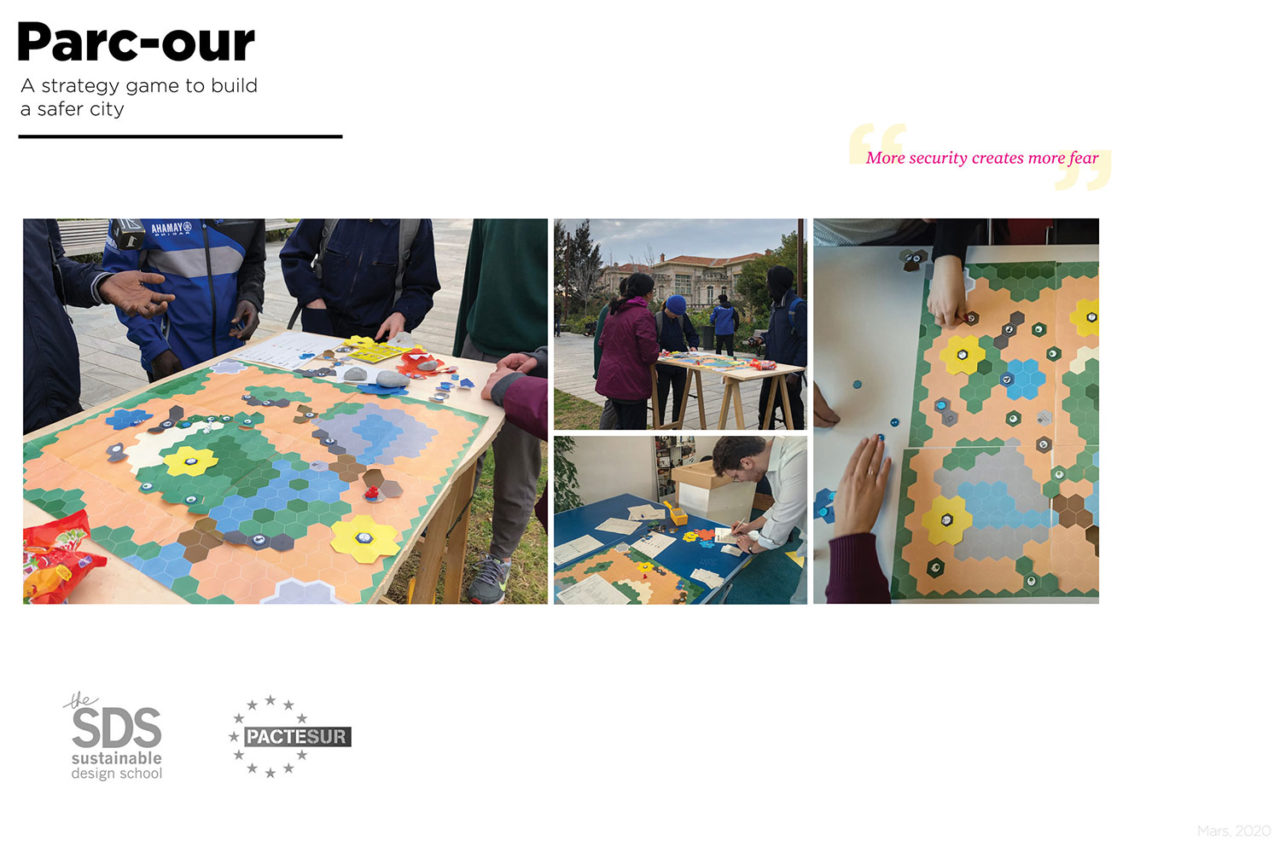

We used one of the United Nations’s sustainable development goals as our compass: “to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.” First, students devised interactive street interventions, board games, and citizen engagement strategies to debunk myths and shift perspectives about terrorism, beginning with the simple premise that the people affected by design should have a say in the design process. During the research phase that followed, we studied terrorism and its relationship to place and individuality, notions of liberty versus security, and the relevance of all this in the context of the 2016 attack. I encouraged these young designers to act as facilitators, using tools of empowerment and reflection to high-light the connection between the making of public space and our sense of safety.

The students’ interactive games, a project they dubbed “In/Pact,” engaged a diverse group of tourists, residents, and African migrants who tended to congregate on the eastern part of the promenade, to the dismay of the municipality. Most of these migrants had been victims of terrorism themselves; their stories and knowledge of Nice’s nooks and crannies provided a unique lived experience, yet our reaching out to them was perceived as off topic and inappropriate by our partners, who feared the politicization of our approach. This type of conversation is inherent in the work of human-centered designers involved in the security of cities, and one can only hope that as more of this type of collaboration takes place, stakeholders will become comfortable with truly holistic approaches, community engagement, and feedback.

Students also tested their game prototypes with local and international police gathered by PACTESUR. The atypical scenarios proposed in the students’ games enabled security experts to step out of their comfort zone and provide new perspectives on old problems. “Our role is not to create solutions, but to learn to ask questions, be open, and ‘unlearn’ our own assumptions,” wrote Arjun Rao, one of the project’s student-leaders.

Our In/Pact project taught us that monofunctional spaces were more prone to delinquency and insecurity. To encourage the use of public space, and make it safe, it’s important to promote a space that brings together varied activities; this functional mix will give rise to conviviality and attract citizens. The more visible and varied the activities, the more diverse the physical characteristics of a place, and the more secure it feels. The second phase of our project began in spring 2021. We again asked how design could better integrate security solutions with our cities, using Turin’s Piazza Veneto and Liège’s Place Saint Lambert as our new study sites. The idea of integration was one of the main insights we had gained from our work in Nice. Unable to travel during the pandemic, we tried to “meet” as many stakeholders as possible via Zoom—Italian and Belgian architects, designers, criminologists, residents, urban lab directors, police-force, representatives, psychologists, and prevention educators.

“Project Citiz,” as the second group of BESIGN students called our Turin and Liège project, also started from deep inquiry. How do we avoid the “bunkerization” effect—i.e. the risk of over-securing and fortifying public spaces to the point of making them unwelcoming. Should security be included in civic education? Shouldn’t the emphasis be placed on preventive strategies? Should security be more proactively debated among citizens and openly discussed with police? What are the explicit risks of managing heavy crowds? These questions underpinned our discovery phase until students created design solutions organized around simple actions: be informed, notify, act, and commit yourself.

“Project Citiz” consisted of four complementary solutions. The first element, a graphic installation on pavement, was meant to reappropriate the iconic Piazza Veneto (one of the largest squares in Europe), address crime prevention, and trigger informal public conversations. Secondly, the app facilitated alerting the police in case of danger, and a geolocated bracelet responded to crowd management challenges that the police had faced in these open plazas, where public events, concerts, and football game celebrations had been held—sometimes leading to deadly stampedes. Finally, a physical shield barrier system offered a highly functional and visually pleasing alternative to ad hoc protection barriers cities use for such large events. The easily deployable barrier was particularly appreciated by security experts, who praised its potential for greater visual homogeneity and legibility of the space in crowd management situations, while pointing to the poor catalogue of urban furniture available in the security industry altogether.

Over the past 30-plus years, the European Forum for Urban Security (EFUS) has built a dynamic community of international and interdisciplinary experts, aggregating knowledge and tools to better protect public spaces, define security best practices, and lobby for innovative and inclusive policy at the European Commission. The intellectual framework provided by those conferences has allowed for a rich reflection on my developing teaching practice and our ongoing findings, and a regular time to discuss “the problem of urban security, which is complex and not just about policing,” notes Elizabeth Johnston, executive director of EFUS. As I was shaping my course, grounded in a deep belief that practical, experiential learning is the way to go, I was also exemplifying the BESIGN school’s values of learning by doing. My design practice has been intuitively shaped by an empirical boots-on-the-ground method, though I still aim to dig deeper in the founding principles of great American public philosopher John Dewey, who considered social interactions, debates, and experiential learning the fundamentals of a good education and a working democracy.

Today, security by design is a highly technical pursuit, involving countless professions and industries. Equally valid is the point of view of the geographer who studies the social and spatial effects of the July 14 attack on the representation of the promenade; the urban anthropologist who questions freedom versus protection rights in Gdansk, Poland; the criminologist who explores the behavioral patterns of homegrown terrorists in England; the social worker who specializes in radicalization prevention in Belgium; as well as the traditional crime-prevention experts like the police and other municipal agencies. Together, EFUS and the PACTESUR project are fostering a safe, humanistic space for potentially polarizing conversations, wherein multiple stakeholders, including elected officials, can confront myriad perspectives, and, we hope, learn from each other and from new research and debates.

EVALUATING SOCIAL CHANGE

Regardless of how highly technical the question of urban security remains, and how ubiquitous high-tech surveillance devices have become in our lives, what matters most, I believe, is for the designer to “shift from being the custodian of fear to the custodian of safety,” as noted by Barbara Holtmann, crime and violence prevention leader and founder of Fixed in South Africa. If we adopt a perspective of trust and shared interests that considers the feeling of insecurity as seriously as the crime itself, then we start from a more inclusive ethos that can lead to community cohesion over suspicion. Our work as designers has often been to debunk myths. I believe sustainable designers should nurture their ethical responsibility by always evaluating the intention and success of their creative, human-centered design solutions. We’ve learned that security is complex and not just about policing. Making safe spaces is not just the job of law enforcement, but also of artists, urban planners, and local citizens. As security experts start to hear diverse perspectives on urban safety, the work for designers as agents of change has just begun.

In/Pact BESIGN Student Team (2019-2020)

Mathieu Andries, Holly L. Bartley, Maxime Chef, Julian Coiffard, Enzo Jamois, Tarushee Mehra, Sacha Nouviale, Arjun Rao, Fanny Ricciardi, Matthew Slack Stefani Takac, Tristan Terrusse, Nicolas Thomas, Agatha Verlay

Project Citiz BESIGN Student Team (2021)

Jules Baudrand, Owen Cartau, Romain Desrez, Juliette Dunand, Marine Jean, Lola Mangot, Clément Pheulpin, Pauline Poirot, Noémie Rocheteau, Manon Roulant, Baptiste Viot, Emma Weber

Bold = Fourth-year student leaders

LAETITIA WOLFF is a design strategist and curator, and the former director of strategic initiatives at the American Institute of Graphic Arts. She currently works as a design innovation consultant for organizations and municipal governments. She teaches impact design strategy at BESIGN The Sustainable Design School in Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, and at her alma mater, Sciences Po, in Paris. She is based in Nice, France.