by: Julia Adams

From redefining and defending borders to establishing a national image and politics, the former countries of the USSR are negotiating their independence as nations in the global capitalist economy. On 11.06.14, “New Kids on the Bloc: American Architects Working in Post-Soviet Culture Sectors” shed light on the current relationship between architecture and national culture, economy, and social climate in three heterogeneous countries: Kazakhstan, Bulgaria, and Poland. Empires have come and gone, leaving their traces in architecture. After stating independence, how does a postcolonial country establish a national architecture? What is an American architect’s place in a postcolonial and post-socialist country? Three American architects addressed these questions as they presented recent designs.

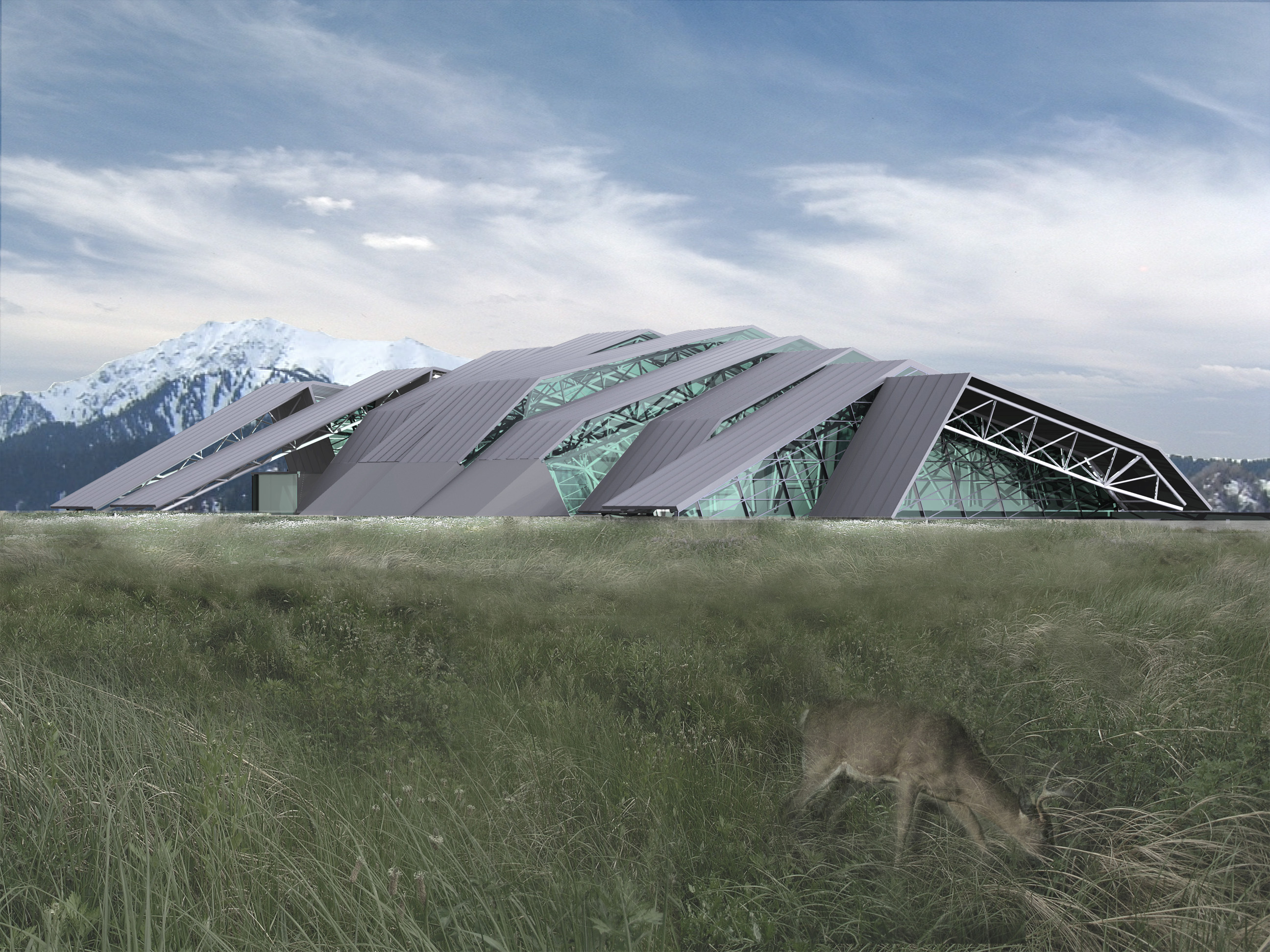

Audrey Matlock, FAIA, principal of Audrey Matlock Architects, presented Medeu Sports Center, located on a plateau in the virgin woods near Almaty, Kazakhstan. The center, comprised of tennis courts, a spa, and a skating rink, is a mile from the home of the project’s client, a Kazakh developer whose considerable residence was also designed by Matlock. She described a top-down approach, creating what her client, a wealthy, well-traveled, unnamed archi-phile wanted: high-design and high-end materials that could not be found within Kazakhstan. According to Matlock, Kazakhstan lacks the schools to provide locals with the tools to construct high-quality buildings, remarking that the architecture built during and since the Soviet reign is “abysmal” and “falling apart.” Matlock felt she brought new skills to local workers. When her team first started, they were unable to source steel from Kazakhstan; now the country fabricates steel, as well as white concrete.

Matlock’s final design is breathtaking: a shell made of a series of separated, bent, zinc bands that mirror the surrounding mountains. The center is embedded six feet underground so that the only visible structure is the mountainous shell. Overtime, the zinc bands will weather, blending into the environment. A country tour inspired Matlock to focus on the crown of the yurt for her design concept. The traditional structure is still a popular form of housing in Kazakhstan, and its crown, a symbol of peace and wellbeing, is a central architectural feature of a government building in Almaty and a prominent feature of the national emblem. Other features though, like the cantilevered structure and the separation of the steel bands, caused tension on site. In Matlock’s account, the word “concept” had no meaning for the local workers. To workers trained in engineer-driven architecture, the separation in the building structure was illogical, not artful; the populism of the yurt did not translate in the context of a high-design concept.

The design of Muzeiko, a children’s museum in Sofia, Bulgaria, by Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership (LHSA+DP), also takes inspiration from its immediate physical surroundings – the mountains. According to Lee H. Skolnick, FAIA, Bulgaria wants to build “Western-style, cutting-edge” buildings, but lacks the resources. While the country has rich and diverse architecture built by the Greeks, Romans, Ottomans, and, most recently, Soviets, said Skolnick, its contemporary buildings, often poorly built, falling apart, or unfinished, are overshadowed. While Skolnick’s firm provided Western design, he was intent on localizing the project, even saying that the firm was more interested in showing the local culture than locals were. his’s solution was to represent Bulgarian culture by sheathing each of the “peaks” in the material of an indigenous craft.

The America in Bulgaria Foundation, the organization behind Muzeiko, was created from a fund allocated by the U.S. Congress after Soviet dissolution to encourage the development of democracy and the free market. The foundation’s board decided that a children’s museum was a perfect “American export” that could also serve to augment a weak education system by informal means. Jo Ann Secor, a principal at LHSA+DP, mentioned that the local Bulgarians requested a focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education; the team, split American and Bulgarian, has been working with local scientists to best translate the museum’s content for Bulgarian children. The inviting, colorful interior, visible through a glass enclosure, is a symbolic contrast to the closed Soviet architecture. As Skolnick insisted, though, it was not the architecture that mattered most, but the content: “Nothing cultural was built in Bulgaria for 50 years. It’s not just that they’re buying Western design. They are buying Western experience.”

Thomas Phifer and Partners, recent winners of a competition to design the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Poland, also drew on glass as a symbol of transparency. Gabriel Smith, AIA, project director of the new theater and museum in Warsaw, discussed the dynamic contemporary arts scene in in the city, and the challenge of building adjacent to the Palace of Science and Culture. Completed in 1955, the same year as Mies’s Crown Hall at IIT in Chicago and Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, it is still the tallest building in Poland, and a symbol of socialist realism and Soviet dominance. Standing in sharp contrast to the Soviet power-tower, the broad museum and theater are completely visible from outside. A large public space separates the two buildings, designed for parties and other uses. Smith described the firm’s work as very much in service of the vibrant art scene in Warsaw, a facilitator of culture.

Working in Warsaw, often called “the new Berlin,” is not comparable to building in the forests of Alteny, Kazakhstan. Poland profits from its proximity to the West, and Germany in particular. By the end of World War II, 85% of Warsaw was demolished; the Polish rebuilt the city, honing impressive design and construction skills. Still, Smith has encountered, like Skolnick and Matlock, a fervent belief in limitations: “’This is impossible’ always came back and time and again, there’s a problem,” but, Smith said, “We’re Americans. We’re idiots. We think we can do anything.” Skolnick experienced a similar mentality: “It’s not possible,” was a phrase he heard often, continuing, “How many empires ran through [Bulgaria], there’s a sense nothing good or perfect can happen. We are crazy optimists, and we’re very proud of the things that they thought were impossible.”

Julia Adams is a Public Information Assistant at the Center for Architecture.

Event: New Kids on the Bloc: American Architects Working in Post-Soviet Culture Sectors

Location: Center for Architecture, 11.06.14

Speakers: Lee H. Skolnick, FAIA, Principal, Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership; Audrey Matlock, FAIA, Principal, Audrey Matlock Architect; Gabriel Smith, AIA, Director, Thomas Phifer and Partners; and Katie Gerfen, Executive Editor, Design, Architect magazine

Organizers: AIANY Cultural Facilities Committee

Sponsors: Kubik Maltbie