by: Bill Millard

The contribution of school facilities to the quality of education is difficult to determine, not only because so many other variables affect a school’s performance (faculty and parental input, students’ varying backgrounds, general societal change), but because education itself resists easily communicable metrics. As the animated debate at this daylong symposium suggested, continual improvement in the design of buildings, classrooms, and equipment remains a high priority for architects, educators, and the officials of extracurricular institutions.

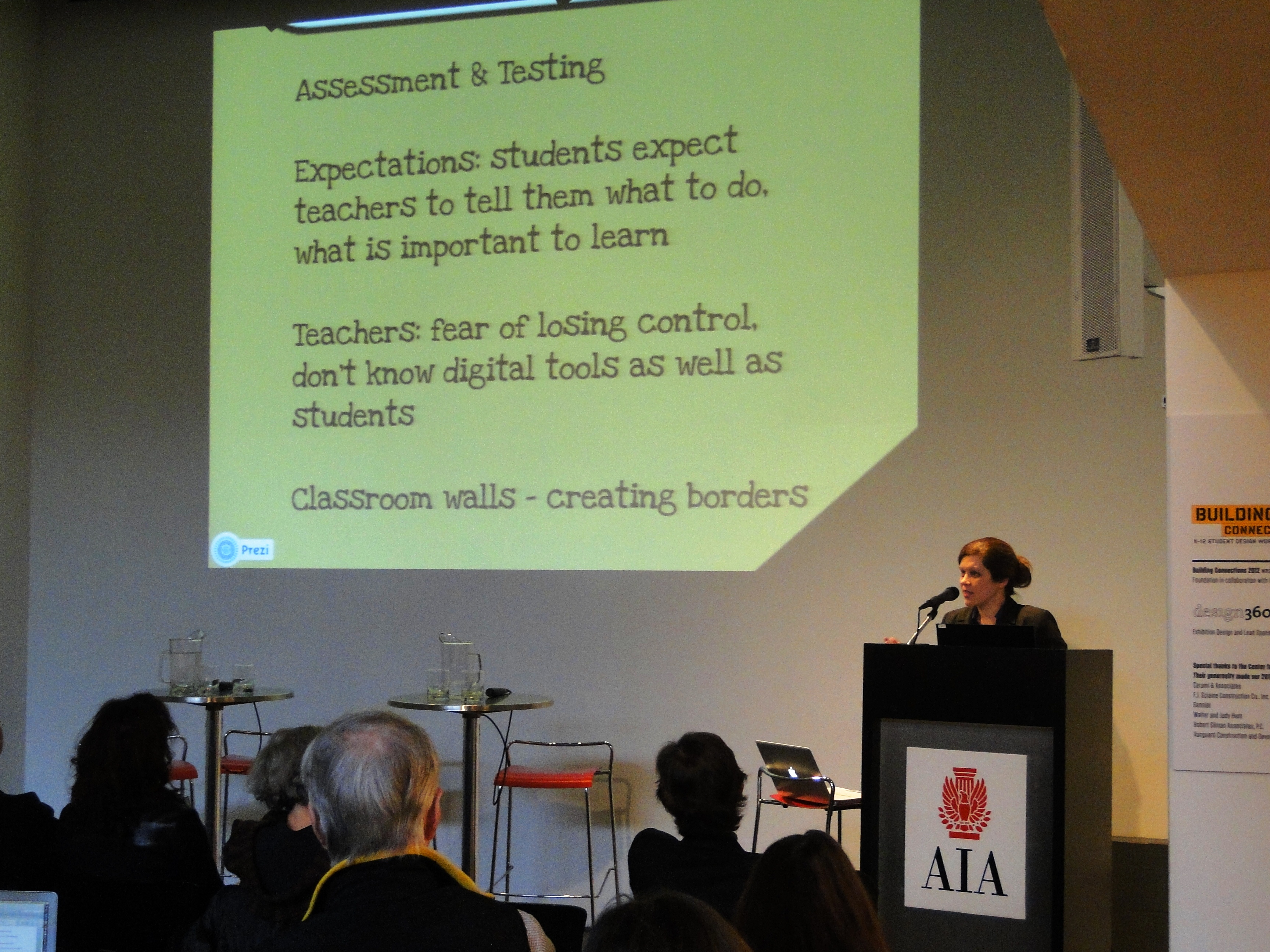

Such improvement runs up against institutional obstacles. For example, participants consistently critiqued various aspects of the educational system, particularly the narrowing effects of its assessment component on classroom practice (teaching aimed at the SATs or the Regents Exam, not the student’s broader well-being), and the reliance on spatiotemporal models rooted in agrarian or industrial assumptions (the nine-month academic year, the double-loaded corridor of standardized classrooms). Among many pithy quotations arising during the event, one observation by Einstein – invoked by Allen-Stevenson School headmaster David Trower – resonated with many listeners’ experience: “It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.”

The participants all work with and within these institutions to remake American education in ways that cultivate students’ natural curiosity instead of stifling it. Despite the legacies that remain obstacles to progress and the more corrosive effects of new technology, “The Edgeless School” exhibition curator Thomas Mellins argued that today’s teachers and designers are developing a progressive fusion of technology, architecture, and pedagogic philosophy to advance John Dewey’s dream of an education appropriate to life in a democracy. The present is a watershed moment, Mellins and others observed, when schools have the chance either to make the most of the generational changes catalyzed by information technology or to lose essential practices, even core principles, through a failure to understand those changes.

Sage and Coombe’s front-window installation, with yesterday’s orderly grid of identically oriented desks hovering above a more fluid and flexible contemporary learning space with Steelcase’s rolling, swiveling Node chairs and a Smartboard, visually communicates the symposium’s organizing premise: that today’s students, “digital natives” who have always lived in a wired atmosphere, thrive in physical environments different from the ones where earlier generations did their learning.

MIT developmental psychologist Edith Ackermann, Ph.D., provided much of the theoretical foundation for the later discussions and case studies, describing the need to “focus on the whole child, including [his or her] well-being, creativity, and ethos in addition to smarts, skills, and savvy, in and out of school.” Noting how social attachment, motivation, autonomy, art, play, and industriousness are linked, and following Howard Gardner’s observations that children’s styles of learning vary across sets of categories (patterners vs. dramatists, introverts vs. extroverts, or a four-way categorization used by Lego toy designers: “improvisers, dreamers, energy balls, and strategists”), Ackermann welcomed the new forms of literacy that digital-native generations bring to their environments, and urged educators to be open to adapting those environments accordingly. Steelcase’s Lennie Scott-Webber later extended this theme, drawing on brain science to argue that “kinesthetic learners,” who need movement and touch to acquire knowledge, are too often disadvantaged relative to visual or aural learners, with the implication that “buns in seats, a business model” and the lecture-hall format (“stand and deliver” for a single speaker, “sit and get” for passive listeners) should be replaced by diverse spaces and practices that make learning a more active process.

Counterbalancing Ackermann’s embrace of emerging modes of communication was Dr. Geraldine Summa’s experience in the trenches of a pediatric medical practice in New Jersey, where she increasingly sees young patients with serious symptoms associated with media overuse, from orthopedic injuries involving positioning and repetitive joint movements to disorders in attention, sleep, nutrition, and interpersonal relations. The grail in the ed-tech domain, the speakers agreed, is a balanced involvement with information media so that they do not crowd out the rest of life. “The more we are nomadic,” Ackermann noted, “the more we need anchor points; the more things get dematerialized, the more the physical space counts.”

School is increasingly merging with the non-school world, and several case studies showed imaginative ways of activating young minds beyond conventional classrooms. The new National Museum of Mathematics (MoMath), in particular, brings a heady range of gadgets, displays, objects, and interactive environments into a tight site on 26th Street; four of its directors walked the audience through its rooms and features in an upbeat tag-team keynote presentation. “Most people don’t associate the word ‘fun’ with the word ‘math,’” said associate director Cindy Lawrence, “and so if people come to a place that’s called math, and they leave and they say they had fun, to us that’s the ultimate success with our exhibits.”

The recently-opened MoMath (Museum of Mathematics) is quickly proving that its fun aspects can engage visiting students with the underlying concepts – particularly in geometry, an area of math conducive to attention-grabbing physical illustration. Executive Director Glen Whitney recalled how one eight-year-old, while playing with a set of interactive objects, independently built a rhomibicuboctahedron, a complex symmetric shape classified among the Archimedean solids. Another young visitor’s facial expression captured on camera said most of what needs saying about the hedonism at the core of learning. Amid all the abstraction and urgency of purpose that inevitably pervade educational discourse, such concrete expressions were breaths of fresh air.

The implications of advances in pedagogic theory for architecture and furniture design are clear in some areas – spaces and surfaces with integrated infotech; an emphasis on mobility, modularity, and customization over the static and the standardized – and more speculative in others. Historical overviews of educational facilities contributed sobering perspectives on past experiments and panaceas: in the 1980s, recalled Douglas Hassebroek, AIA, of Butler Rogers Baskett, “we thought everybody in schools would just be watching TV all day,” before ubiquitous video monitors joined mimeograph machines, filmstrips, and overhead projectors on the scrap heap of ed-tech history. Other innovations like the Froebel Gifts and the open Montessori classroom have weathered historical phases somewhat better, Hassebroek noted, and tomorrow’s most reliable advances are likely to draw from those examples, but when the ed-tech industry tries to keep pace with consumer electronics like Apple’s iPad, “we just get lapped.”

With more information reaching students through widely distributed channels such as mobile phones and laptops rather than the traditional point sources of the teacher and the textbook, the component of schools most in need of fundamental rethinking is often the library. Dennis Cohen of Ralph Appelbaum Associates presented the Learning Curve project for the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library, an American Library Association “Library of the Future” whose Saarinen-esque forms were inspired in part by the Men in Black film’s alien-control headquarters. Its features include a central Information Vortex, distributed “base camp” stations, stacks forming acoustical boundaries defining spaces organized around stages of lifelong learning, ovoid individual privacy pods, and mobile informatics guides using their own original tools developed on an open-source basis. Using a series of case studies, Jennifer Sage, AIA, contrasted one poignantly underused school library with other spaces that blend bookshelves with laptop drawers, hybridize the library and the media lab, or offer students outdoor learning areas resembling a college quad (a helpful motivator in Harlem’s Democracy Prep, a charter-school network that guides students from all backgrounds toward high performance and college admission).

The best synergies between teaching and technology, Trower suggested, occur with a clear awareness of how the tech affects the balance between the mental functions that Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman identified in Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011): quick, intuitive emotional reactions and more deliberate applications of analytic logic. “Thinking about technology and its pervasive, sometimes almost pernicious pull at us,” Trower commented, “we mistake the rapid information that technology provides for good learning, for knowledge, for wisdom, or even for truth.” The echo of T. S. Eliot’s much-quoted lines from “The Rock” (“Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?”) implies that good old analog-era humanistic qualities like judgment, humor, sociability, and a sense of mind/body balance will continue to anchor the design and teaching professions’ efforts to reconfigure their spaces to keep students afloat amid the rising tide of raw data.

Event: The Edgeless School: Designing for Learning in the Digital Age

Location: Center for Architecture, 01.19.2013

Speakers: Thomas Mellins, Curator, The Edgeless School (moderator); Edith Ackermann, Ph.D., Visiting Scientist, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Honorary Professor of Developmental Psychology, University of Aix-Marseille; Dr. Gerri Summa, Summit Medical Group, Warren, NJ; Glen Whitney, Executive Director, Cindy Lawrence, Associate Director & Chief of Operations, Tim Nissen, Chief of Design, and Ben Levitt, Chief of Education, National Museum of Mathematics (keynote presentation); David Trower, Headmaster, The Allen-Stevenson School; Laura Hollis, Director of Technology, Saddle River Day School; Douglas Hassebroek, AIA, Associate Partner, Butler Rogers Baskett Architects; Dan O’Keefe, Curriculum Designer, Mission Lab, Institute of Play; Jake Barton, Principal, Local Projects; Jennifer Sage, AIA, Sage and Coombe Architects (panelist and introduction); Lennie Scott-Webber, Ph.D., Director of Education Environments, Steelcase; Dennis Cohen, Project Director, Ralph Appelbaum Associates

Organizers: AIANY in collaboration with the Center for Architecture Foundation

Sponsors: Duggal Visual Solutions, Hyperakt, Shaw Contract Group, Waldners Business Developments (underwriters); Avery Dennison, MechoSystems, Swanke Hayden Connell Architects (patrons); Ennead Architects, F.J. Sciame Construction, Levien & Company, Beyer Blinder Belle, Forest City Ratner Companies, Mancini Duffy|TSC, New York City School Construction Authority, Perkins Eastman, STV Group, Thornton Tomasetti (sponsors); Bonetti/Kozerski, Lutron Electronics, Turner Construction Company, ASSA ABLOY, Cameron Engineering, Cosentini Associates, DeLaCour & Ferrara Architects, E-J Electric Installation Co., Ennead Architects, F.J. Sciame Construction Co., FXFOWLE Architects, Ingersoll Rand Security Technologies, Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & Bertolotti, Jack Resnick & Sons, JAM Consultants, JLS Industries, Knoll, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, Langan Engineering and Environmental Services, Lend Lease, Milrose Consultants, Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects, Syska Hennessy Group, Vanguard Construction & Development Co., Viridian Energy & Environmental / Israel Berger and Associates, World Trade Center Properties (supporters)