In the spring of 2021, a sea of insulated delivery bags, neon vests, and protest signs flooded Manhattan. Chants like “Essential Workers, Not Disposable,” “Tips Aren’t Salaries,” and “Justice for Deliveristas!” echoed down Broadway and culminated at City Hall. Organized by Los Deliveristas Unidos—a coalition of immigrant, app-based delivery workers within the Worker’s Justice Project (WJP)—the mobilization marked a turning point. The workers who had kept New York running during the pandemic were now demanding dignity, safety, and basic labor rights. That day, workers, organizers, and designers collectively began asking: What would it take to build dignified infrastructure for people who keep the city moving—yet remain excluded from its design?

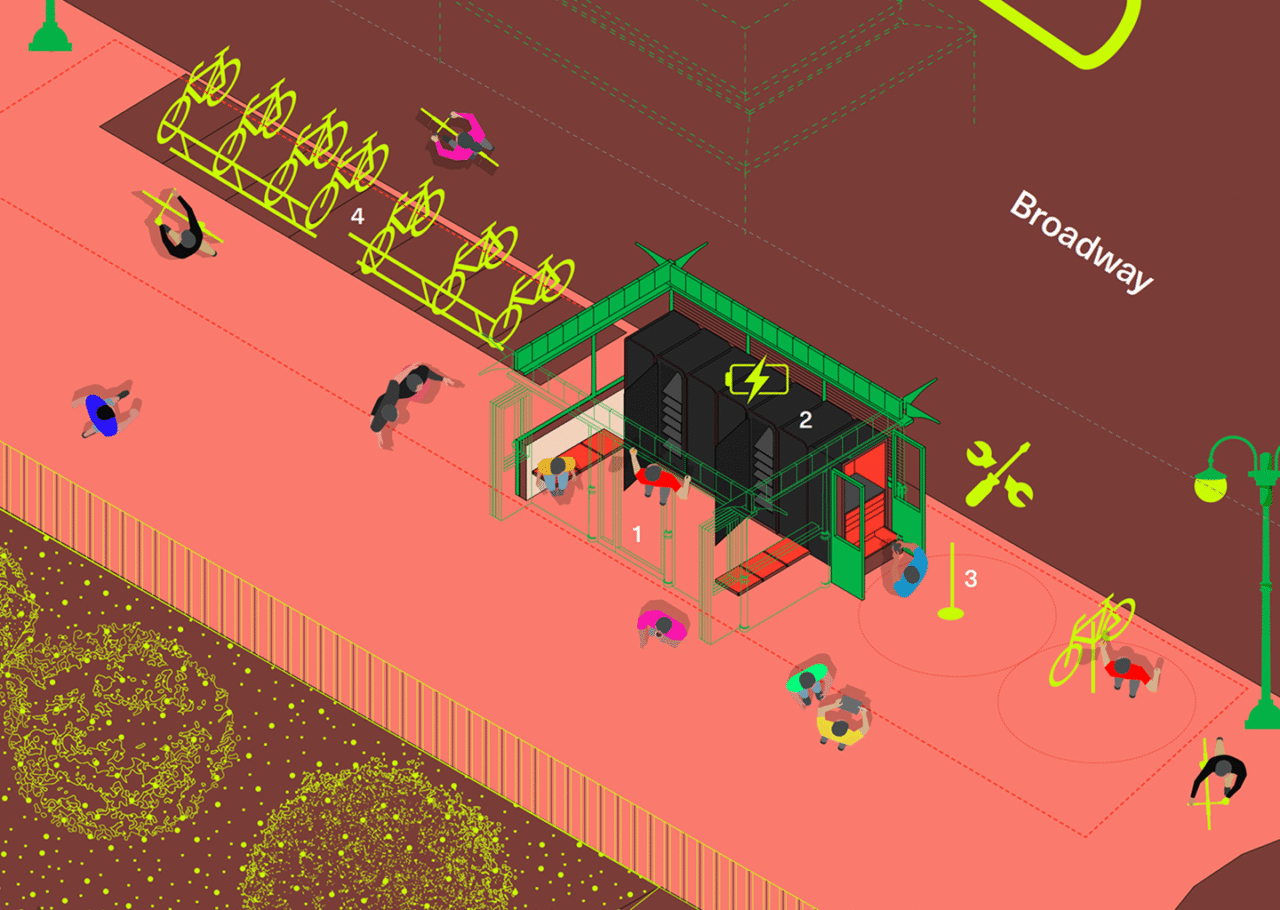

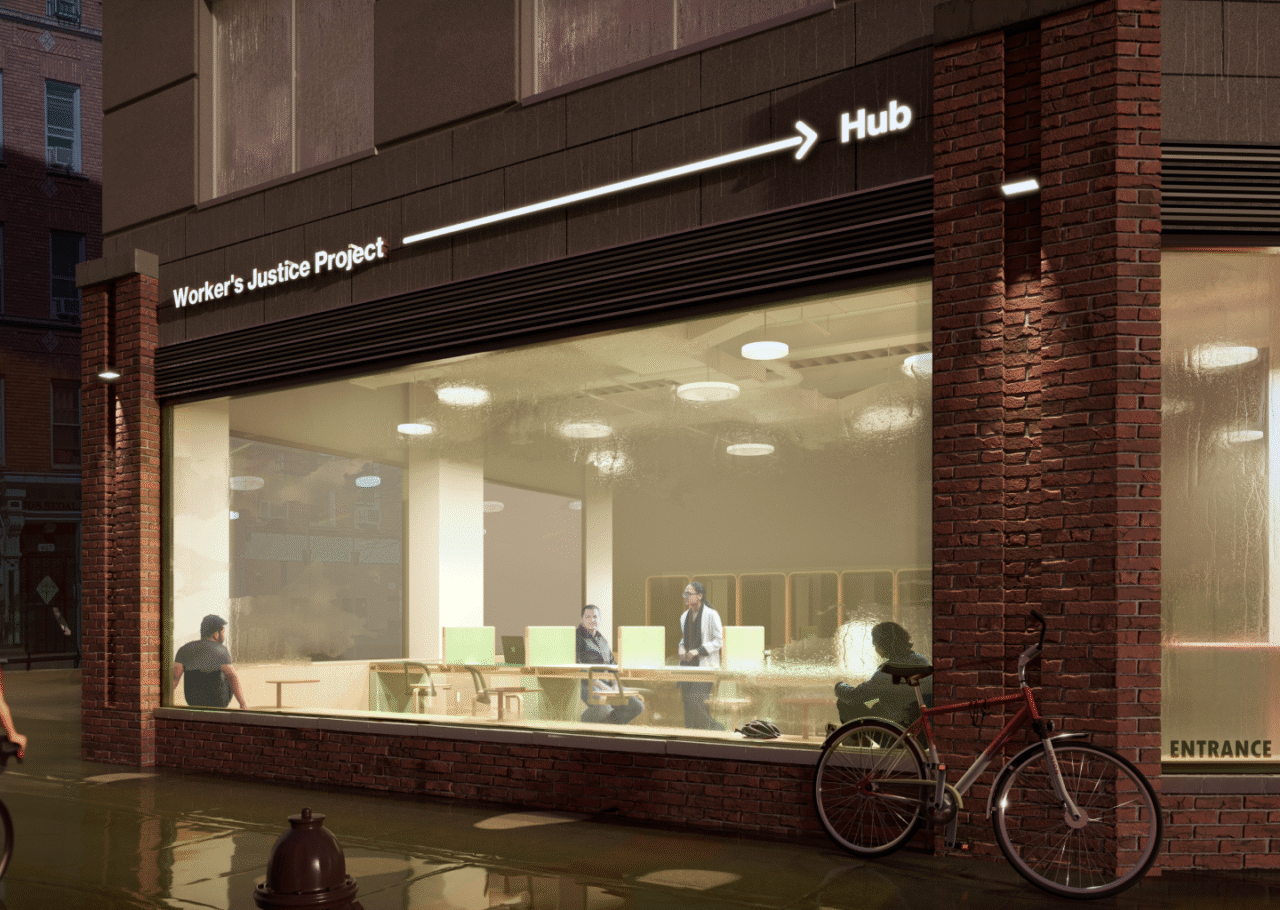

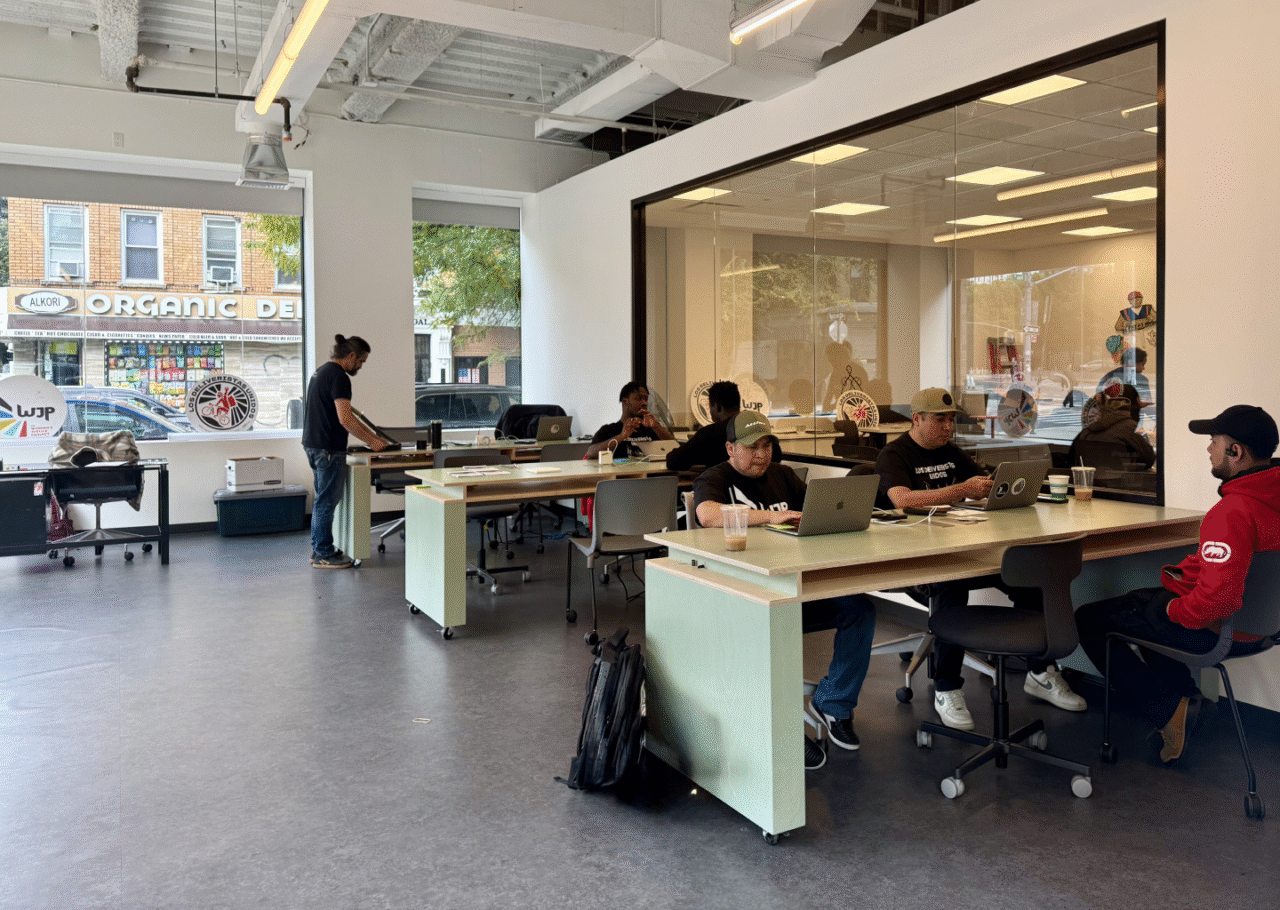

Over the past several years, I’ve collaborated with WJP and its community of workers, staff, and advocates to conceptualize and implement the Hub Network: a series of worker-led havens for day laborers and gig workers in New York City. The first two hubs opened last summer in Williamsburg and South Slope, Brooklyn. They provide shelter, restrooms, training and rights-awareness programs, and case management for wage theft, unjust deactivations, and labor violations. These first-of-their-kind spaces respond to a glaring absence of infrastructure for workers whose workplaces are the streets.

My path into this work began long before 2021. Shortly after moving from Mexico City to New York more than a decade ago, I noticed a group of women standing for hours at the intersection of Division and Marcy avenues in South Williamsburg—in the bitter cold of winter and under the scorching summer sun. One morning, after overhearing Spanish, I greeted one of them, “Buenos días.” She introduced me to the hiring corner known as La Parada. That brief exchange pushed me to investigate how women day laborers endured precarity, exposure, and marginalization, and whether design could offer support.

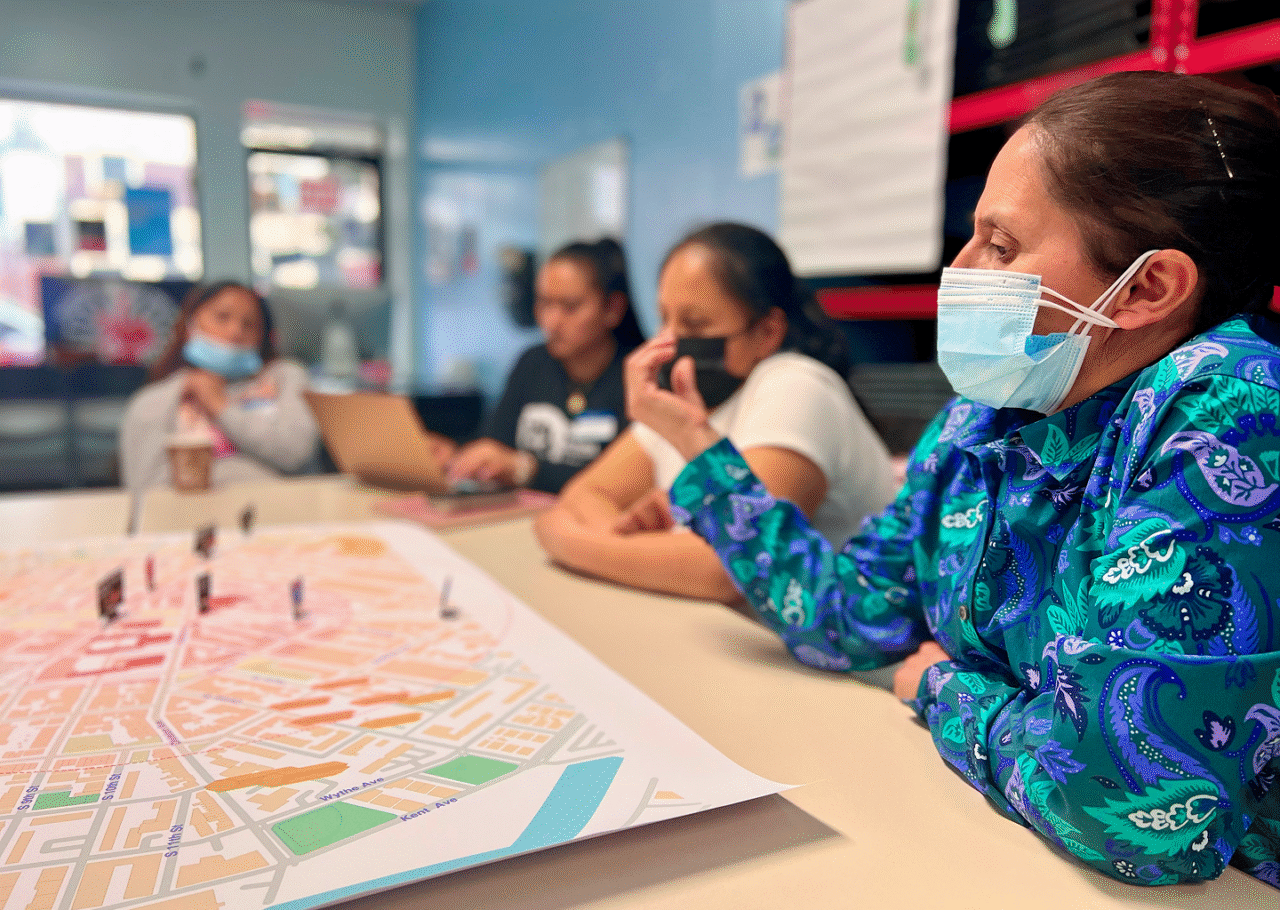

This inquiry led me to WJP, a small but fierce non-profit that has organized low wage immigrant workers for more than 15 years. The group had already created a modest center nearby and, after Hurricane Sandy, even repurposed a shipping container into a temporary micro-center for construction day laborers helping to rebuild the city. With support from a New York State Council on the Arts independent design grant, I began a Participatory Action Research project with WJP and the women of La Parada. Together, we mapped neighborhood resources, raised awareness about safety and workers’ rights, and—most importantly—imagined alternatives to their unsafe hiring site. We imagined a dignified workers’ center.

The pandemic brought new urgency. App-based delivery workers, similarly unprotected, flooded WJP, seeking support. In response to the needs of both day laborers and gig workers, we conceived the Hub Network: a set of centers across the city offering dignity, rest, legal support, and community for cleaning, construction, and delivery workers.

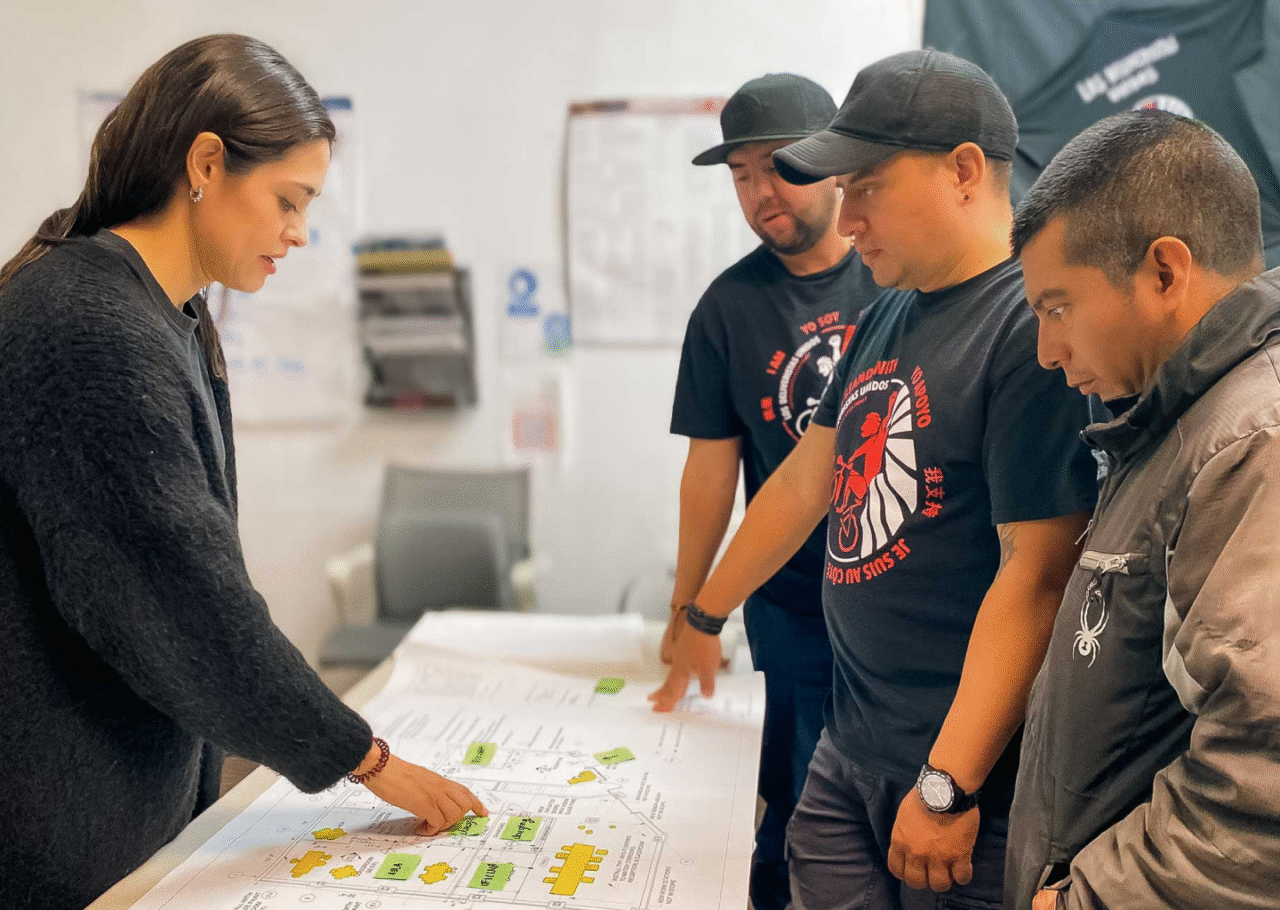

As a young grassroots organization, WJP had no realistic path to buying or developing property. So we pursued another approach: leasing a long-vacant storefront and transforming it into a functional, culturally meaningful space shaped directly by the workers who would use it. Workers and organizers participated in site selection, programming, and design. My role was to facilitate dialogue, guide decisionmaking, test scenarios, and translate lived experience into spatial form. My team and I were not merely drawing plans. We were listening, centering workers’ needs, and creating a space rooted in their realities: unpredictable schedules, wage instability, lack of institutional support, and cultural and linguistic isolation. What began at a sidewalk corner has become a collaborative design movement—workers shaping spaces that honor their labor, creativity, and humanity.

Working with organizations like the WJP and New Immigrant Community Empowerment has shown me how architects can play a transformative role by listening, co-creating, and learning from the daily practices of activists and organizers. When we center design justice, architecture becomes a form of activism—a practical, everyday intervention. It is true that architecture cannot, on its own, resolve the systemic inequities that shape labor, immigration, and public policy. But it can materially shift how people experience the city today. When architects work alongside our most vulnerable communities, design becomes a tool for accountability and collective power.

As we confront rising housing costs, eroding public space, and widening precarity, architects have a particular role to play. We understand how space distributes dignity, opportunity, safety, and access. Every design choice can—and must—be a tool for social transformation and a step toward more just, livable futures.