Today we take for granted that dense urban living is less resource-intensive and therefore greener than its rural and suburban counterparts. Indeed, the average New Yorker is responsible for roughly one-third of the carbon emissions of the average American, according to the 2015 Inventory of New York City Greenhouse Gas Emissions. This is due largely to pervasive public transportation and small apartments with shared walls that insulate one another. Moreover, cities are beginning to supersede state and national governments as the creative cauldrons of effective, large-scale environmental policies.

The innate greenness of cities is now so broadly accepted that it’s hard to remember that not too long ago, everyone believed the exact opposite. Cities were decadent, polluted, and artificial, and the countryside was wholesome, clean, and natural, as exemplified in two comments by Frank Lloyd Wright: “To look at the cross-section of any plan of a big city is to look at something like the section of a fibrous tumor” and “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.”

This is the little-known story of how New York City architects and their enlightened clients, eventually supported by city and state officials, inverted that paradigm, brought the environment into the city, and scaled sustainability over the course of three decades.

Back in the 1970s, New York City was moving toward a crisis point that overtly exposed its highly toxic environment. Along with its economic and social woes, the city was an environmental catastrophe. Its air was filthy due to coal- and oil-burning furnaces, waste-burning incinerators, and vehicles without emissions controls, and its great harbor was fouled by the dumping of raw sewage nearby at sea. At that point, it would have been hard to imagine that cities—particularly traditional dense cities—had environmental benefits.

Many New Yorkers embraced the countercultural movements of the late ’60s and ’70s and looked outside urban areas for a greener alternative. In America’s great transcendentalist tradition, they renounced city life, joined back-to-the-land communes, and cultivated rural self-reliance. Out of this individualistic, off-the-grid strain of the counterculture came many of the first experiments in green buildings, typically small passive solar houses, often based on vernacular models and constructed of natural materials. The era’s bible, The Whole Earth Catalog, featured low-energy houses made of rammed earth and straw bales—technologies that would have been decidedly out of place in a dense urban environment like, say, Times Square. Tinged with a rural utopianism, these early experiments seemed inapplicable and therefore irrelevant to the vast building stock of the nation’s struggling cities.

Paradoxically, perhaps, the early 1960s also saw social activism that would help later generations rediscover the great strengths of cities. Jane Jacobs, the famous writer/activist, stood her ground when mainstream planners were plotting to demolish huge swaths of dense traditional neighborhoods and replace them with hygienic “towers in the park.” Her successful battles to save Lower Manhattan’s neighborhoods, including stopping Robert Moses’s plan for a four-lane highway through Washington Square Park, are rightly recognized as the turning point when people started to appreciate dense, disorderly cities again—at least enough to stop tearing them down. In line with this more progressive strain of urbanism came three small but revolutionary New York City architectural projects in the late ’80s and early ’90s demonstrating that cities, too, were part of the environment and green buildings could actually be a positive element for that environment.

THE ’80S & EARLY ’90S: FIRST GREEN STEPS

In New York, the ’80s began with a short-lived boom of tax-driven downtown office building development focused on costs, prepackaged solutions, and glitz. Green architecture had not yet entered the city or become part of institutional agendas. This was the period before the United Nation’s watershed Rio Sustainability Conference in 1992, AIA’s Committee on the Environment (COTE), the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), and LEED. Imagine, then, the excitement with which architects Randy Croxton and William McDonough greeted their respective commissions in the mid- to late ’80s for the design of the New York headquarters of three leading environmental organizations. All were to be green renovations that reused historic urban building stock rather than new glitz.

In the earliest of the three, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) offices required that William McDonough Architects design its space to strict air-quality requirements, an element of the commission that McDonough has credited with pushing him toward his lifelong investigation into healthy building materials and eventually leading to the “Cradle to Cradle” building materials rating system. Talking to the New York Times about the project after the fact in 1992, McDonough pointed out that the architecture team “avoided paints that have fungicides for shelf life” and “carpet glues with formaldehyde,” instead tacking down the carpet.

The progressive design philosophy applied to the EDF assignment (completed in 1986) was shared with developer David Gottfried, who, with lawyer Mike Italiano, was exploring the possibility of creating an organization that in 1993 became the USGBC. Notably, McDonough was among the handful of NYC-based architects to participate in the AIA’s COTE, which had been founded three years earlier. COTE played a critical role in launching USGBC, including providing some of its early board members and offering technical input crucial to the creation of the LEED rating system, now used in over 170 countries.

Another NYC architect who was actually a founding member of COTE was Randy Croxton. His and Kirsten Childs’s (Croxton Collaborative) design work for three floors of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s (NRDC) Lower Manhattan offices is cited in Gottfried’s 2014 history of the green building movement, Explosion Green, as monumentally influential in what later became LEED. The project, completed in 1988, addressed head-on the contemporaneous concern that “too much” energy efficiency could lead to “sick buildings” and insufficient fresh air. Their design accomplished ambitious energy-efficiency objectives while also ensuring the space had so much additional fresh air that Gottfried referred to a “gentle breeze” coming through the key spaces. Like McDonough’s design principles, Croxton’s lessons were codified into influential guidelines published in 1994 by the National Institute of Science and Technology.

Just as importantly, perhaps, the design also generated mainstream media coverage, including both a New York Times feature article and a follow-up Times editorial celebrating the building’s proven energy performance (“An Exemplary Office For Conservationists,” by David Dunlap on April 4, 1989, and “The Editorial Notebook; A Light Diet for Office Light,” by David C. Anderson on April 2, 1990).

The third initial catalyst for green urban architecture also came from the Croxton Collaborative. With their design for the National Audubon Society’s Varick Street headquarters, Croxton and Childs literally wrote the book on best practices in green architecture. The 1994 book-length case study titled Audubon House: Building the Environmentally Responsible Energy Efficient Office tells the detailed story of the $14 million renovation and recycling of George B. Post’s 1890 Romanesque gem. Most importantly from a policy standpoint, according to the AIA’s 1994 Guide to Sustainable Design, the architects and Audubon demonstrated through detailed analysis that if “all buildings followed its example for water conservation, solid waste management, and support for mass transit, then the next sewer module, incinerator, landfill, or highway project could be avoided.” As with earlier work, it also received substantial press attention, including a piece in the New York Times (“Beyond Organic Architecture: The Office as Oasis,” July 26, 1992).

NRDC HEADQUARTERS (1987–1989) BY CROXTON COLLABORATIVE

40 WEST 20TH STREET

In his 2014 book Explosion Green, David Gottfried, founder of the U.S. Green Building Council and a historian of the green building movement, concluded that the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) project was “likely the first sustainably designed office space in the country, addressing light, air, energy, and occupant health and productivity.” He points out that energy use in the office was “75% more efficient than the norm” and that “the level of fresh air supplied to the space was six times higher than required by the prevailing standard,” creating “a slight breeze.” Most importantly, a Con Edison study monitoring the performance of the space over the next 24 months demonstrated energy use had come in at .55 watts per square feet while producing staggering amounts of fresh air. These results were accomplished through the innovative layout, generous daylighting (possible in part by removing the existing dropped ceiling), and cutting-edge lighting design. In a New York Times article covering the project, architect Randy Croxton stressed the “off-the-shelf” nature of key components. “There is not one technological breakthrough here,” he told the Times. ”The individual pieces—like that lamp—anybody can buy. We didn’t invent it. But that combination, that assembled performance of the system in place, is unique.”

LATE ’90S, EARLY 2000S: GREEN DREAM TEAM

In the late ’90s, a dream team of incredibly well-positioned New York visionaries—developer Doug Durst, architect Fox & Fowle, and builder Dan Tishman, encouraged by environmental gadfly Ashok Gupta of the NRDC—made a startlingly gutsy move. They decided to take these nascent ideas to scale and create a green skyscraper right at 4 Times Square, the symbolic, gritty heart of the nation’s largest city. This move nailed it: green building was now big, bold, and brashly urban, and it caught everyone’s attention.

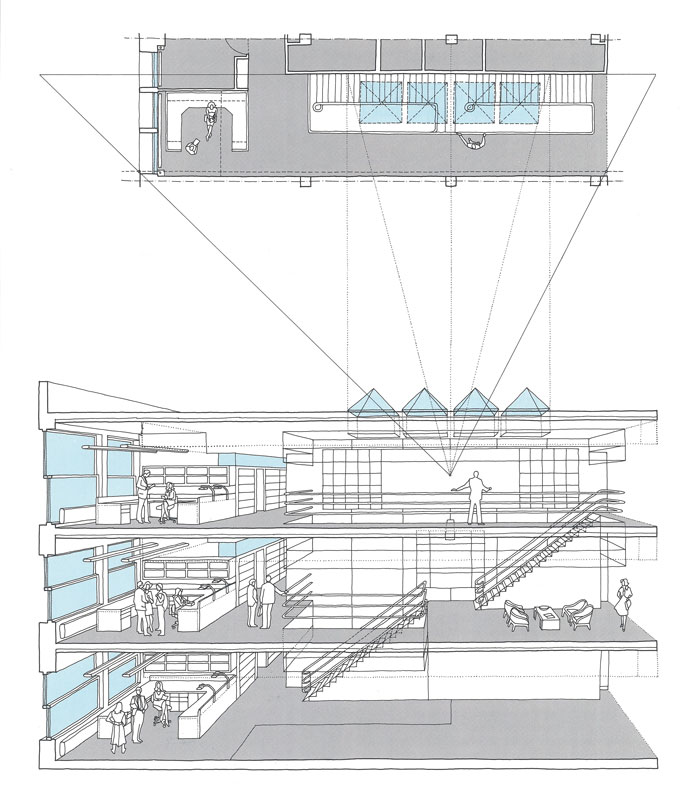

While 4 Times Square was under construction, Hilary Brown, FAIA, of the Department of Design and Construction (DDC), the city’s building agency, initiated the greening of municipal buildings by issuing the influential High Performance Building Guidelines (1999). Also taking lessons learned from 4 Times Square, Bob Fox guided a team of design luminaries in the development of green guidelines for New York State’s Battery Park City, an entirely new neighborhood. These latter guidelines helped create a wave of iconic private sector green buildings, including the first LEED-certified residential highrise, the Solaire by César Pelli, completed in 2003. And pursuant to the DDC guidelines, a series of municipal projects were completed in the mid-2000s, including Staten Island’s St. George Ferry Terminal—with its signature green roof—designed by HOK and completed in 2005, and the Queens Botanical Garden, designed by BKSK and completed in 2007.

Already in 2005, these public and privately commissioned designs had been so successful in demonstrating the benefits of green building that the city passed its first major green building ordinance, Local Law 86, which required most New York City government projects to meet LEED standards and reduce energy and water consumption. In just 15 years, sustainable design in New York City had leapt from a handful of artisanal renovations to strict requirements that affected every single large municipal project. Soon it would go citywide. By the 2000s, the city was growing rapidly and expecting a million more residents by 2030. How could they be accommodated while still maintaining quality of life in an already crowded city whose infrastructure shows signs of strain? Sustainable building design appeared to answer this question, and in 2006, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city launched a major planning effort involving key players from many of the projects discussed above. The result, the widely emulated PlaNYC, had 10 overarching goals, including access to parks, clean air, and a 30% reduction in citywide carbon emissions by 2030.

A key insight behind PlaNYC was the extent to which buildings dominate New York’s environmental footprint, with buildings being responsible for fully three-quarters of citywide carbon emissions. Consequently, PlaNYC included initiatives aimed at greening the city’s building codes and regulations and phasing out dirty residual heating oil, which has resulted in the city having its cleanest air in well over a decade. PlaNYC’s signature green building initiative, the Greener, Greater Buildings Plan, comprehensively addresses energy use in the large buildings that comprise half the city’s square footage by requiring benchmarking, audits, and submeters—providing building owners with the information they need to improve their buildings and manage them efficiently.

CONDE NAST BUILDING (1996-1999) BY FOX & FOWLE

4 TIMES SQUARE

The former Condé Nast Building, now known as 4 Times Square, was recognized even as it was being designed as a pioneering green skyscraper. Gas-fired absorption chillers and a high-performing insulating and shading curtain wall dramatically limited the need to heat or cool the building during much of the year. At the same time, the air-delivery system with high-elevation outside air intakes provided 50% more fresh air than was required by New York City Building Code. Green features also include high-performance windows; separate disposal chutes for recyclable materials; occupancy sensors; variable speed drive pumps; photovoltaic panels embedded in the upper walls of the building and two 200 kW natural gas-powered phosphoric acid fuel cells that provide about 10% of the building’s electricity; 100% outside air purge system; a floor-by-floor air-handling system; nontoxic and biodegradable materials; and sustainably harvested wood. The innovative rooftop structure known as “hat trusses” strengthen the building by tying together the vertical structural members, which reduces the tonnage of structural steel needed. As with the NRDC project, the client, the Durst Organization, was fearless in investing in a post-occupancy analysis of the building’s performance so it could learn from mistakes as well as successes.

KEEPING THE MOMENTUM ALIVE

After PlaNYC was rolled out, Mayor Bloomberg began to play a leadership role in the nascent low-carbon city movement, most recently serving as the UN’s Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change. By the time of the watershed Paris climate summit in 2015, less than 30 years after the first green office renovation, New York City and its key design and policy precedents had been instrumental in scaling green building globally.

Continuing recognition of the importance of environmental objectives is not a problem in New York. Mayor Bill de Blasio has committed to achieving even deeper carbon reductions than his predecessors (80% carbon emissions reductions by 2050). However, performance on this commitment will take more than political will—it will take technical sophistication and innovation. The city has mandated that its own new buildings become laboratories of just this kind of innovation, and the New York State Energy Research Development Authority is launching a competition for hyperefficient new multifamily buildings, which should further broaden the knowledge base. The hardest part remains motivating private sector owners to exploit the carbon reductions inherent in most of their—still highly inefficient—existing buildings. Benchmarking and audit data collected pursuant to the PlaNYC mandates is helping to rationally prioritize action. But, disappointingly, it is not proving a significant source of motivation for owners of existing buildings to undertake retrofits they continue to deem costly or simply irrelevant to their basic business models.

In the end, however, New York’s path toward deep carbon reductions will not just be top-down or regulatory in nature. Nor will it come just from improved technologies and education. We will need more pioneering clients and architects like those of 30 years ago, whose individual project blueprints ultimately became blueprints for a better city.