I binge-watched The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix recently, and I can’t stop thinking about it.

It’s not because I follow chess per se, but because I think there’s something valuable to be learned from the way the series portrays teamwork as the driving force behind the success of an individual. Every time a chess player—the American lead character or a Soviet opponent—wins a game in this series, news cameras flash on the winner, and magazines report the triumph. But we in the audience see that there’s a network of friends and friendly competitors who have been researching past games and advising the player on strategy and “gambits” all along. One reason that Russia has long been dominant in chess, and was particularly so during the Soviet era, is that collective thinking and group strategy are built into their approach to the game. Given that chess is a game in which each player unlocks myriad possibilities, it stands to reason that playing with the support of a group of advisors, each with his own unique perspective, beats going it alone.

We like lone heroes in the West, particularly in the United States, and we love tales of history-changing geniuses. Admittedly, the riveting biography of an entrepreneur who succeeded against all odds (Steve Jobs comes to mind) is bound to be more entertaining than an even-handed account of several people who had a fruitful professional partnership that lasted decades. But our stories of rugged individuals too often leave out the best part: the diversity and vast potential of a brain trust. My own profession, architecture, is well known for its constellation of “starchitects.” Since the era of Frank Lloyd Wright, design professionals and the general public alike have been fascinated by stories of path-breaking architects and builders who made an indelible mark on the world with a soaring skyline silhouette or an iconic landmark that everyone recognizes. But it probably goes without saying that no one builds a skyscraper—or a rural development or a new museum building—alone. Far from it. Every architect who makes a contribution to the built world does so with a team. It’s time we shine a spotlight on this dynamic and all it can accomplish. This means learning to see success as mutually beneficial rather than zero-sum.

The organizational psychologist and Wharton Business School professor Adam Grant explains that the “win” pie, as he calls it, isn’t finite. Quite the contrary, it expands with the number of innovative thinkers who seek its rewards. In a 2019 New York Times op-ed, Grant makes the case for a business strategy that initially sounds counterintuitive: reach out to your biggest professional rival when you need help. This sounds strange on its face; why work with the person or team whose goal is to beat you at your own game? But Grant provides striking real-world examples of this approach that have yielded stellar results, from the world of sports—where athletes tend to perform better when their closest rivals are competing in the same event—to the case of aviation entrepreneur Wade Eyerly, who found a lifeline for his startup, SurfAir, from the team at his chief competitor, another new airline company called JetSuite. The team at JetSuite, Grant explains, wanted to help Eyerly because they understood that SurfAir’s success was ultimately good for their own business, too. As SurfAir thrived, its success would bolster the larger marketplace for the kind of afford-able air travel they both offer, to JetSuite’s ultimate benefit.

In the tech world, innovation is already democratized, and the pairing of open-source code with affordable and easily accessible components means that a brilliant individual can make astonishing strides alone, working in the proverbial Silicon Valley garage. But not so in the world of real estate. Bringing a project to life, from initial drawings to finish carpentry, requires access to capital, connecting with good partners, and sourcing the right materials. Relationships and knowledge make these things happen. It’s not easy, but it’s also not impossible. While the tech world is new and nimble, real estate is arguably as old as civilization itself. It’s generational, storied, and, too often, closed to outsiders. Some architects and developers, like San Diego-based Jonathan Segal, are making strides in this arena already. Segal offers a series of courses called Architect As Developer, which are available online. One of his key points is the importance of relationships: lenders, builders, suppliers, makers. Cultivating and managing these can empower an architect to essentially become his or her own client, and stop relying on others to take the first step in a significant, career-changing project.

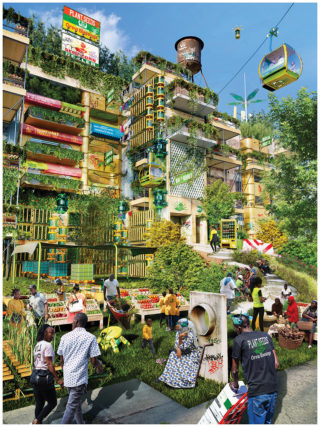

Democratization in real estate and design is the work of a generation. In order to expand the field and address the challenges of the future, we need to expand our definition of teamwork to include information sharing, inclusivity and even proposing collaboration with a competitor. In every aspect of development, from funding to building and marketing, the most successful projects will be built by a great team that represents a diversity of voices and ideas. Considering how these relationships are forged and finding ways to extend the tent will help more creative and inspired people realize that they, too, can become part of the team. The results are guaranteed to be better.

Drew Lang, AIA, is the principal of Lang Architecture and the founder of Brick & Wonder, a membership community that connects and supports professional leaders in real estate, design, and the built environment. Originally from New Orleans, Drew received a Master of Architecture degree at Yale University, and he currently lives in New York City