A pair of carbon-neutral micro homes, quietly nestled beneath an outgrowth of trees at the edge of a clearing in the backwoods of Taghkanic, NY, in the upper Hudson Valley, are unassuming beacons of a climate-positive future. “Home” is a loose classification; the residential structures—technically farmworker dwellings, per zoning laws—belong to Wally Farms, a 1,000-acre experimental farming and climate research incubator located 100 miles north of New York City. They are used year-round as guest accommodation and workshop spaces for researchers, educators, and the environmentally conscious to explore agricultural practices rooted in climate resiliency.

The homes themselves reflect the farm’s ethos of sustainability and discovery. Designed by architect and urban planner Kaja Kühl, founder of the urban design and research practice youarethecity, the micro homes achieve carbon neutrality primarily through the application of hempcrete, a relatively new building material. Hempcrete is a carbon negative biocomposite made from a mixture of lime and hemp hurds, the woody inner core of industrial hemp plants. This mixture can be used wet and sprayed directly, or it can be molded, dried, and cut into bricks for quick installation. Industrial hemp is fast growing, sequesters five to 10 times more carbon than trees, and utilizes what would otherwise be agricultural waste. Hempcrete is also mold resistant and nontoxic, making it safe to live and work with. Despite its many benefits, however, there are few precedents for hempcrete as a viable building material—at the time of the project’s construction, fewer than 20 buildings in the American Northeast were built with the substance.

“Th ere was an interest in taking the risk and learning about hempcrete,” says Kühl of the initial planning stages. The founders of Wally Farms—serial entrepreneur Susan Danziger and her husband, venture capitalist Albert Wegner—sought to commission two small, energy-efficient structures for the property, and “saw this as an opportunity to experiment,” says Kühl. They built on a relationship they had with Kühl in her capacity as a research scholar at Columbia University, where she led the school’s Hudson Valley Initiative from 2018 to 2020. During this period, Kühl worked with students from Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation to help develop an initial vision for Wally Farms, which contributed to the program’s overall research on the region’s spatial, economic, and environmental opportunities.

After exploring a number of biogenic possibilities for the project, including straw, cork, wood fiber, and cellulose, Kühl landed on hempcrete as the insulation material for both micro homes. It’s important to note that hempcrete is not weight-bearing; despite what its name suggests, it is not an alternative to concrete. Kühl instead prefers the more straightforward and accurate term “hemplime.” She explains, “We have to get away from that concrete comparison; I think it’s really hurting the understanding of the material.” The micro homes are supported by a wood-frame structure made of timber from a local lumber yard. A layer of wood fiber boards—a material with negative embodied carbon that the team sourced from Europe—envelops the layer of hemplime, reinforcing the structures’ insulating properties to meet operational energy targets.

Kühl and architect of record Roger Cardinal consulted with the Massachusetts-based construction company HempStone, which assembled a team of fabricators and installers that specialize in the application of hempcrete. The team members installed prefabricated hempcrete bricks for the inner layer of the wall, which they then sprayed with a seven-inch layer of hemp-lime. Because the prefabricated bricks were already pre-dried, only six weeks of drying time were needed for the spray-applied mixture. “There were lots of other moments when something was missing and we were waiting for material, so over the course of the entire construction, those six to eight weeks we were told we had to wait didn’t seem significant,” says Kühl.

The hemp hurds, as well as the lime binder, were imported directly from a cooperative in France. While this might seem antithetical to achieving carbon neutrality, the amount of carbon sequestered, and the total sum of carbon emitted during the en-tire process, resulted in a net zero outcome. “I wanted to demystify this idea that only local can be sustainable,” explains Kühl, who wrote extensively on the tension between local and sustainable in a multipart project diary on Medium.com. “Of course, it would be great for many reasons if we could harvest hemp locally as a building material. Many in this field are working towards it. But it’s important to understand that most of our sustainable materials—be it insulation, high-performance windows, or even the tape that most passive house designers and installers use—currently come from Europe. That has some transportation emissions but, being close to the New York port, they’re lower than if we had shipped something from the Midwest.”

Hemp farming, with restrictions, became legalized in the U.S. in 2018, and hempcrete was only just approved as a residential building material in 2022. The lack of a readily available supply chain means costs for hempcrete are 30% to 40% more than for conventional insulation material. However, the shorter installation time for hempcrete partially off sets the overall cost for the project. Another benefit of hempcrete is its thermal properties; not only does the material provide high-quality insulation, it also creates thermal mass, which keeps the structures cooler or warmer for longer periods of time.

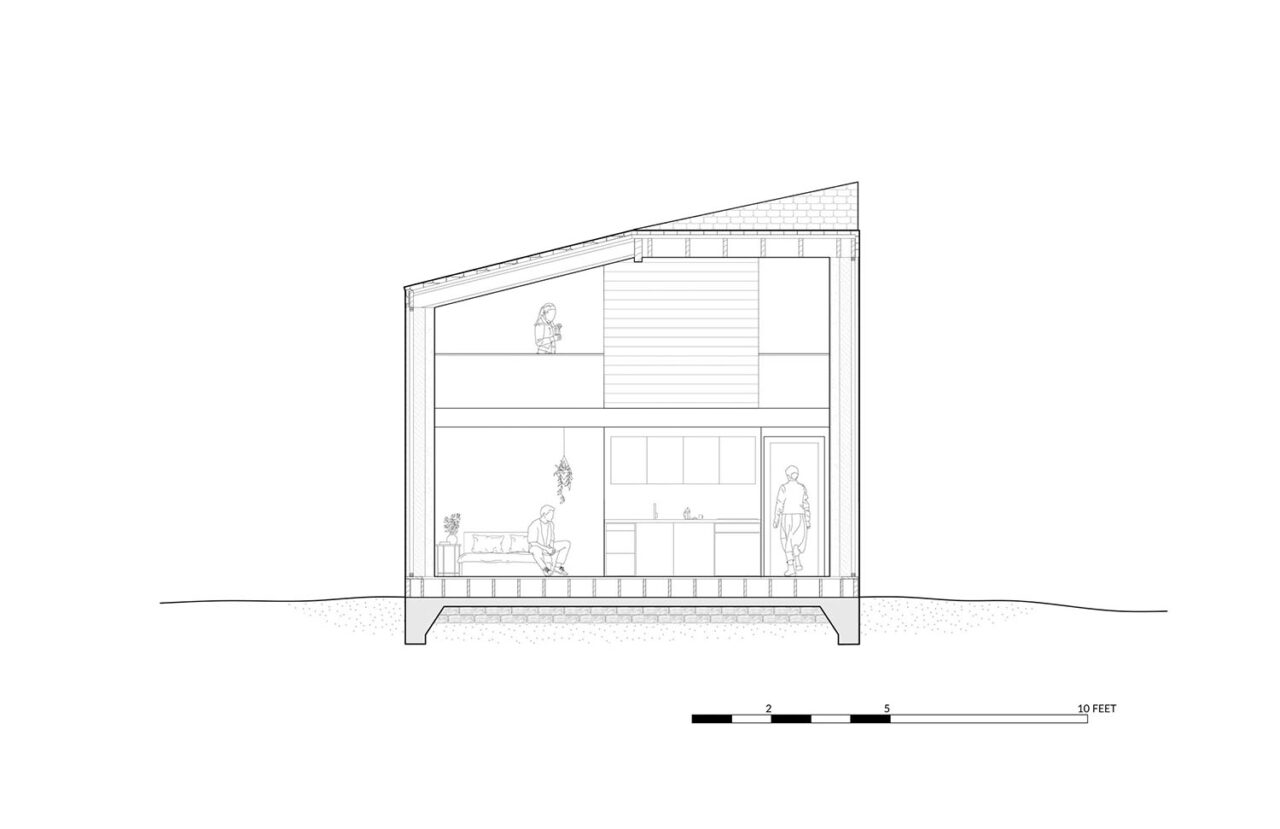

In addition to utilizing hempcrete, the micro homes at Wally Farms achieve carbon neutrality thanks to a small footprint, the use of other organic and locally sourced materials, and passive house techniques. Both structures are less than 400 square feet and connect to a solar microgrid that powers the entire property. The homes are strategically placed under shade trees to help with cooling in the warmer months; their windows face south and west, allowing sunlight to pour through and provide passive heat during freezing New York winters.

While the project provided an exciting opportunity for Kühl to experiment with a new biogenic material, her focus extends far beyond hempcrete itself. “I don’t have anything on the drawing boards right now where I’m using hemp again,” she says. “The idea is to be the material omnivore for natural materials. I don’t see myself becoming a missionary for hemplime alone.”

CORNELIA SMITH (“Street Level”) is a writer, design researcher, and occasional performance artist based in Brooklyn, New York. She has a master’s degree in design writing, research and criticism from the School of Visual Arts, where she devised a thesis project about the design of the pelvic exam.