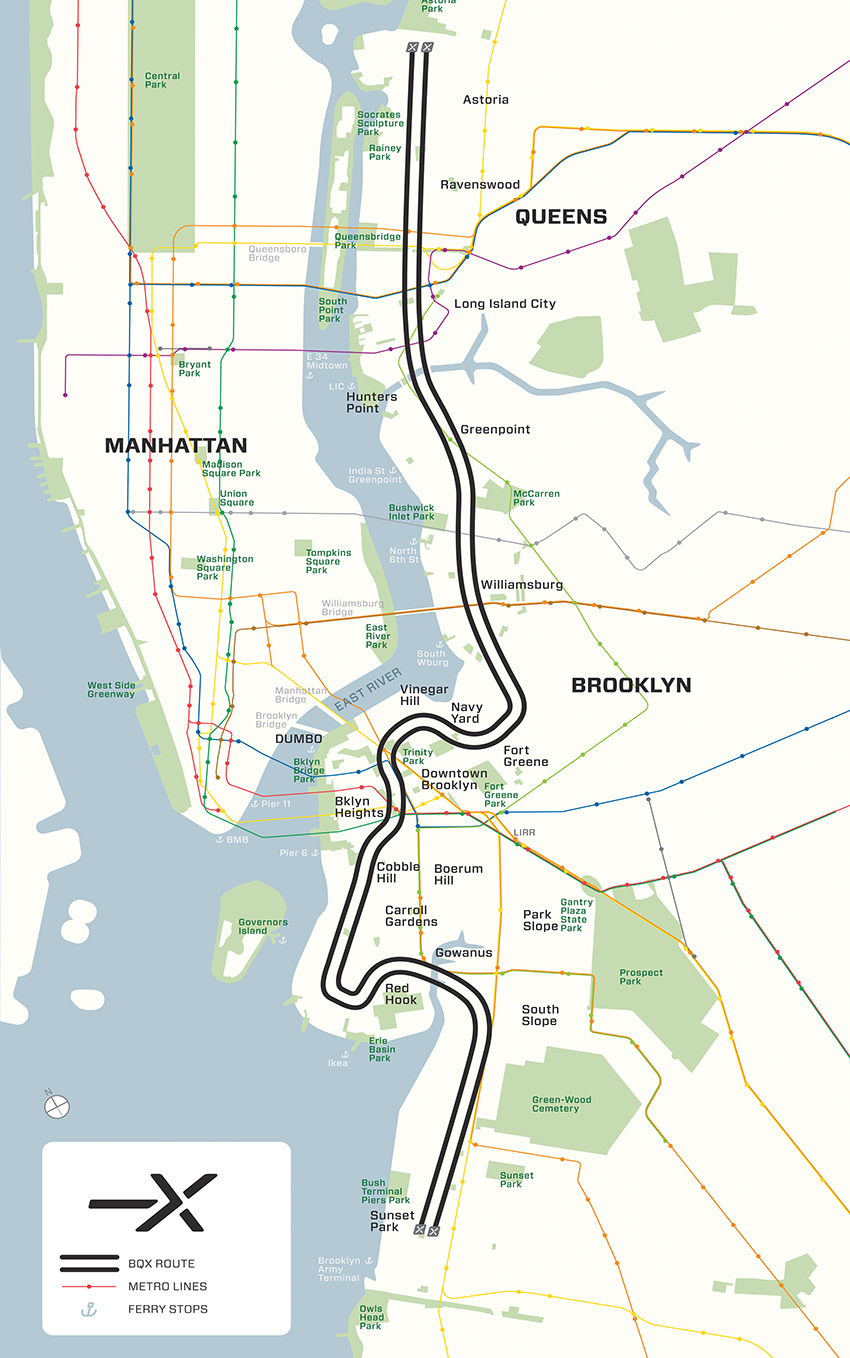

New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman wrote a piece in 2014 about the idea of a waterfront street-car running between North and South Brooklyn, which he credited to urban planner Alexander Garvin. The article elicited genuine excitement among transit enthusiasts and urbanists, as well as real estate developers.

Jed Walentas of Two Trees, a Brooklyn-based real estate development firm, backed a feasibility study that engaged experts like transit consultant Sam Schwartz. With Two Trees’s public relations firm BerlinRosen on the job of developing messaging and political support, the project that came to be known as “BQX” and Walentas formed Friends of BQX, an advocacy organization. After the early buzz of a High Line-like success story for transit, a leaked memo eviscerated the notion that it would pay for itself: the price tag had ballooned to the point where up to $1 billion in federal funding would be necessary. Discussions on the BQX went dormant.

The idea was revived in early 2020, however, by the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC), which had taken over the transit project’s planning and development. NYCEDC announced that BQX would soon begin the city’s approval process, launched a new website with a modified route, and hosted a series of public hearings. But COVID-19 was silently spreading through the New York City population and, in May, Mayor Bill de Blasio was forced to admit that BQX was again on hold. At a press briefing in September, de Blasio said that the BQX would have to be taken up by the next mayoral administration.

The most recent delay could be the project’s best hope, however. Since BQX was first announced, a new streetcar design has emerged—more flexible, significantly cheaper, high-tech, and carbon neutral—that is ideally suited to the BQX route. It could usher in the future of urban transit in a post-COVID world and, in the words of Sam Schwartz, “be a major game-changer.” Even the most ardent critics of BQX, who have characterized the project as a developer initiative, say this new streetcar approach, called Trackless Tram, is the future of public transit.

One convert is Gita Nandan, an architect who lives in Red Hook and is the co-founder of Thread Collective, a sustainability-focused architecture, design, and landscape firm. “To me, the beauty is its pure flexibility,” she said. “If there is a disaster event, you can change the route on the spot, or change it more permanently as needed. I know it requires placing these markers in the road, but that is nothing like what it takes to put rail in the roadbed. It works with what our disaster-prone future is going to look like—we need less hard infrastructure and greater flexibility.”

EVALUATING TRACKLESS TRAM’S POTENTIAL

Developed by the high-speed rail authority in China as a next-generation light rail alternative, Trackless Tram is currently operating in several cities there. Rather than running on rails, the streetcars have rubber tires that follow lines painted on the street using laser technology and GPS positioning—with centimeter accuracy.

“In light of the pandemic,” said Nandan, “who are we building this tram for? The wealthy? Or the people who need transportation in a crisis? We need lighter, faster solutions, and to me this is a great one. The tram is how we should be using Autonomous Vehicle (AV) technology in a dense urban environment. That’s why I’m excited about it.”

John Shapiro is a professor of planning at Pratt Institute and a long-time consultant on large-scale urban planning and design projects. He has been an outspoken critic of BQX for a number of reasons, including the cost, the timeline, the disconnect between transit and land-use planning, and the conversion of waterfront industrial land to luxury residential neighborhoods. “It’s not a transit project—it’s a real estate development tool,” Shapiro had said in an initial interview about the traditional light rail approach for the BQX. “It’s a 100-year investment, when much of the route—and virtually all of Red Hook—will experience regular tidal flooding in 30 to 40 years. It’s doubling down on waterfront development. I don’t see it as good public policy.”

Shapiro had a very different take on a BQX that uses Trackless Tram, however. “It seems to be a winner on every count,” he said in a follow-up interview. “I have not studied it in-depth, so for all I know there’s 14 fatal flaws. But, as a point of departure, it would seem this should be seriously considered as an alternative. It offers transit to support the existing residential development without the significant disadvantages of fixed rail—the cost and long timeline. There are so many clear benefits for the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and for people in public housing who don’t have transit options. If it can run through the Battery Tunnel to Lower Manhattan, it would be a game-changer. And, in 25 years, if the route needs to be adjusted for tidal flooding, this can be done with minimal disruption.”

A MULTIPRONGED STRATEGY FOR NY TRANSIT

Sam Schwartz, who worked on early feasibility studies for BQX and remains a strong proponent of the project, offered his own analysis off Trackless Tram. “I’m one of those skeptics about AVs—they are not ready for the big stage of cities,” he said. “This uses AV technology, but there would be an operator who is accelerating and decelerating, and making sure passengers are clear of the door. With AVs, the plan is to get rid of all operators, or they are just sitting there doing nothing. One of the hardest things to do is sit there doing nothing, but always be ready for an emergency. With an operator, they’re always engaged. So this could be absolutely terrific.”

Outside of China, planning is underway to adopt this new transit design in Qatar in preparation for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, and in western Sydney after the Australian city experienced enormous expense and disruption installing traditional light rail in its downtown core. But the place that is furthest along with Trackless Tram is Perth—largely due to the advocacy of Peter Newman, a professor of sustainability at Curtin University, who was awarded the Order of Australia for sustainable transport and urban design in 2014. Upon returning from a visit to the factory in Zhuzhou, China, where Trackless Tram continues to be developed and improved, Newman co-authored a study and a series of articles and papers. In a paper he co-wrote for the Journal of Transportation Technologies in 2019, he quantified the significant cost savings of Trackless Tram compared to light rail. In Sydney, for example, laying 20 kilometers of track through the oldest part of the city took five years and cost about $130 million per kilometer. By contrast, Trackless Tram can be installed for as little as $10 million per kilometer. As a traditional light rail project, the BQX plan is currently expected to cost almost $3 billion; implemented as Trackless Tram, the project has a low-ball estimate of $170 million.

And then there’s the time frame. Trackless Tram is sold as a kit of parts. The three-car set (which can be expanded to five cars) comes with a station that can be assembled in a weekend, according to Newman. This might be an overly rosy scenario, but the speed at which it could be put in place is essentially as fast as the permitting process would allow.

Cheaper isn’t just about saving money, however—it’s about reducing the pressure on real estate to pay for a very costly transit system. In other words, Trackless Tram has the potential to reinforce the development of affordable and attainable housing.

David Erdman, chair of Pratt Institute’s graduate architecture and urban design programs, and an informal advisor to Friends of BQX, was the only New Yorker interviewed for this article who had previous knowledge of Trackless Tram technology. Having lived and worked in Hong Kong and Taipei, he’s attuned to developments in Asia. “We have this 20th-century idea that one big system fixes every-thing,” said Erdman, “but we can’t sink all our resources into a single project anymore. We need projects like this that can work with both legacy transit and new innovations like scooters and e-bikes. What if this became part of the plan for fixing the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway? That’s how we need to be thinking in the 21st century.”

With the pandemic continuing to change the way New Yorkers live and commute, and exposing the need to serve the city’s neighborhoods more equitably, 21st-century thinking may finally start to catch up with technological possibilities.