When Ryan Cassidy began working on his first Passive House project in 2014, he was fascinated with the engineering and potential to save power. As director of sustain-ability and construction at RiseBoro, a New York-based community partnership, he was impressed by how the fastidiously insulated and energy-efficient building standard radically decreased heating and cooling costs. But since RiseBoro finished that project, Knickerbocker Commons in Bushwick, Brooklyn, which has 24 units of affordable housing and uses only 10% of the energy of a traditional apartment building, Cassidy has realized that energy savings is just the start. “When you build better, there are cascading benefits beyond using less energy,” he says.

It’s said that everything begins at home. For an entire wish list of progressive goals, including environmental progress, better health outcomes, and cheaper living for disadvantaged communities, it’s hard to beat the wide-ranging impact of sustainable, affordable housing. In a nation that has long suffered from an affordable housing shortage and environmental injustice, this change should be welcome, especially in New York. The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA)—which operates 400,000 public housing units in the city—has recently been dogged by stories of mold, heating malfunctions, and lead paint. Last fall, Data for Progress proposed a $48 billion plan for a Green New Deal that would retrofit NYCHA’s buildings; upgrades would eliminate emissions by 2030, provide 11,000 jobs, cut asthma cases by up to 30%, and decrease utility costs by $200 million a year.

Even small investments in improved buildings have concrete impacts on the health and financial outcomes of low-income communities. A 2015 study of energy-efficient housing in Virginia found the investment saved residents an average of $54 a month per unit. Another study the same year by the Oakridge National Laboratory discovered that simple weatherization provided benefits beyond lower utility bills; adult residents avoided hospitalizations and missed fewer days at work, and kids suffered fewer incidences of asthma.

“We feel like we’ve been shouting this from the rooftops for a few years,” says Elizabeth Beardsley, senior policy counsel for the U.S. Green Building Council. Across the nation, and in New York City in particular, communities are paying more attention to establishing better building and energy codes, adding green space, and improving equity. “The confluence of the pandemic and equity issues this year have showcased the disparate impacts of where we live in a new way,” she says.

In the last decade, New York City has seen growing momentum for more sustainable, affordable housing. Passive House construction has become a recognizable and cost-effective standard for apartments, now just a few percentage points more expensive, at most, than standard construction. New community solar energy projects and battery storage pilots have increased renewable power generation. Building electrification, which swaps out inefficient, fossil fuel-powered heating systems and appliances, improves indoor air quality and minimizes health issues such as childhood asthma. “For too long, the environmental justice movement has been on the sidelines,” says Krista Egger, vice president of national initiatives at Enterprise Community Partners, a non-profit focused on affordable housing development. “Now, with the impending nature of climate change and cities like New York instituting a variety of climate plans and targets, it’s in the spotlight.”

GO PASSIVE TO BE AGGRESSIVE AGAINST CLIMATE CHANGE

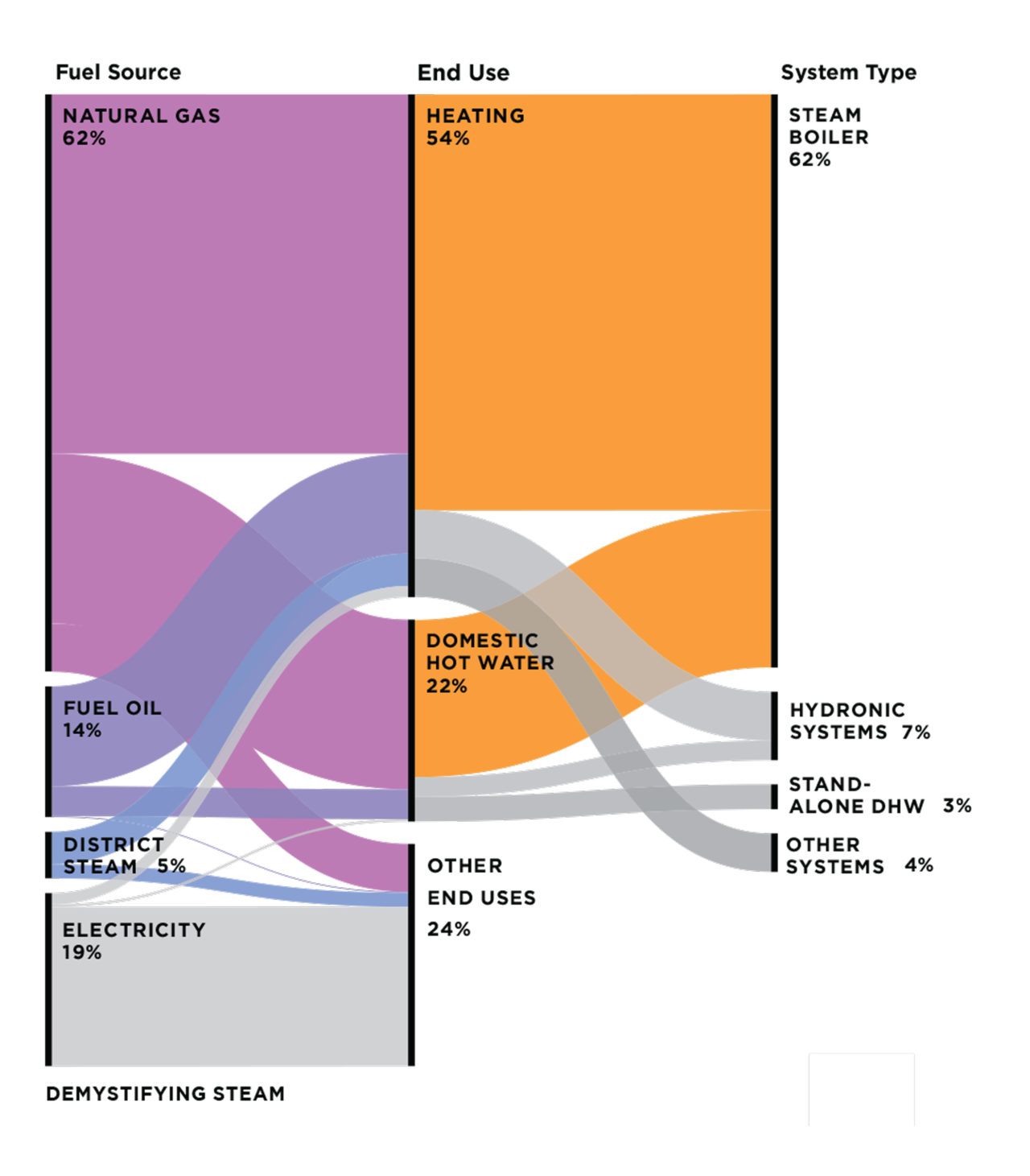

Whether it’s their environmental impact or the impression they make on the health of their residents, buildings have enormous footprints. For many reasons, measuring and reducing those footprints both start with addressing heat, especially in New York City. Since so many buildings still rely on steam heat, a relic of turn-of-the-century design found in 80% of residential buildings, the city collectively wastes extensive energy on heating.

Roughly 70% of climate emissions come from buildings, with most of those emissions, 40%, using fossil fuel heat to warm large, multifamily buildings, according to John Mandyck, CEO of New York’s Urban Green Council. Moving buildings off this kind of heating system requires a complicated switch, including the installation of electric heat pumps and a huge expansion of renewable power, two massive infrastructure and capital investment challenges. But making such a change does more than slash emissions and costs; boilers in basements—especially aging ones in older buildings, including the 25% of NYCHA buildings constructed before 1960—typically burn oil or natural gas, releasing carbon dioxide and other air pollutants that exacerbate respiratory health issues.

The affordable housing sector has traditionally focused on building as many units as cheaply as possible, says Egger—the right strategy if your focus is housing as many people as possible. At the same time, sustainability campaigns hadn’t focused on residential construction. But the lower costs of green building technology give both campaigns a winning issue; the savings from residential energy efficiency means you can build more without sacrificing quality, all while locking in lower operational costs. “This is a smart money move,” she says. “We tell developers reluctant to go green that the utility costs in a building you operate is one of your only controllable expenses. You can’t control property taxes.”

RiseBoro’s Cassidy says he’s found a Passive House project can cut utility costs by 60% to 80%, which filters down directly to residents. Justin Stein, senior vice president at BronxPro, another green affordable housing developer that builds to Passive House standards, says that by underwriting the utility savings, his new projects leverage a larger loan to pay for the more expensive insulation and ventilation systems. On a large scale, this means buildings would require fewer subsidies from the government, resulting in more units.

The added quality-of-life benefits don’t hurt, either. By regulating air temperature, the building controls moisture, meaning no drastic temperature shifts and no mold. Heavier insulation results in quieter units. And since each apartment is sealed to trap in heat, fewer pests travel between floors and there is no stack effect (where smells and smoke travel up air vents). “Whether you’re living in a NYCHA unit or a $5 million apartment, everyone in New York has dealt with loud sirens and cooking smells from your neighbor,” Cassidy says. “We think we have to put up with these things to live here, but they can all be mitigated by Passive House strategies.”

REWRITING THE RULE BOOK FOR RESIDENTIAL LIFE

Everyone should have quieter, healthier, and cleaner apartments. But getting there as a city is a generational challenge. Seeking to jump-start that process, state and local regulators and lawmakers have recently passed a suite of updated building standards and energy goals, including last year’s Green New Deal and Climate Mobilization Act, which seek to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from the built environment by 40%. The state’s building code has also gotten progressively more focused on energy efficiency, with an ambitious stretch code that just went into effect in New York City. Recent policy changes and initiatives by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), including investment in clean energy for low-income residents and financing for green multifamily construction, are all geared towards connecting the dots.

This push is mirrored at the national level, where a growing number of Democratic proposals focus on sustainable housing: Vice President Joe Biden’s plan would focus on making low-income housing more energy efficient; vice presidential nominee Senator Kamala Harris and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed a Climate Equity Act; and the People’s Housing Platform, offered by Ocasio-Cortez and the Squad, includes money for extensive clean-energy retrofits.

In the coming years, improving standards may be only part of the challenge. Budget shortfalls from the COVID-19 crisis may hamstring the ability of state and local leaders to fund new affordable projects. Mandyck suggests using carbon trading. Local Law 97, part of the Green New Deal, places stringent carbon caps on buildings starting in 2024. Indeed, it is the toughest stand ever applied by any city on the globe; older buildings, especially commercial spaces, will struggle to keep up and likely have to pay huge fines. Mandyck says those fines should fund greener construction and electrification.

To realize the full potential of electrification, the city and state would need to radically revamp the energy grid with utility-scale solar and wind power plants. While a community solar project or solar panels on the roof of a public housing project can add renewable capacity—new city law mandates building owners add solar panels when feasible to new construction—local projects can really shine by creating more resilient neighborhoods.

The Marcus Garvey Apartments, more than 625 units spread over nearly two dozen buildings in Brownsville, Brooklyn, received an energy-efficiency revamp between 2015 and 2017, which added solar panels and a large lithium-ion storage battery the size of a standard shipping container. According to Nick Lombardi, senior management of business development at Enel X, which oversees the renewable power system, the renovation isn’t enough to power the entire complex—it generates 1.1 megawatts, while the complex hits a peak usage of 1.5 megawatts in the summer and 3 in the winter. But it does cut down on energy costs, which are factored into rent.

Lombardi says the key benefits for residents are resiliency—the apartments and daycare center are safe in case of emergency—and the elimination of costly new electrical generation infrastructure. The Marcus Garvey battery storage facility was funded in part by a program that sought to build up power generation in Brooklyn and Queens without resorting to peaker plants: small, dirty, gas-powered generators that are terrible for air quality. It’s not a coincidence that many lower-income neighborhoods are close to where peaker plants are located or would be built; pairing this kind of green infrastructure with affordable housing means less pollution for the neighborhood

REDUCE, REUSE, AND RECYCLE OLD BUILDINGS

New buildings and new infrastructure are just part of the solution. According to Mandyck, 90% of the buildings that will be standing in New York by 2050 have already been built, and retrofits and renovations can be an extremely expensive proposition. This makes RiseBoro’s ongoing Casa Pasiva Project in Bushwick a potential game changer. The first project funded by NYSERDA’s Retrofit NY program, the renovation will add cladding, efficient appliances, and new mechanical equipment to achieve Passive House status and, ideally, establish best practices for other such retrofits once it’s finished next year. “As architects, we need to take this process into our own hands,” says Chris Benedict, RA, architect for Casa Pasiva and longtime collaborator with RiseBoro. “We can’t wait for a program to do it. We have to learn and do it now.”

From retrofitting millions of apartment units to developing new renewable power capacity, the city faces an unprecedented infrastructure challenge if it truly aims to meet its own ambitious climate goals. But the hope of advocates, architects, and developers is that current programs and incentives not only generate broader support for “better buildings” and healthier communities, but create evangelists with every new tenant. “When I give presentations to tenants in the different buildings I design,” says Benedict, “I tell them I hope they’re the ones telling the next group of people how great it is to live here.”