by: Matt Shoor AIA LEED AP

Courtesy formlessfinder

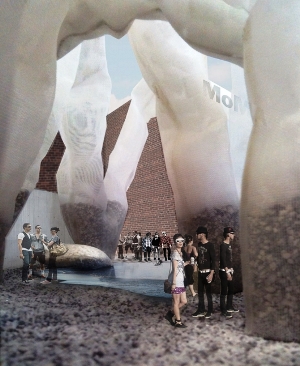

Two views of Bag Pile. More of formlessfinder’s work is on display at the Center for Architecture as a part of the “New Practices New York 2012” exhibit.

Courtesy formlessfinder

Event: Practice Makes Imperfect: formlessfinder

Location: Axor NYC, 06.28.12

Speakers: Garrett Ricciardi, Assoc. AIA, and Julian Rose, Assoc. AIA, formlessfinder; Philipp von Dalwig, Assoc. AIA, LEED AP, Co-Chair, New Practices Committee.

Organizers: AIANY New Practices Committee

Underwriters: Axor Hansgrohe; NRI

Patrons: Sure Iron Works; Thornton Tomasetti

Supporter: Samson Rope

Media Sponsor: The Architect’s Newspaper

In the world of contemporary architecture, form is everything. As human culture has slowly prioritized the visual, the realm of the built environment has followed suit. Ideas about design and construction now are transmitted primarily through images. As a result, in an attempt to present evidence of uniqueness or superiority, architects are designing for the camera. Form, which was once dependent upon the unique structural properties of a material, now is manipulated and distorted by designers beyond the capacities of conventional structural systems.

In such a building culture, it takes audacious and adventurous architects to refute the supremacy of form. Garrett Ricciardi, Assoc. AIA, and Julian Rose, Assoc. AIA, of formlessfinder, one of the winners of the 2012 New Practices New York Competition, are such designers. Like explorers of old, these designers have sailed into the unknown by adopting lack of form as the raison d’être of their practice.

According to Rose and Ricciardi, their interest in the formless first emerged from failure. The architects under whom they apprenticed were frequently frustrated that designs could not be constructed as envisioned. Rose and Ricciardi wished to elude dissatisfaction by preventing form from entering into the design equation. Instead, architecture would be generated by imposing a limited number of rules on a set of messy circumstances or materials. Since the designers had no preconceived notions of specific form, the resultant “design” could be accepted wholesale without disappointment.

One of the most engaging and successful examples of formlessfinder’s theories put into practice is its competition entry for the 2011 MoMA/P.S.1 summer pavilion. Entitled Bag Pile, the design was composed of a series of geotextile bags – filled with gravel, foam, and other loose material – arrayed around the courtyard in a non-linear fashion. The bags created arches, stretched skyward up to 40 feet in height, or lay languidly on the ground. Thus, the arrangement of elements created random interstitial space in the gaps between objects.

Rose and Ricciardi admitted that, given the preeminence of the photograph or rendering as a means to express a design, they are still unresolved as how to best represent their ideas. The formless is not accustomed to posing well for the camera. Regardless, in an era when architectural form has become increasingly more elaborate and ostentatious, it is especially comforting to know that some young thinkers still question basic assumptions about the role of form in spatial design.

Matt Shoor, AIA, is an architect, writer, and educator currently employed by Macrae-Gibson Architects. He is a frequent contributor to e-Oculus, and recently received his architectural license. Matt can be reached at mshoor@gmail.com.