by: Paul Broches FAIA and Steven Goldberg FAIA

When Aldo passed away on 05.15.16, he left an unforgettable legacy. He was a great architect and teacher who moved through his life of remarkable achievement with a humility rare among his peers. It is heartwarming to know that he touched many people in our field. My partners and I have received many condolence notes that bear this out.

Many messages came from former students representing the arc of his professorial career teaching at Cornell, Penn, and Columbia. His devotion to teaching was not always evident, as we students were often left waiting for his arrival in the studio at Avery. Wondering where he could be, our outsized fantasies often left us laughing as there was no more dignified man than he. One could not be angry with him, because once in place he was focused on the task at hand and clearly loved the rapport with students. Without exception, they describe their experience with him as formative and life changing – whether it was for one crit or a semester’s worth.

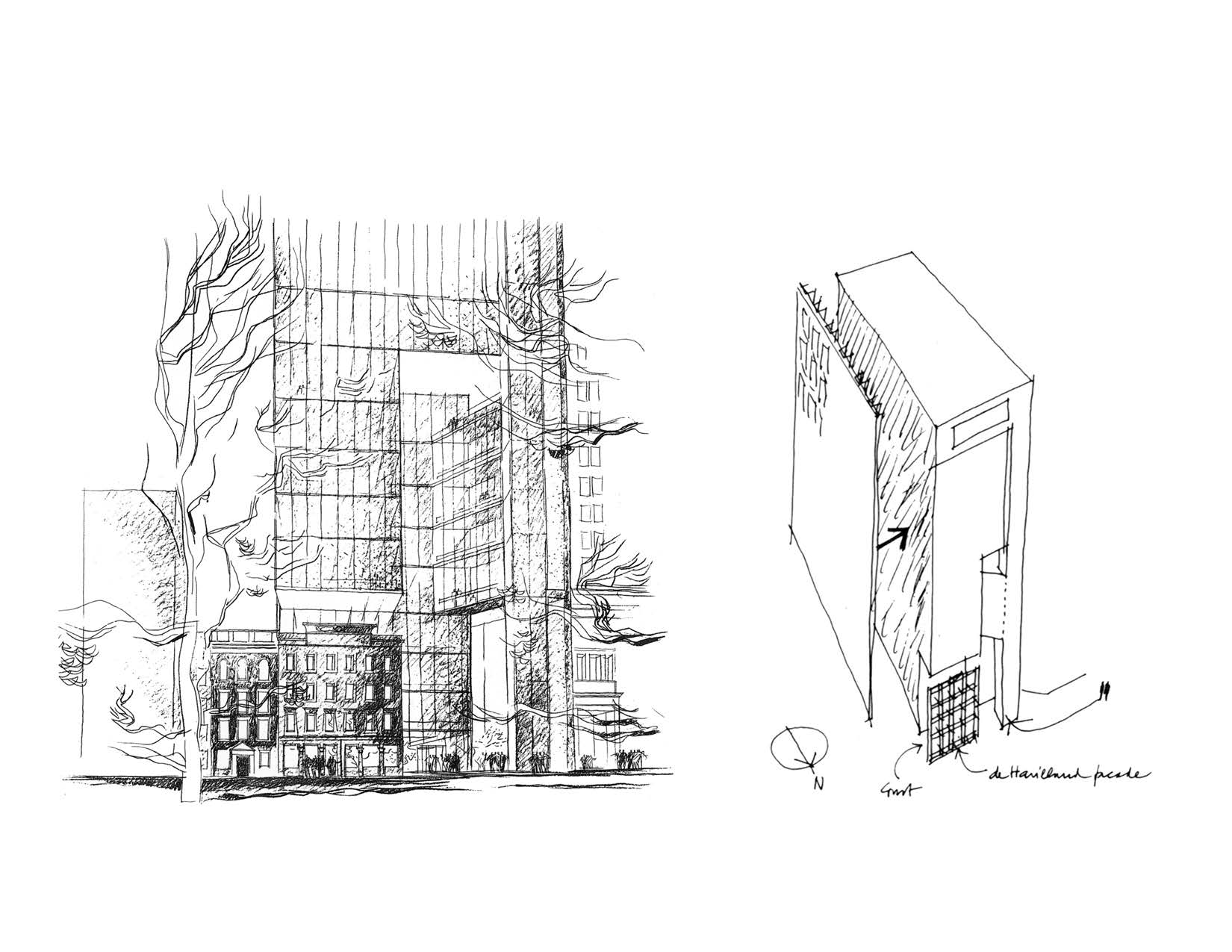

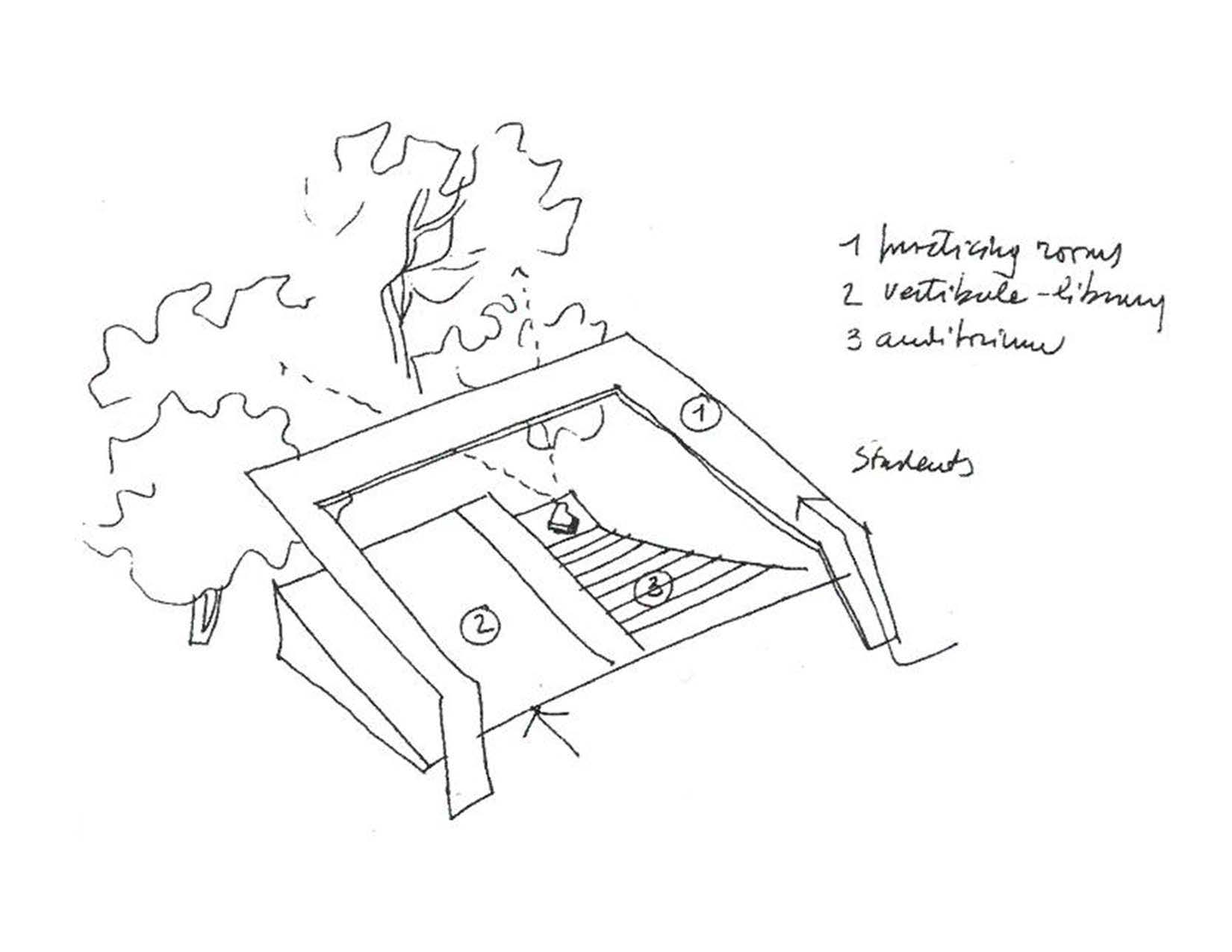

One of the emails received from a former student described a familiar scene: how Aldo approached his drawing table, pulled up a stool, and started sketching lightly on a clean corner of his drawing. A few tentative lines drawn, and then mutual smiles of recognition. With four or five lines Aldo diagrammed a seemingly muddled scheme, bringing clarity to the student’s intentions and the inherent possibilities that lay ahead. From there the conversation flowed easily, as teacher and student were on equal footing.

These enriching experiences of revelation and generosity played out in similar fashion in the office. Those of us who were his students found the office dynamic uncannily similar. Work sessions were collegial. In our office above a grocery store on 97th Street we would sit at a large blue square table where ephemeral sketches rolled out onto yellow trace from Aldo’s ubiquitous #314 Berol pencils.

If we were fortunate, Aldo segued to sketch a Roman villa he had investigated, or gave a brief lecture on historic precedents that might inform our thinking about the project at hand.

Concepts emerged with the beautiful tremulous lines that were his trademark. Numerous lines were overlaid on one another as the team conversed. A team member might remind him that we had left out an important element of the concept. Aldo would add another layer to the sketch. This process would continue until the sketches became more certain. As the consummate teacher, Aldo might add, as he did in his writings:

“Architecture begins with a concept before aesthetic consideration.”

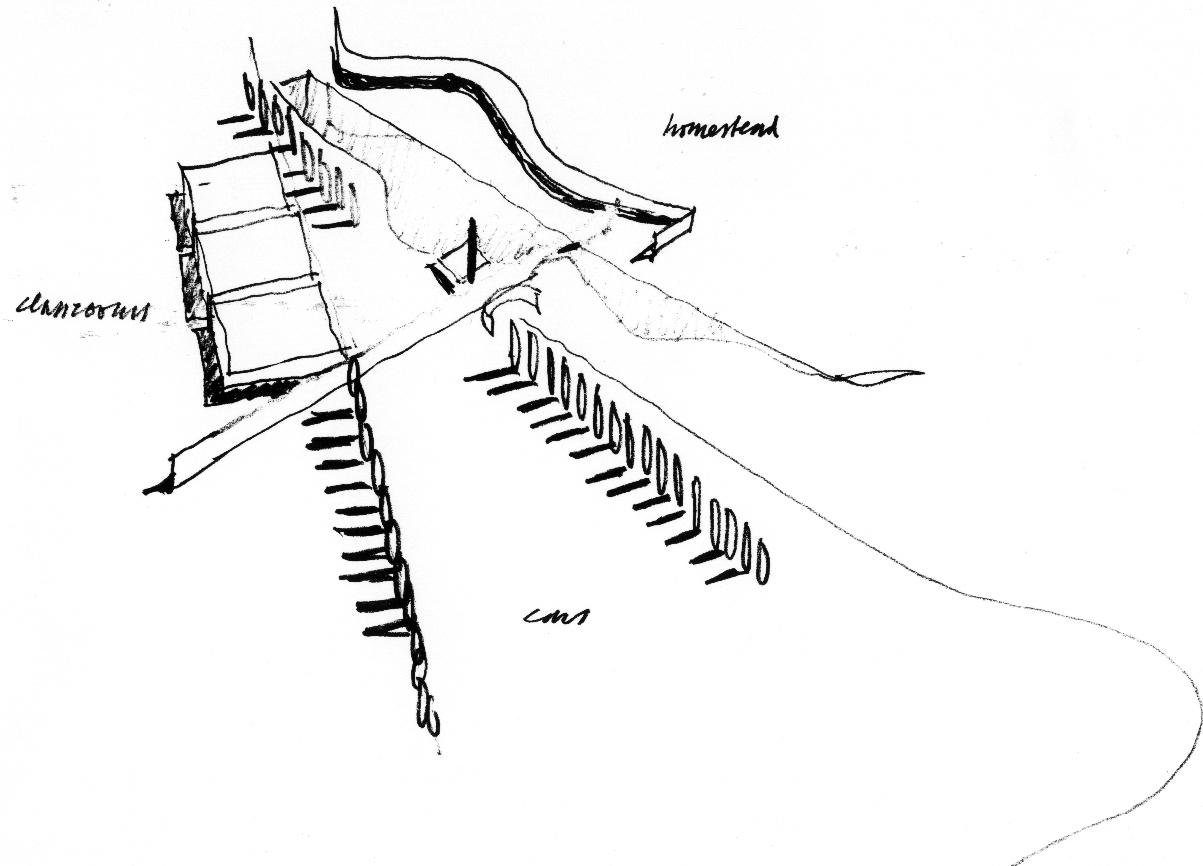

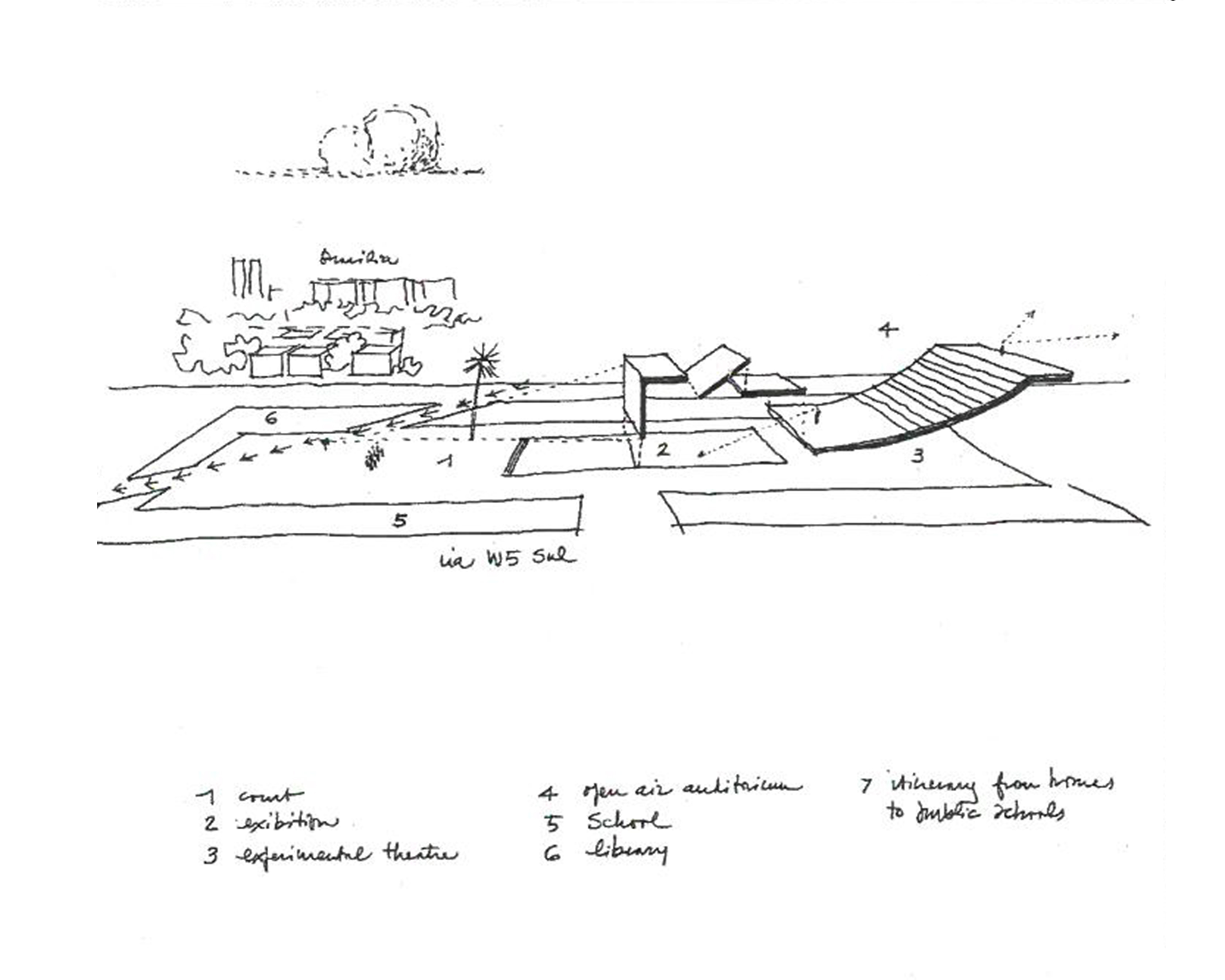

Concepts were often generated from describing a person’s itinerary through a site, or from a noteworthy line of trees that called for a response. Context was always critical and landscape provided many clues – the beginning of a site plan. A ground-hugging, gestural plan would be anchored to the site. Unusual land forms and compelling trees were amplified to their necessary importance. For the development of a site plan for the IBM Advanced Business Institute in Palisades, NY, for instance, a stream that coursed through the 100-acre site became the informant, and a pond that developed where the stream had been dammed up became the touchstone. For Aldo, this was the beginning of place. He looked beyond expected boundaries, adapting to topography, searching for a way to settle the structure gently in the landscape.

“In architecture, I like to see this realization of a sense of place: this has been and is the object of our work…a “good” place has to do with how well it promotes human accommodation.”

Aldo was a humanist in every sense of the word. The initial sketches with their provocative force lines had a depth to them that contained not only spatial concepts and functional requirements, but also connections to the surrounding context and spiritual aspirations. There were moments of silence when he was struggling to marry the two. As his sketching continued, notions about site gradually morphed into building form. The process was organic. The structure was usually geometric with some special gesture that merged the building and the landscape.

Aldo’s “management style” was brilliant. A good meeting was had when a stack of sketches had accumulated, each one laid on top of the others, reflecting Aldo’s search for direction and the contributions by the others at the table. By the end of the meeting we were hooked, and Aldo would know that we had come to a concept for which there was agreement. We had the freedom to build on the concept, all having witnessed the formulation of the parameters.

The work sessions with Aldo would wrap up with him asking us to test ideas against normative constraints. Sometimes we were skeptical, but early on I learned that his seemingly intuitive explorations were founded on profound intellectual rigor. In addition to client aspirations, history, philosophy, and art were always at his beck and call. The concepts that emerged from our collaborative sessions, strongly guided by his hand, were usually right on. The sessions often ended somewhat abruptly when Aldo would get a phone call and disappear from the table. I was never sure how the phone knew to ring at that very moment. The break gave each of us the time to absorb the discussion, prepare, and look forward to the next get-together. We knew that each time Aldo took pencil in hand, learning would continue. Those lessons serve me well every day.

Paul Broches, FAIA, Partner, Mitchell | Giurgola Architects

——————————————————–

There has been a great deal written about Aldo’s architectural accomplishments and I want to focus on his practice, which was unique among architects, passing through three worlds: Philadelphia, New York, and Canberra, Australia.

In Philadelphia he set up an office with Ehrman B. Mitchell in 1958 and taught at Penn. As a faculty member he was in a unique position to attract top students, and as most discovered, there was very little difference between working with him in the design studio or in his office: sitting at the drafting board individually or as a group, developing ideas through sketching on yellow trace. As a member of the Philadelphia School, he carried its philosophy of a more inclusive, culturally responsive, and humanistic architecture into the office, which informed all of his projects. Mitchell focused on the management of the practice and technical and detailing excellence of the work. In Philadelphia, Aldo’s career was taking off and he executed many significant commissions (Liberty Bell Pavilion, United Fund HQ, Penn Mutual), as well as winning or placing highly in design competitions (AIA HQ, Boston City Hall).

In 1965, he was appointed the first Chair for Architecture of Columbia University’s School of Architecture and moved to New York, setting up a small branch office with his Penn studio assistant, Robert Kliment, FAIA. The office grew rapidly, equaling the size of its Philadelphia counterpart. Again, through his teaching he was able to draw in key students, some of whom were later to become his partners (Steven Goldberg, FAIA, Paul Broches, FAIA, and Jan Keane, FAIA). In 1979, the firm won the competition to design the Australian Parliament and an office was set up in Canberra with Richard Thorp. Several key members of his Philadelphia and New York staff moved to Canberra and were joined by Australian architects to lead the effort. In 1986, the New York and Philadelphia offices amicably severed their relationship and Aldo withdrew from the Philadelphia practice, which continued as MGA Partners.

Also in 1986, prior to the completion of the Australian Parliament, Aldo withdrew from the New York practice but agreed to its maintaining the name Mitchell | Giurgola Architects. The Australian practice flourished, exercising commissions throughout Australia and Asia. In 2004, Aldo retired and the firm changed its name to Guida Mosley Brown.

All three firms continue his legacy, and on numerous occasions Aldo expressed his appreciation for the quality of work being done. So how is it possible that three firms have been able not only to survive, but thrive after the departure of their Gold Medalist?

I believe there are several reasons:

He chose the right people with whom to associate, who were talented and complimented his prodigious design gifts. He built a well-rounded practice that embodied the Vitruvian principles of “Firmness, Commodity, and Delight” – beautiful buildings that were affordable and stood the test of time. Aldo fostered an atmosphere of collegiality in the office and was inclusive in the design process. He gave his colleagues room to breathe and grow. He was not a self-promoter or prima-donna, but was always willing to share credit. Clients recognized that he was not a solo flyer, but part of a strong team. His incredible work ethic and quest for design resolution was what really mattered to him. The credit came as a result of this.

Lastly, Aldo did not have a signature style. Rather his and the firms’ work was always grounded in the program, site, cultural milieu, and human habitation. Each project looked different as a result of responding to its unique condition. Each client was given a building that was specifically tailored to them. This office culture and design philosophy laid a strong foundation upon which the three firms built their future successful practices.

Steven M. Goldberg, FAIA, Partner, Mitchell | Giurgola Architects