by: Alexander Luckmann

Gabrielle Brainard, AIA, is interested in both the technical and cultural aspects of architecture. A facade consultant at Heintges and Associates, she was previously a senior associate at SHoP Architects, where her projects included 111 West 57th Street and South Street Seaport’s Pier 17. She has long combined her professional practice with teaching, and is currently a Visiting Associate Professor at Pratt Institute, teaching technical graduate courses. She has been published in publications including SQM: The Quantified House (2015), ARCH+, and CLOG. She co-edited Perspecta 41: Grand Tour (2008). Here, she tells us why we need stronger technical teaching and how she has been making the AIA her own.

Q: Who or what inspired you to become an architect?

A: Actually, I started as an urban historian. When I was an undergraduate at Yale, I became fascinated by the city of New Haven. You can really read the city’s history in the urban landscape—from the 17th century town green, to 19th century factory blocks, to the scars of 20th century urban renewal. My thesis, which was about the history of a street of row houses, looked at architecture as a part of material culture that reflected, at a small scale, the larger political and economic forces that shaped the city. The work I do now as a façade consultant is very different in scale, but the same sensibility applies. Façade systems are embedded in a global supply chain driven by forces much larger than a single building project.

Q: While at the Yale School of Architecture, you were an editor at the journal Perspecta. How did the process of editing and writing contribute to your education as an architect?

A: The process was a really positive collaboration with my co-editors and our graphic designers. Group projects in school can be a dismal experience, even though collaboration is key to how architects actually work. Having an experience where everyone brought their own sensibility and skillset to the table, resulting in a whole that was greater than the sum of its parts, gave me a glimpse of what practice, in its best form, could be like.

Q: Since graduating, you have continued to combine academia and practice, and you are currently Visiting Associate Professor at Pratt Institute. How do your teaching and design practices inform each other?

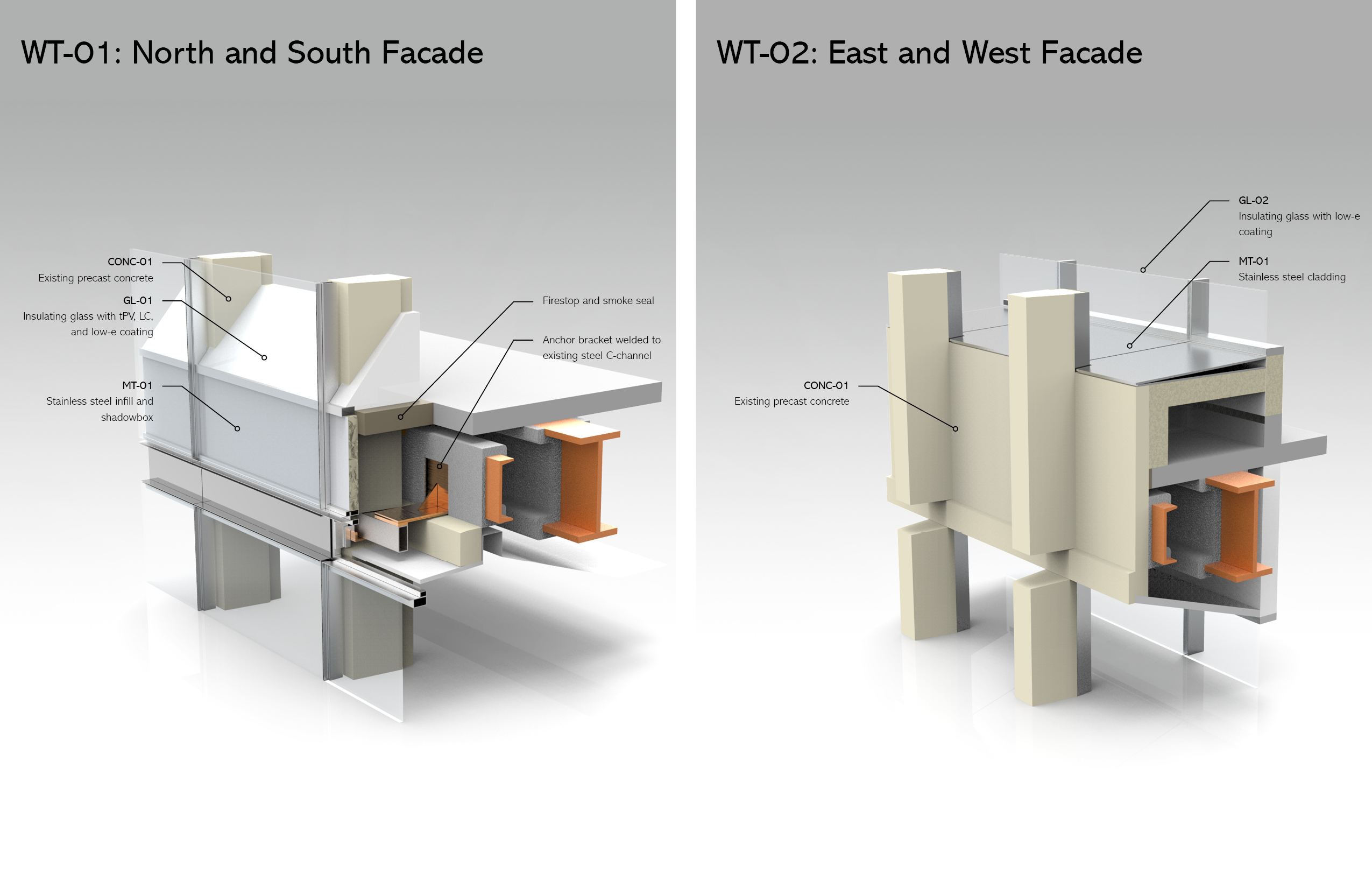

A: I teach technical courses to second-year graduate students at Pratt. We introduce architectural materials like steel, concrete and glass; discuss their origins and physical properties; and show how they are assembled into building systems. Then we spend a lot of time drawing details—specifically wall sections. The students consider the material implications of their design ideas, and learn to use technical drawings to test and refine their projects. That’s the official pedagogy of my courses. The unofficial pedagogy is to expose students to the technical culture of architecture, which is not well represented in American architecture schools. If we’re going to have better—meaning more integrated and elegant—buildings, we need a stronger technical culture, and the place to start building that culture is in schools.

Q: You are currently with Heintges & Associates, a Building Envelope & Curtain Wall consultancy. What attracted you about this mode of practice, as opposed to working in a full-service architecture firm?

A: It was a natural progression for me. I had been focusing on facades at my previous firm, SHoP Architects, for several years before making the move. The biggest difference I’ve noticed between the two modes of practice is time. In a full-service firm, you’re often looking for the quickest solution to a problem. As a consultant, you have the time to investigate the issue from many different angles and decide on the best course of action. In fact, you have to take the time to consider your response, because there is no other expert you can delegate to—you are the expert!

Q: Are you currently pursuing any research projects?

A: Yes! With two colleagues, I received funding from Pratt to install a wireless sensor network in Higgins Hall, the home of the architecture school. We’ll be measuring temperature and relative humidity in the classroom and studio spaces using Pointelist sensor kits developed by KT Innovations, the product development arm of Kieran Timberlake Architects. The idea is to make building science concepts real for the students by collecting data on the spaces they use every day (and sometimes all night, too). While the first step will be data collection, we’re planning to integrate data analysis and visualization into the curriculum as the project develops.

Q: You recently sat on the AIANY Nominating Committee and are involved with the AIA in numerous ways. Can you talk about your engagement with the AIA?

A: I’ve been an AIA member for several years, but I never considered getting involved in the chapter until after the election. At that point, many of my friends and colleagues were questioning whether the organization represented their values and priorities—a feeling summed up by the hashtag #NotMyAIA. I felt that, rather than stepping back from the organization, maybe I could make it “My AIA”—meaning, for me, reflective of architects’ diverse identities and modes of practice—by getting involved. Through my work on the Nominating Committee, I realized that we are lucky to have a vibrant chapter in New York that does not shy away from taking a stand. There are many ways to participate and relatively low barriers to entry. The first step is just showing up. The second step is bringing your friends, so I’ll be working on that next.