by: Bill Millard

New York has more supportive housing than any other American city, but no one pretends the available stock of these residences – affordable housing with on-site supportive services – is adequate to the need. Mayor Bill de Blasio’s effort to expand the city’s affordable housing puts a special spotlight on this sector. Thoughtful design makes the difference between dreary institutional stereotypes and dignified, even desirable, residences, noted panelists assessing the history and prospects of New York’s supportive-housing endeavors. Serving both as a snapshot of current municipal policy and a profile of innovative projects by specialist Jonathan Kirschenfeld, AIA, and by the award-winning organization Common Ground, the event offered pointers for architects working in this area, and broader observations about the powerful changes that purposefully crafted buildings can make in people’s lives. Witty, enthusiastic, and practical comments by a current resident capped off the presentations, providing a firsthand perspective that too many professional gatherings take for granted.

The single-room-occupancy (SRO) building was a viable typology for decades, Kirschenfeld and others pointed out, before a combination of factors led to a drastic gap between supply and demand. Moderator Nicole Branca, deputy executive director of Supportive Housing Network of New York, traced the increasing need for supportive housing to the psychiatric deinstitutionalization movement of the 1970s and the consequent surge in homelessness through subsequent decades. This combined with a legal moratorium on new SRO construction imposed in 1954 and a 1955 measure offering tax abatements for conversion of SRO units into market-rate housing, hotels, or offices. Caught in a pincer movement between deinstitutionalization and disinvestment, the populations needing affordable rooms and supportive services flooded into the streets.

People of limited means, including newcomers to the city as well as challenged populations, could find a room at buildings like the Barbizon Hotel or a Salvation Army facility for $106 to $154 a week in the 1970s, Kirchenfeld noted. Units in those buildings are now far fewer and of course, after condo conversions and the depredations of the real estate market, unimaginably costlier. Philanthropic and faith-based organizations did what they could to provide housing for the mentally ill and other people at risk, including medically or psychiatrically challenged veterans, the HIV-positive, the formerly incarcerated, survivors of domestic violence, LGBTQ youth, youth aging out of foster care, and others. Common Ground, in particular, has a 25-year history marshaling professional and material resources to create special-needs housing that is not just adequate but exceptional (acting on the tendency recognized by Elissa Winzelberg, FAIA, that “architects are wired to care”). Still, the Supportive Housing Network of New York (representing 200 nonprofits statewide) is fighting an uphill battle. The NIMBYism that many neighborhoods show toward supportive facilities exacerbates the problem. To win community approval, facilities must innovate in several directions at once: functionality, aesthetics, sustainability, and security for both residents and neighbors.

Leaders in supportive-housing construction have developed a repertoire of design strategies that get the most out of clients’ tight budgets and challenging, often oddly configured, sites while presenting an attractive face to their neighbors. Block-and-plank construction can be remarkably cost-efficient, and variation in ceiling heights (even a modest rise from 8 feet in wet zones to 8 feet 8 inches in living rooms) creates attractive internal sequences. Courtyards (“outdoor living rooms”) are the heart of supportive buildings, offering a public space that can draw residents out of their private rooms and counteract the detrimental effects of isolation. Kirschenfeld noted that the zoning code’s Use Group 3 (commercial facilities) allows smaller courtyards, along with two other key differences from Use Group 2 (residential): no parking or density requirements. “There’s nothing very New Yorky about a 30-foot by 40-foot courtyard,” Kirschenfeld pointed out, arguing that the 1961 zoning specifications were inexplicably “dropped from above,” and should change to make it easier for more buildings to provide this type of amenity, making the efficiencies possible in Use Group 3 supportive housing extend to more buildings. The courtyard at the Domenech on St. Mark’s Avenue in Brooklyn, he noted, with a checkerboard pattern of Kalwall translucent curtain-wall panels, is a particular gem, “sympathetic with the clouds and sky.” Another powerful element is community libraries: returning to one project to find four octogenarians doing yoga in the library, he said, was “the most satisfying moment of my career.”

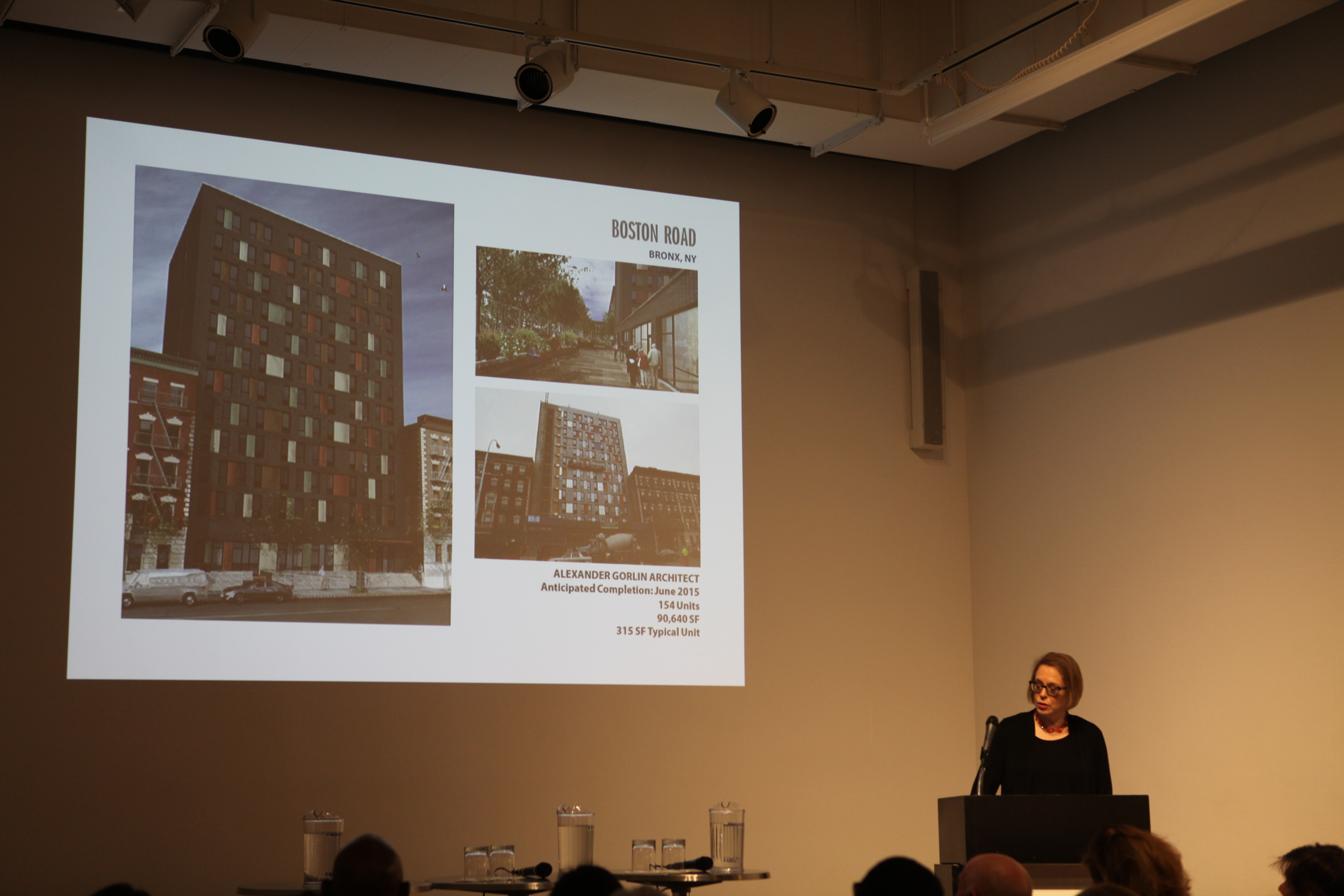

Kirschenfeld is not alone in bringing innovation and high efficiency to this typology. Common Ground, Winzelberg noted, has paired prominent architects with recent and forthcoming projects: Ennead Architects at Brooklyn’s Schermerhorn (2009); Kiss + Cathcart at the East Village’s Lee (2010); Alexander Gorlin at The Brook (2010) and Boston Road (2014) in the Bronx; COOKFOX at the Hegeman in Brownsville, Brooklyn (2012) and Webster Avenue in the Bronx (opening in May 2015); and FXFOWLE at the South Bronx’s La Central (scheduled to start in 2017). Providing between 160 and 315 units each, these buildings meet high performance standards (LEED Silver or above), and integrate landscaping along with customized features (e.g., a black-box theater in the Schermerhorn, which has many long-term tenants from the entertainment industry). Emily Lehman of the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) Supportive Housing Loan Program pointed out that her department increasingly supports new construction, taking an early hands-on approach to design (aided since 2012 by dedicated Design Guidelines for Supportive Housing). Beyond its longtime goal of 500 new units per year, bumped up to 1,000 per year in 2012, HPD, under Mayor de Blasio, is now committed to adding 1,200 per year over the next decade.

The U.S. is the world’s leading incarcerator, holding more than 0.7% of its population in prisons and jails, according to the International Centre for Prison Studies at King’s College London (about 730 per 100,000 in 2010; other estimates, like that of the Pew Charitable Trusts in 2008, have found that more than 1% of Americans were behind bars). If these statistics are unsettling when viewed from a distance, the personal experience for formerly incarcerated people is another story entirely. Derek Kelly, a Bronx native and West Harlem resident now building a new life after 25 years in the system, spoke movingly of the benefits of his newfound home, the Fortune Society’s Castle Gardens. Living since 2013 in a microunit (a term he prefers to “studio”) in this multi-award-winning 2010 building designed by Curtis + Ginsberg and developed by the Jonathan Rose Companies, Kelly provides living proof that the neighborhood’s initial resistance was an overreaction. As he pursues training in a substance-abuse counseling program and attends community meetings on-site, developing skills to help others find their way back from comparable troubles, he finds that the building answers his needs in ways he would never have expected. Its detailing is not perfect – he wryly noted that the ventilation system could be better suited to someone honing his skills as a cook – but its natural light, views, and accessible green roof strike him and his fellow residents as enormous advantages for people working to create a second chance within civil society. Some social institutions seem bent on dehumanizing people; Kelly’s experience hints at what is possible when the elements of design are focused on healing.

Bill Millard is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in Oculus, Icon, The Architect’s Newspaper, and other publications.

Event: Supportive Housing: Buildings Rebuilding Lives

Location: Center for Architecture, 04.14.2015

Speakers: Elissa Winzelberg, FAIA, Director of Design and Construction, Common Ground; Jonathan Kirschenfeld, AIA, Founder, Institute for Public Architecture, and Principal, Jonathan Kirschenfeld Architect PC; Emily Lehman, Deputy Director, Supportive Housing Loan Program, NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development; Derek Kelly, Resident, Fortune Society’s Castle Garden Supportive Housing Program; Nicole Branca, Deputy Executive Director, Supportive Housing Network of New York (moderator)

Organizers: AIANY Housing Committee

Sponsors: J. P. Morgan Chase