I live in Brooklyn, a couple of blocks from the Prospect Expressway, a 2.3-mile link between the elevated Gowanus Expressway and Frederick Law Olmsted’s Ocean Parkway. What I realized just looking out my bedroom window is that the sunken, six-lane expressway doubles as a swath of open space, affording me an unobstructed view of the Manhattan skyline from my fourth-floor walkup. But that open space, even if it’s filled by bumper-to-bumper traffic, is also—potentially—land.

Over half a century ago, Robert Moses rammed his highways through block after block of apartments, displacing thousands of families in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens, destroying some neighborhoods, and isolating others. He left New York City with over 160 miles of expressways and parkways, much of it heavily trafficked and desperately in need of rehabilitation. He also gave us a gift, a surprising one we don’t generally appreciate or notice.

The highways that carved up our densely developed urban neighborhoods were once the height of progress, the apex of mid-20th-century notions about personal transportation. But the rights-of-way created for those same highways could become the symbols of a 21st-century renaissance, one in which we repurpose what we’ve got to get what we need.

In short, highways are open space. Highways are land. And, like other kinds of open space land, they don’t need to be used for the same purpose forever. This is not a new concept or even a particularly radical one.

The Bloomberg Administration’s PlaNYC 2030: A Greater, Greener New York, released in 2007, advocated decking over rail yards and highways to create more room for housing. In Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens, where the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) runs through a trench that isolates the neighborhoods of Red Hook and the Columbia Street Waterfront, the report suggested, “A platform could be constructed over the below-grade section of the BQE to create nine new blocks of housing while reconnecting two neighborhoods.”

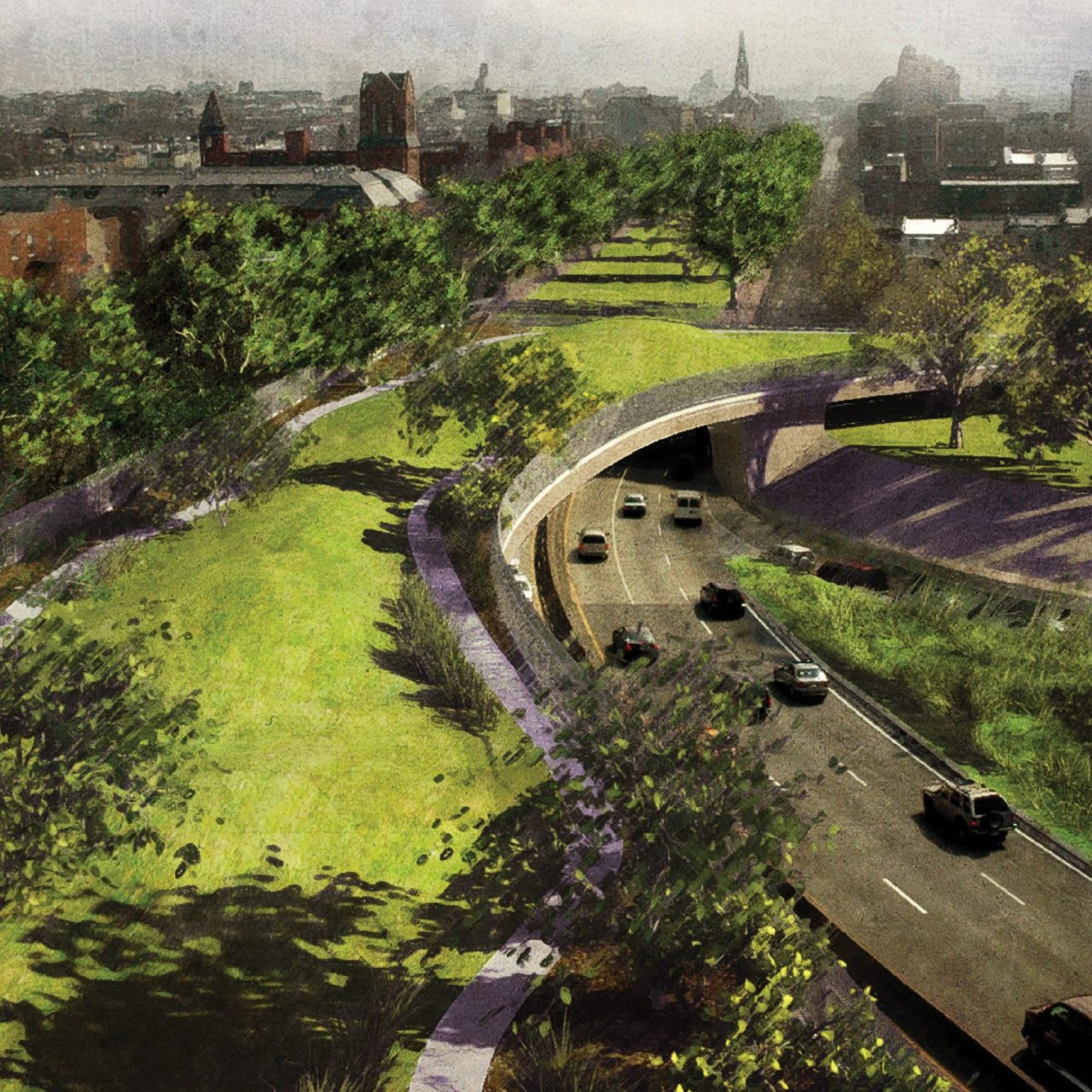

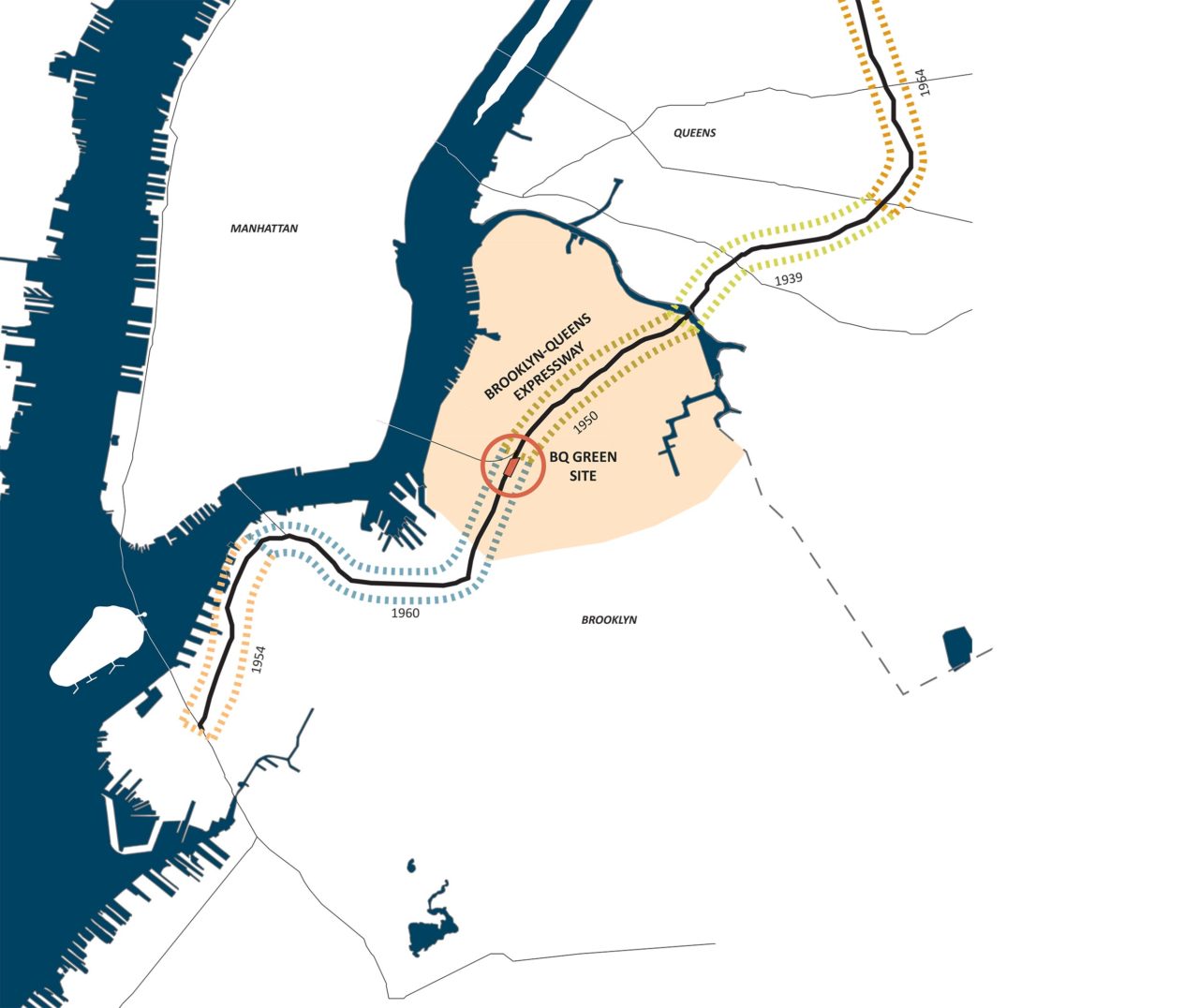

About the same time, DLand Studio, a Brooklyn-based multidisciplinary firm with an interest in public landscapes, began working on an effort called BQ Green to transform the BQE into “an ecologically and socially productive spine by introducing recreation space, ecological strategies, and infrastructure improvements.” DLand Founding Principal Susannah Drake worked closely with a City Councilwoman Diana Reyna to develop a pilot project that involved capping a two-block stretch in Williamsburg to “provide playing fields and verdant open space for an underserved Hispanic community.” As Drake recalls, “Our original budget of $100 million to provide significant open space and safer connections to school for the 140,000 Latino families seemed like a social and political win.” The project remains unbuilt.

More recently, in 2019, the highway became a hot topic when it appeared that New York City Department of Transportation (NYC DOT) intended to reconstruct the road’s triple-decker section that hugs the perimeter of Brooklyn Heights. The DOT proposed that the highway be repaired by building a six-lane “bypass” that would elevate all the highway’s traffic, 153,000 vehicles a day, to the level of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, a cherished park with a spectacular waterfront view that deftly conceals the highway. (The idea of capping this section of highway with a park go back to the 1940s, meaning that Moses could sometimes be astonishingly ahead of his time.)

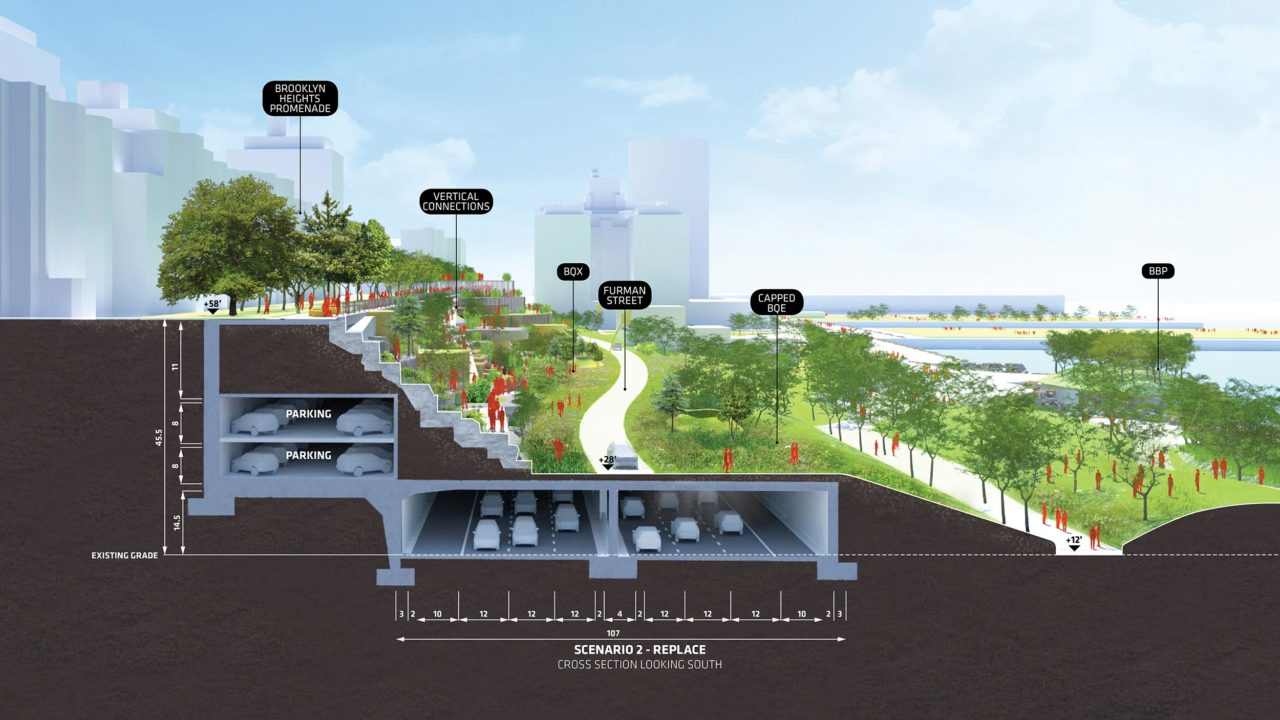

The DOT’s reconstruction strategy meant there would be no park for the duration of the project, and that the Brooklyn Heights residents whose homes overlook the harbor and the East River would be looking directly out on to multiple lanes of traffic for the six scheduled years of construction or, most likely, a lot longer. The sheer horror of the DOT’s plan sparked creative thinking and an embrace of alternative plans, including one from the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), whose New York office in DUMBO, not far from the BQE. BIG’s answer: run the highway traffic at grade along Furman Street, a wide, lightly traveled road that currently separates the cantilevered BQE from the Brooklyn Bridge Park. Then blanket the new highway route with a grassy deck, an extension of the waterfront park, connecting it to a reconstructed version of the cliff that existed prior to the construction of the BQE. Most intriguingly, the plan suggests that the decked-over stretch of highway could be “the beginnings of a linear park,” a greenway with room for a new streetcar line or bus rapid transit lane that would tie the borough’s waterfront neighborhoods together. In August, the de Blasio Administration essentially threw up its hands, announcing its intention to do some minor repair work on the highway and leave the big job for some future administration.

Even if its approach to repairing the BQE is never implemented, however, a report drafted by BIG team, led by landscape architect Autumn Visconti, did us a favor by leading with precisely the right question: “How can aging infrastructure be turned into an urban opportunity?”

The answer to that question is unlikely to come from Washington, DC. Congress did somehow manage this year to pass an infrastructure bill, one that will devote the lion’s share of funding, $110 billion, to repairing aging highways and bridges.

(It also includes $39 billion for public transit and $66 billion for improvements to passenger and freight rail.) What’s lacking in this year’s bill in general, and in governmental thinking across the board, is the vision to answer questions like the one posed by BIG.

Back when the Obama Administration was young and full of potential, I’d hoped that kind of vision would emerge. At the time, I thought we should reexamine the 46,000-plus miles of highways that were built beginning when President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which was paid for almost entirely by the federal government.

I began to regard the nation’s highways as a network that handily connects all our country’s population centers, a network that could be repurposed for uses that were unimaginable in the 1950s. The nearly 2 million acres of asphalt, instead of just being conduits for cars and trucks, could be, say, the backbone of a new high-speed rail network, one that doesn’t rely on freight railroads for right-of-way. Highway exits that are currently amorphous clumps of truck stops, gas stations, and motels could be developed into new transit-oriented cities full of affordable new housing, ones that are hospitable to bicyclists and pedestrians. But for that to happen, we’d need to think about infrastructure differently, not as a set of discrete problems—highways, mass transit, the electrical grid, sidewalks, bike paths—but as one big, intertwined system. Once we start thinking that way, it might occur to us that we don’t have to replace today’s private cars with new, technologically advanced cars, electric ones or autonomous ones.

A concerted interdisciplinary effort might allow us to see infrastructure systematically, to rid ourselves of most private automobiles and, perhaps, come up with an efficient spoke-and-hub system for freight that radically reduces the number of trucks that move through our cities. (Maybe NY Representative Jerrold Nadler’s longtime obsession, a cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn, would be one place to start.) If we could do that, we’d suddenly have surplus land, even in our densest cities.

What could we do with all that land? In a recent conversation, landscape architect Martha Schwartz told me about a concept she’s been studying: the linear urban forest. The idea is that space currently used for vehicles could instead be planted with trees, lots of trees. Urban forests, she believes, would absorb carbon, but also substitute permeable surfaces for impermeable ones, absorbing stormwater and refreshing depleted aquifers.

But cities can’t just become forests, not if they still house large numbers of people. So it might be time to consider another radical idea, an old one. In June of 1968, the New York Times reported that the federal government had agreed to fund the Lindsay Administration’s plan for a linear city, an urban experiment built atop a proposed highway, the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway, which would link the Verrazano Bridge with Long Island.

The narrow development, six miles long, was supposed to include “schools for 20,000 intermediate and high school pupils, 6,000 housing units, a community college, a regional shopping center, and space for industry.” I recently saw a photo of a project model designed by the firm McMillan, Griffis, & Mileto. It showed a shimmering parade of exotically angular buildings. But what impressed me more than that tantalizing glimpse of a future that wasn’t destined to be was something I read in the Times story: this unbuilt project was the first time that three federal agencies—the departments of Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Health, Education and Welfare—had collaborated on a major urban highway project. The impressive thing is the image of the feds working in a creative, interdisciplinary, cooperative way with New York’s architects, engineers, and planners.

I remain seduced by the idea that highways, even ones that are still jammed with trucks and cars, can double as vacant lots just waiting to be developed. Better still, instead of repairing our aging, degraded highways and building parks or housing above them, we can simply shut them down. We then turn their endless corridors into things we’d rather have: new kinds of transportation, housing, parks, solar farms, linear neighborhoods… even forests. Yes, pulling the plug on our highways will be monumentally disruptive, but nowhere near as disruptive as pulling the plug on our planet.

—

Karrie Jacobs is a professional observer of the man-made landscape and has written about it for numerous publications, including Architect Magazine and Curbed. She’s also a faculty member at the School of Visual Arts’s MA program in design research, writing, and criticism.