Precarious. Fraught. Complicated. Those are a few ways to describe the balancing act architects employ when deciding which jobs to pursue, which to accept, and which to politely decline. Such decisions take place within a larger context of social, political, and economic uncertainty at a moment when social media can call attention to missteps and supercharge the consequences. Ethical concerns now encompass everything, including the type of building to be designed, the reputation of the client, the response of neighboring communities, the environmental impact, and the working conditions on-site.

“‘Design everywhere, for everyone’ is our mantra,” says Jonathan Marvel, FAIA, founding principal of Marvel. “But that doesn’t mean ‘everything for everyone,’” he adds. Like most architects, Marvel believes good design should be available to as many people as possible, not just to those with money or power. At the same time, the firm’s 13 partners need to decide how any particular project “aligns with our values, experience, and interests,” says Yadiel Rivera-Diaz, a Marvel partner and landscape architect. The partners meet weekly to make such decisions for the 150-person firm.

Marvel understands that architecture is a forward-looking profession, so he tries to go beyond the here-and-now demands of his practice. He says, “We look at the big picture and ask, ‘What does our planet need? What are the skill sets we should develop to position ourselves for such work?’” Rivera-Diaz explains, “Sometimes we invent a project or look for a competition that may be a long shot, but forces us to generate an in-house conversation about something new.” For example, the firm recently won a competition in Barcelona—with local firm Garcés-de Seta-Bonet—for the conversion of a decommissioned power plant into a hub for digital media.

Like most firms, Marvel follows the AIA’s Code of Ethics, updated in 2020, which prohibits members from “knowingly designing spaces intended for execution or torture, including prolonged solitary confinement.” As a result, the firm has not pursued any of the projects stemming from New York City’s efforts to close its sprawling incarceration complex on Rikers Island and build neighborhood jails. But it did design a municipal parking garage near Queens Borough Hall in Kew Gardens, adjacent to a new jail. While the facility serves the community in general, it is used by people working at the jail and was built by the city’s Department of Design and Construction using a new design-build delivery method. “We lost a project because some people associated us with the jail,” says Marvel. So even though the firm didn’t cross a red line, it stepped over what some might call a “purple line.”

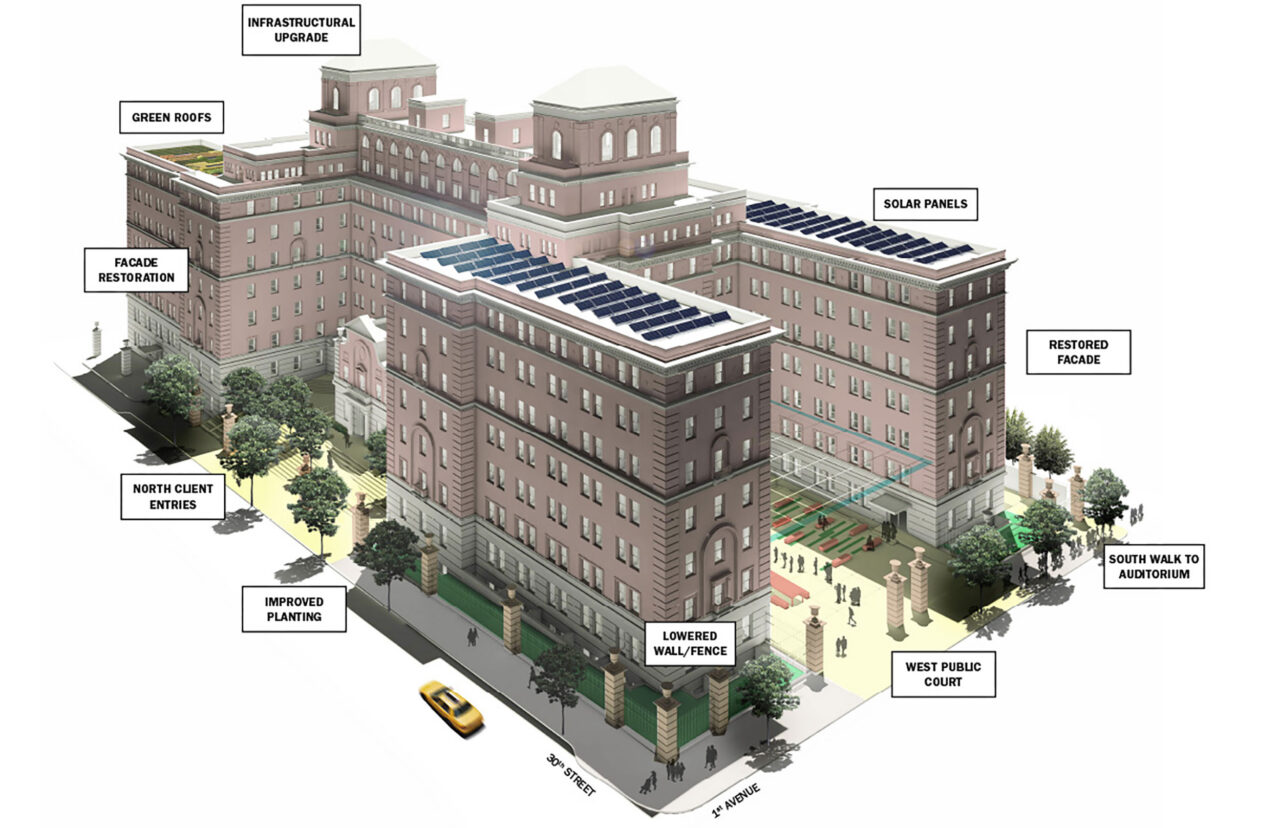

The company made a different decision when offered the chance to master plan a casino development on Coney Island. Although the partners wouldn’t rule out working on a casino project in the future, says Marvel, they believed the community’s opposition to and the particulars of the Coney Island plan made it wrong for the firm. The Coney Island Community Advisory Committee ended up rejecting the proposal in September 2025, and in December the New York State Gaming Facility Location Board did not include it as one of the three casinos it recommended for licensing. Sometimes design can be used to bridge divisions between opposing groups. For example, when Marvel was working on a master plan for the Bellevue Men’s Shelter near the hospital on First Avenue, it found that much of the community opposition to the project was about the long lines of people waiting on the sidewalk to be processed each day, not about the facility itself. So Marvel brought the waiting process indoors, resolving the issue for the community and creating a dry, protected space for the men checking in.

Based in Lower Manhattan, architect Daniel Libeskind is best known for his sculpturally expressive designs for the Jewish Museum Berlin, his addition to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and his master plan for the World Trade Center at Ground Zero. But, recently, Libeskind designed a pair of affordable housing projects for seniors—Atrium at Sumner in Brooklyn, and the Allan and Geraldine Rosenberg Residence in Freeport, on Long Island. Selfhelp Community Services, which provides support for aging adults, was involved in both projects, though the one in Brooklyn also included the NYC Department of Housing and the NYC Housing Development Corporation. Social housing is close to Libeskind’s heart, since he lived at the Amalgamated Housing Cooperative in the Bronx when his family first came to the U.S. “It was a five-story walk-up with no air-conditioning,” he remembers, “but it was a great place to live. It was about 90% immigrants.” Living there, he says, taught him that “creating communities through housing is a crucial idea of civilization.”

Libeskind had been in contact with Stuart Kaplan, the CEO of Selfhelp, and told him he would love to design a project for the non-profit organization. The first opportunity was the 45-unit project on Long Island, which serves low-income seniors and provides community space on the ground floor and recreation on the rooftop. The second was in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, where Libeskind designed an 11-story building that wraps around a central atrium and offers 132 apartments for low-income seniors and 57 units for seniors who had once been homeless. It also has social spaces and a health clinic for the community as a whole.

“I don’t think we would do a prison or an ICE detention facility or anything like that,” says Nina Libeskind, who co-founded the firm with her husband and oversees Studio Libeskind’s management. “We build projects that are meaningful to us, that are socially and culturally relevant,” she explains. The Libeskinds, though, note that the archetypes of prison, the hospital, and the school all emerged from the Enlightenment as institutions of reform, so each has a place in society. Having the right client is a key factor in the partners’ decision to take on a project. “It’s hard to build something enlightened for an unenlightened client,” says Nina. “It has to have the right karma,” adds Daniel.

In 2008, Daniel said at a speech in Northern Ireland that architects should be wary of doing projects in places like China and stated that he wouldn’t work for “totalitarian regimes.” Since then, his firm has designed a number of projects in Shanghai, Chengdu, and Wuhan for developers, but not the government. “The client has a lot to do with it,” he says. “It’s about having the freedom to create something genuine and not working under certain political restrictions,” he explains. “You have to find someone you feel is ethical,” adds Nina. “We’re lucky we can choose.”

As one of the founders of MASS Design Group, a rare non-profit design firm, Michael Murphy became known for projects that directly engaged issues of social justice or provided health and educational services to underserved communities in Africa, the Caribbean, and the U.S. Although he still sits on MASS’s board of trustees, he launched AMMA, “a collaborative studio working across design, architecture, planning, and public art” in 2024. As Murphy explains it, he felt frustrated by the limitations of the non-profit structure. Working for MASS on the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, he knew the properties around the project would increase in value as soon as the memorial opened. “I realized that if we don’t buy this land,” he says, “somebody else is going to develop it and extract value that we’re putting into the place.”

His new firm isn’t structured as a non-profit, so it can do things—such as take an equity stake in projects—that MASS cannot. “We can absorb capital, absorb investment, as well as do projects,” he explains about AMMA. “So we’re setting up a real-estate fund that will bring in different types of capital.”

AMMA designed the Oceana Innovation Hub in Barbados, an educational project that opened in 2025 and addresses issues of climate change in an island nation threatened by rising sea levels and increasingly powerful tropical storms. Using carbon-sequestering mass timber and a modular system of construction, the project was envisioned as a prototype that can be deployed around the island, the region, and eventually the world. Commissioned by the XQ Institute, the non-profit co-founded by Laurene Powell Jobs and Russlynn Ali, it is the first of three learning campuses to be built on the island. The larger goal is to support research, public programming, and entrepreneurial development in Barbados and the Caribbean. AMMA has “ownership in the prefabricated-module intellectual property,” says Murphy, “and we’re sharing ownership in the supply chain that we’re constructing” for the mass-timber modular system. “Unless we architects have an ownership stake, our agency is very weak.”

Instead of focusing on landing a particular job, Murphy believes architects should look at the system that generates projects and commissions. “I don’t think the fundamental question for architects is whether they should accept or reject a particular project,” he says. “The opportunities aren’t abundant anyway.” Instead, he proposes that “we transform the RFP process upstream. If we can do that, we can actually set the terms of what a project really is. We need to be proactive, more like an agent in what gets made.”

At MASS, Murphy did a number of projects in Rwanda, including the Nyarugenge District Hospital, the Butaro Health Campus, and the Mubuga Primary School. Although originally brought to Rwanda by Dr. Paul Farmer and his non-profit Partners in Health, MASS eventually did many of its projects there for Rwanda’s ministries of health and education, involving it with a government run by a strongman leader, Paul Kagame, who has jailed opposition figures. When asked about working in such a place, Murphy says, “In Rwanda, we were part of building some of the first pieces of infrastructure” that provided healthcare and schooling to people who had been devastated by a bloody civil war and decades of neglect. “The questions to ask are, ‘Where is the financing com-ing from, and what is the impact? Is the architecture being leveraged to transform systems, or is it being weaponized for another outcome?’” He also notes that architects “work in generational time, not political time. What we design today will be built in four or five years and will last many years more, when the political moment may have shifted.”

In addition to being careful about the kinds of buildings they design and whom they work for, architects are also asking questions about conditions on their building sites. The Architectural League of New York is currently collaborating with Construction Workers United (CWU), an initiative of the Worker’s Justice Project (WJP), on a call for design action to better protect workers on jobsites from actions by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). “Everyone benefits from safe and orderly construction sites,” says Jacob Moore, executive director of the league. “With our partners at CWU/WJP, we aim to support the important work that goes on at jobsites, intimately linked to every drawing an architect does, and to respect the workers charged with it.”

A design firm’s ethos often flows from its origins. “In terms of the type of practice we have, the inclusive nature of our culture, and the type of work we choose to do, a lot of it stems from the fact that we were founded by an immigrant with progressive social values,” says Kirsten Sibilia, managing partner at Dattner Architects, which today has about 140 employees and nine partners. (Richard Dattner, who founded the firm in 1964 and remains a partner, was born in Poland and raised in Cuba and the U.S.) “We think of the work we do as essential architecture,” says Sibilia. “It needs to be beautiful, sustainable, equitable. We don’t even talk about anything that doesn’t align with our values and our mission.” The firm has developed a reputation for designing affordable housing, public schools, and civic buildings.

Asked about the kind of work they won’t do, Sibilia says, “We look for projects that will have a positive impact on a community. So we don’t do casinos. We don’t do jails.” She notes, though, that the firm does do work for the court system and the police department, which sometimes includes holding cells. It is also doing a couple of ports of entry for the federal government, which have holding cells, too. It expects New York City to issue an RFP for a Department of Corrections training facility in College Point, Queens. The firm considered responding to it, says Sibilia, but decided not to. “The Department of Corrections isn’t an agency we felt would be a good client for us.” If it had been for the Police Department, the firm would have considered it, says Sibilia. “There is nuance to these discussions.”

While hot-button issues and political sensitivities change all the time, a firm’s values and culture should serve as an anchor for its decision-making process. At a moment when national policies on issues such as diversity, equity, and inclusion are being turned upside down and enforcement of immigration laws are being weaponized, architects need to steer their firms in a steady manner that leads to job portfolios they can be proud of for many years to come.

CLIFFORD A. PEARSON (“When to Say Yes”) is a contributing editor of Architectural Record and writes about architecture and culture for a range of publications. He is the co-editor (with Ken Yeang and Raghda AlHayali) of Tips From The Top: Architects Share Their Advice for Success and the co-author (with A. Eugene Kohn) of The World By Design.