“The students had to design their ethics, design their mission—they had to articulate it, explore it, and try to understand it. That was our base framing of the studio,” said Justin Garrett Moore, who with Alicia Olushola Ajayi taught “Mark-Marking and Place-Keeping: Erasure, Emergence, and Imagination” last spring at Columbia GSAPP, a studio that broke away from the traditional top-down assignment.

For Moore and Ajayi, the students each selected a site with a personal connection, and then dug deep into research to understand the layers of history and points of view around the site, beyond their own. What kind of design proposal might honor and acknowledge those perspectives? “The emphasis on data analysis and research into cultures and aspects of natural sciences really changed the way I thought about the project,” said studio member Tristan Schendel, who after graduating in May joined NYC-based firm Smith-Miller + Hawkinson.

In addition to this GSAPP studio, we checked in with other graduate studios at schools around the city, asking how the current conversations around social justice may have influenced student work in the 2020-21 academic year. Below we highlight a few outstanding projects that speak to issues of access and equity in thoughtful and engaging ways, with more work on view at oculus.aiany.org.

Alsharif Khaled Nahas (MArch ’21, Pratt)

Digging and Flying, Governors Island

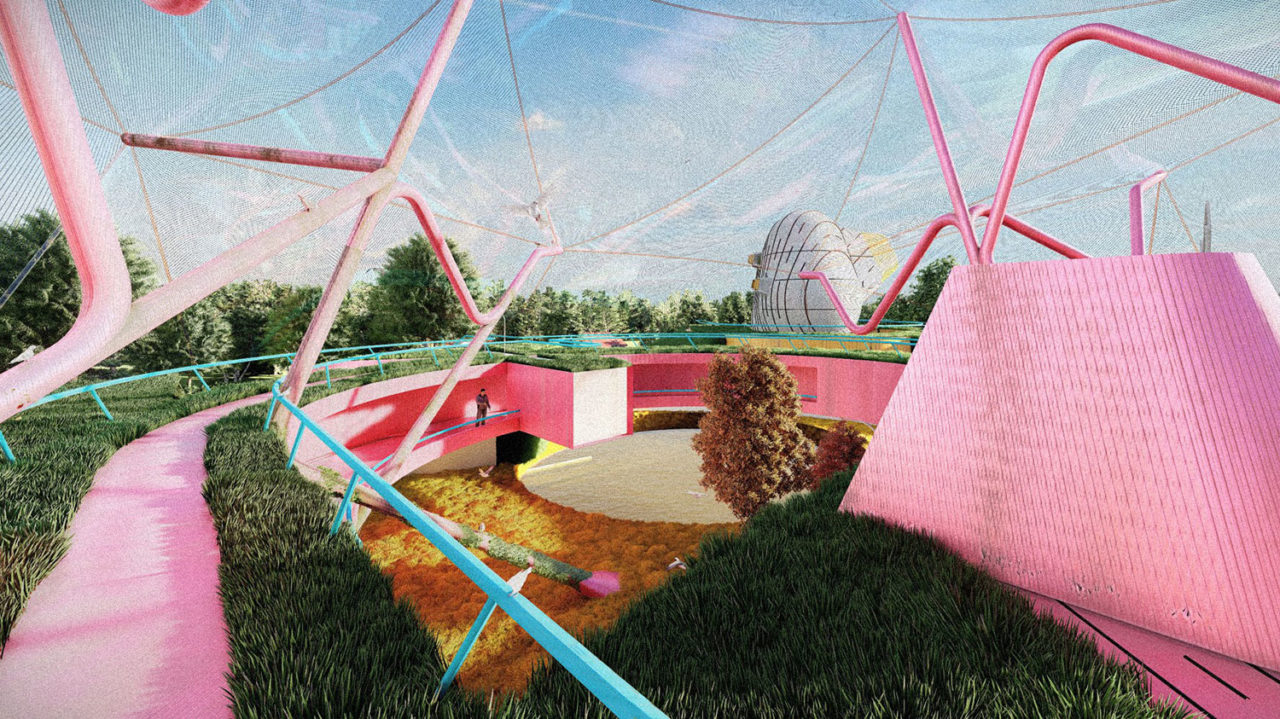

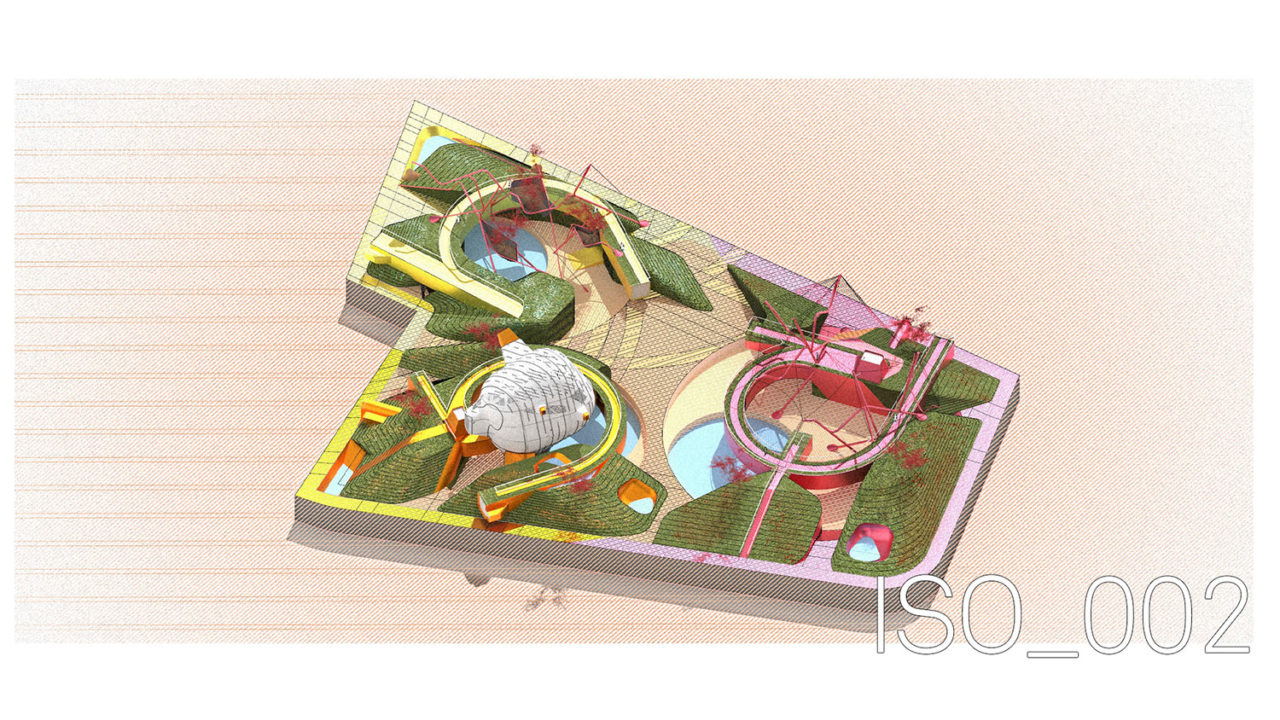

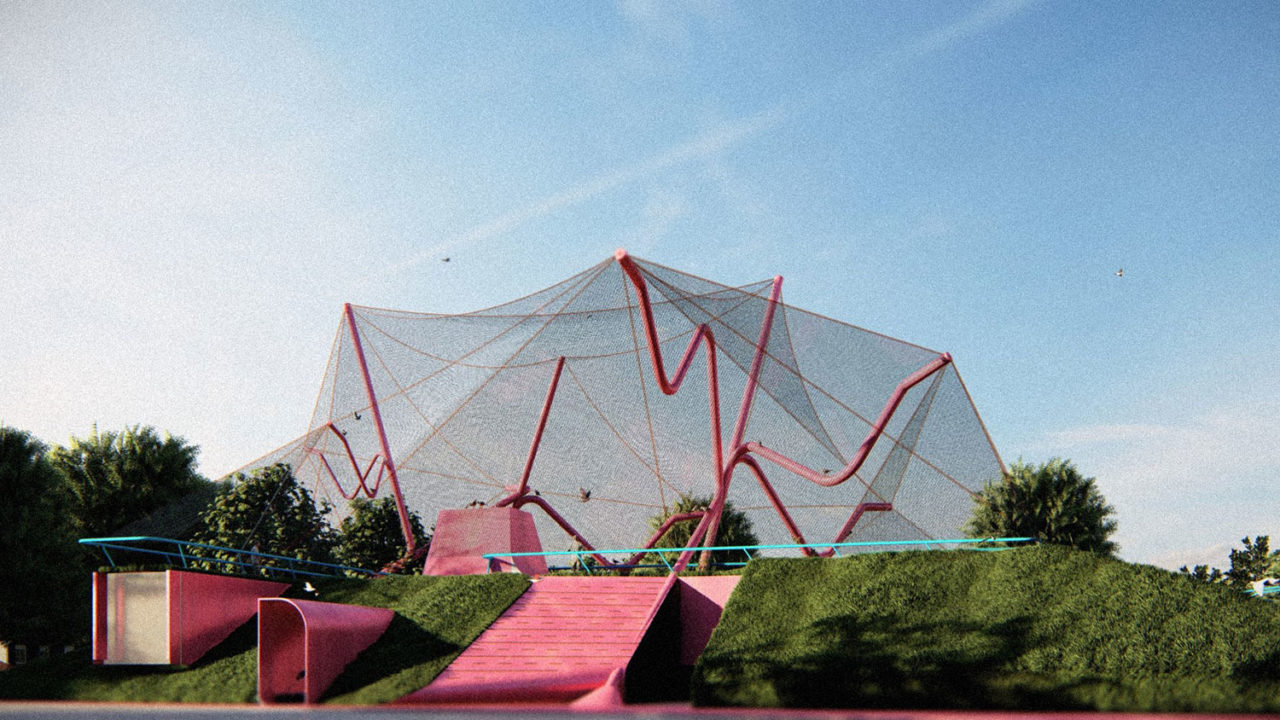

“According to conventional understanding, an aviary is a large enclosure for confining birds for exhibition. This project drifts from the idea of a cage, becoming a haven where birds come and go as they wish. The aviary’s form originates from a field of points, lines, vectors, and geometric curves that shapes the ground plane into separate elevated courtyards for dovecote, sanctuary, and nesting functions. A superstructure erected in each zone is expressed uniquely by material, color, projections, and spatial qualities that respond to programmatic needs and dramatize architecture’s responsibility to mediate between earth and sky.”

The project represents an operation of controlling curves, offsets, radii, line weights, colors, types, and profiles in the 2D realm, instead of cutting the model. A series of lines are extracted and offset from neighboring parcels to establish a grid system that acts as a field, and the field superimposes 2D and 3D geometries to kick off the form-making process—site planning as a kind of graphic design procedure.

Kay KoFong Hsia and Ye Lyu (MArch ’21, Pratt)

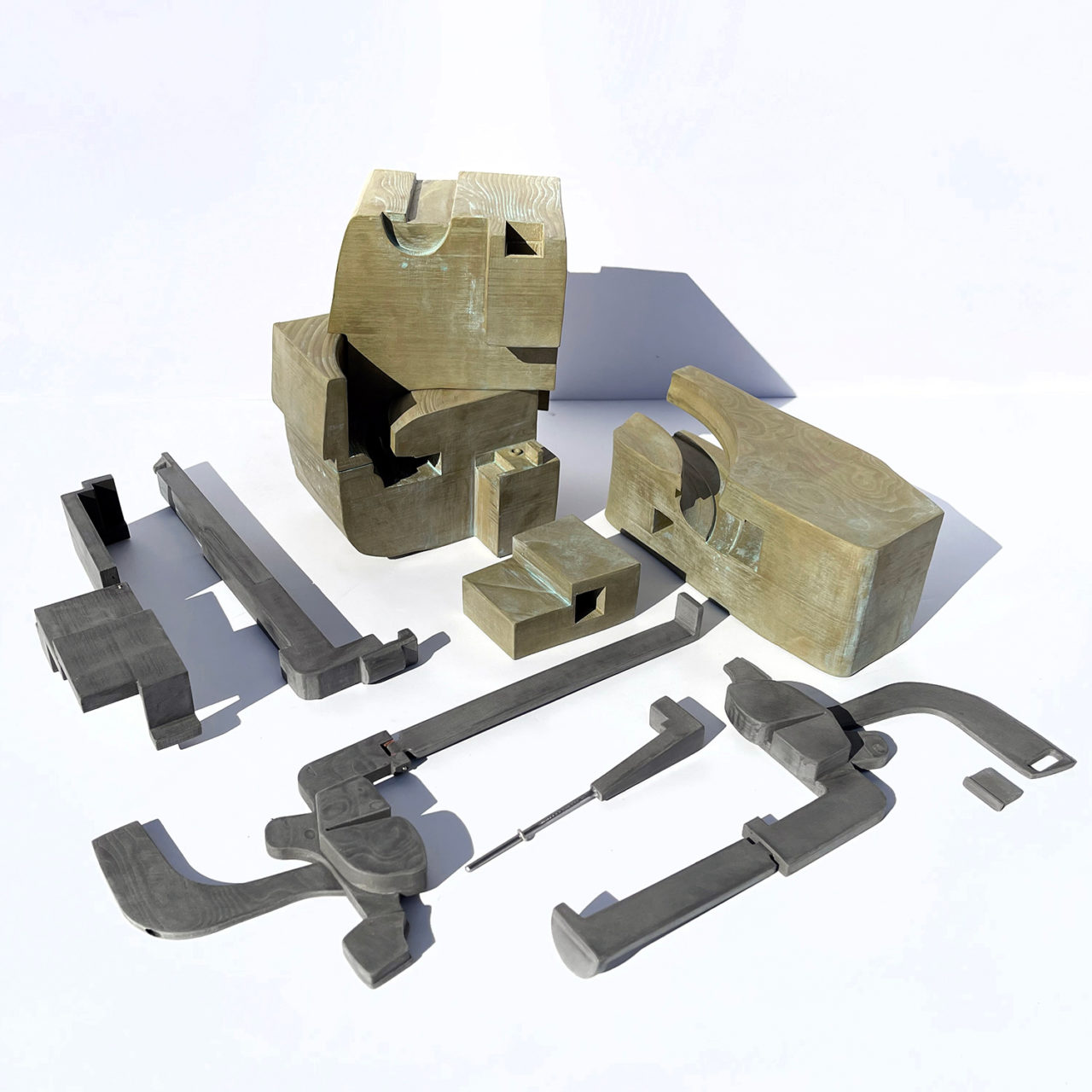

Puzzling Immersion: A New Form of Nature History Museum, Los Angeles

“Taylor Yard is a post-industrial site next to the Los Angeles River that has been polluted over years of different uses. Our proposed natural history museum aims to bring the public back to the presumably uninhabitable location. A series of carefully arranged gaps and apertures in section lead the landscape into the building and create several access points for experiencing the interiors while the building remains closed. Instead of abandoning the space or covering it with newer construction, this project treats site cleanup as a geological survey in which toxicity is part of LA’s history.”

The project proposes the spatial arrangement of the museum as a 3D puzzle. The interlocking nature of the puzzle assembly echoes how nature itself is a system of interlocking networks.

Soh Hee Oh (MArch ’21, Pratt)

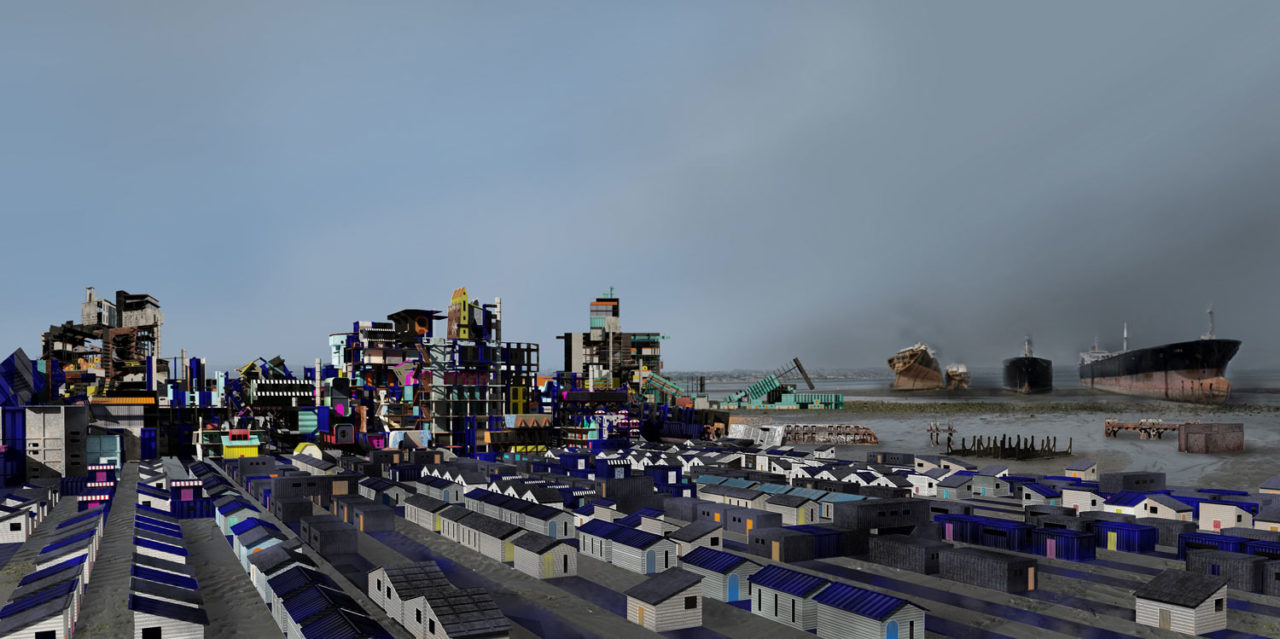

Ship Break Through

“As unregulated disposal facilities, shipbreaking yards are sites of mutual harm to the environment and human laborers. Ship Break Through reimagines shipbreaking yards as places where the 600 million people displaced by rising sea levels can build new cities. These coastal graveyards would be a resource for communities on the edge, yielding novel forms and spatial opportunities in an uncertain new world.”

Ship Break Through envisions cities evolving according to the elements washed up by ocean currents, creating an unplanned urban fabric. Through cutting and excavating the recycled scraps, humans exert control over their environment as we once used trees and mines.

Luz Wallace (MArch ’21, Pratt)

What is a tree when there are none?

“What happens when the resource that gives us oxygen and life is depleted? Where will we end up as the wealthy purchase trees as trophies, and saltwater infiltration from rising seas kills the trees in our ever-expanding cities? Since our society is rooted in industrialization, this process will inform how we treat the remaining trees. Surviving large trees are lifted above flood zones into islands of nature; roots are all we see, as the tree canopy is encapsulated and no human is allowed above. The new highway is water infrastructure for tree resources. The infrastructure is vital to the assembly and transportation of trees, always keeping them in life support.”

This project envisions a post-Anthropocene world, in which the arboretum has become an industrialized facility for preserving and cultivating trees. Suspended above the ground plane, the arboretum transforms our present ground into the bottom of the ocean. The tree pod in the assembly line is shrink-wrapped and encased until it’s purchased and unwrapped at the destination.

Benjamin Smithers and Luz Wallace (MArch ’21, Pratt)

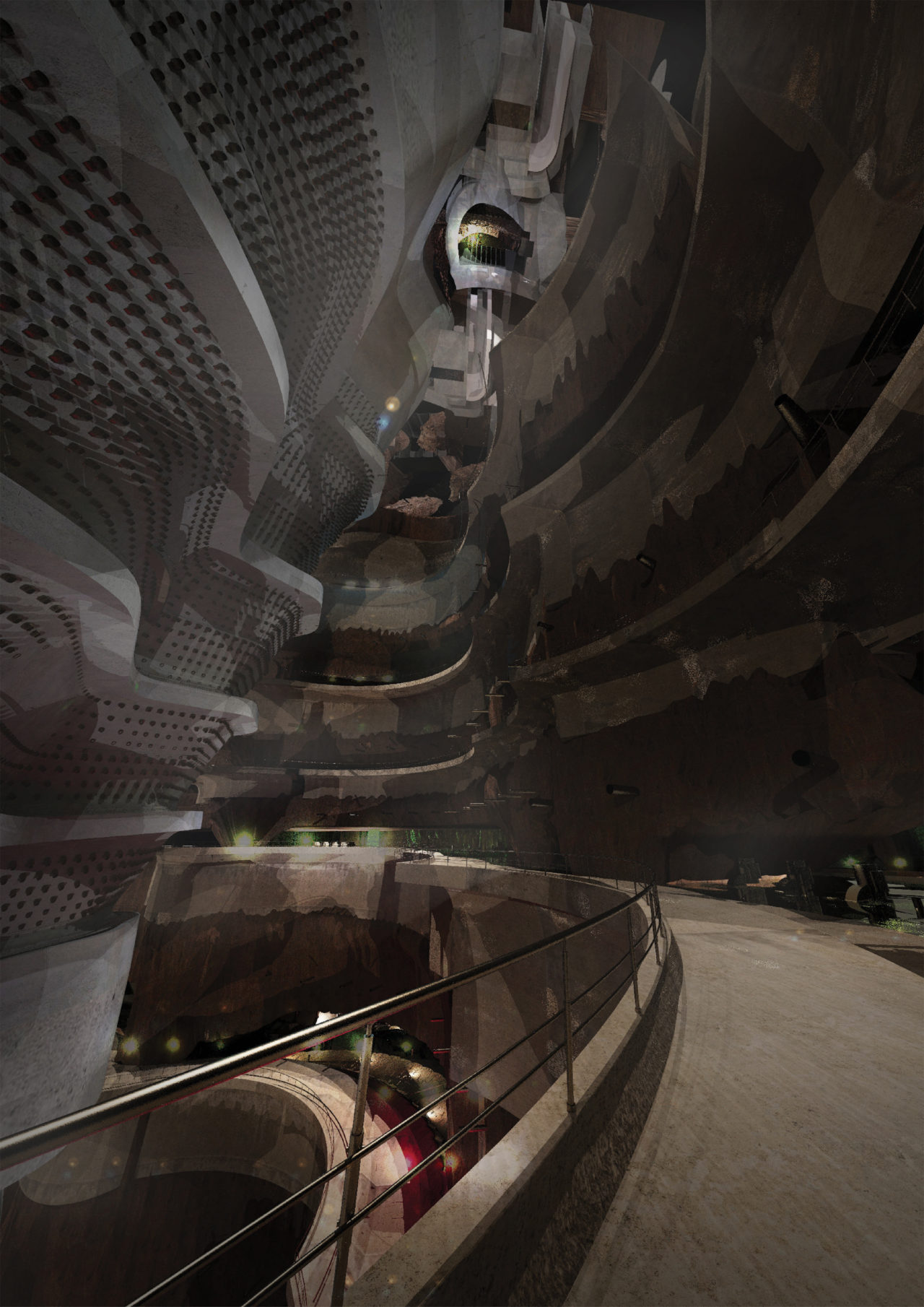

Awaiting the next violent refuse

“In the age of the Great Acceleration, when humans’ impact on the planet has increased in extent, magnitude, and reach, it is no longer credible to say there is any part of the globe that humankind has not altered in some significant way. Everything has become architecture. This project speculates on the architecture of a hypothetical abandoned mine, which we hybridized from real sites. It seeks to express the material qualities, agency, and other strange conditions produced above and below ground by the architecture of the Anthropocene.”

We cannot maintain the premise that we are separate from nature, looking on as mere observers of an untouched wonder. Nor can nature be seen as an outside resource for our exploitation. This project explores how architecture can engage a nature that is edited and altered by humankind to contribute to our understanding of this new reality.

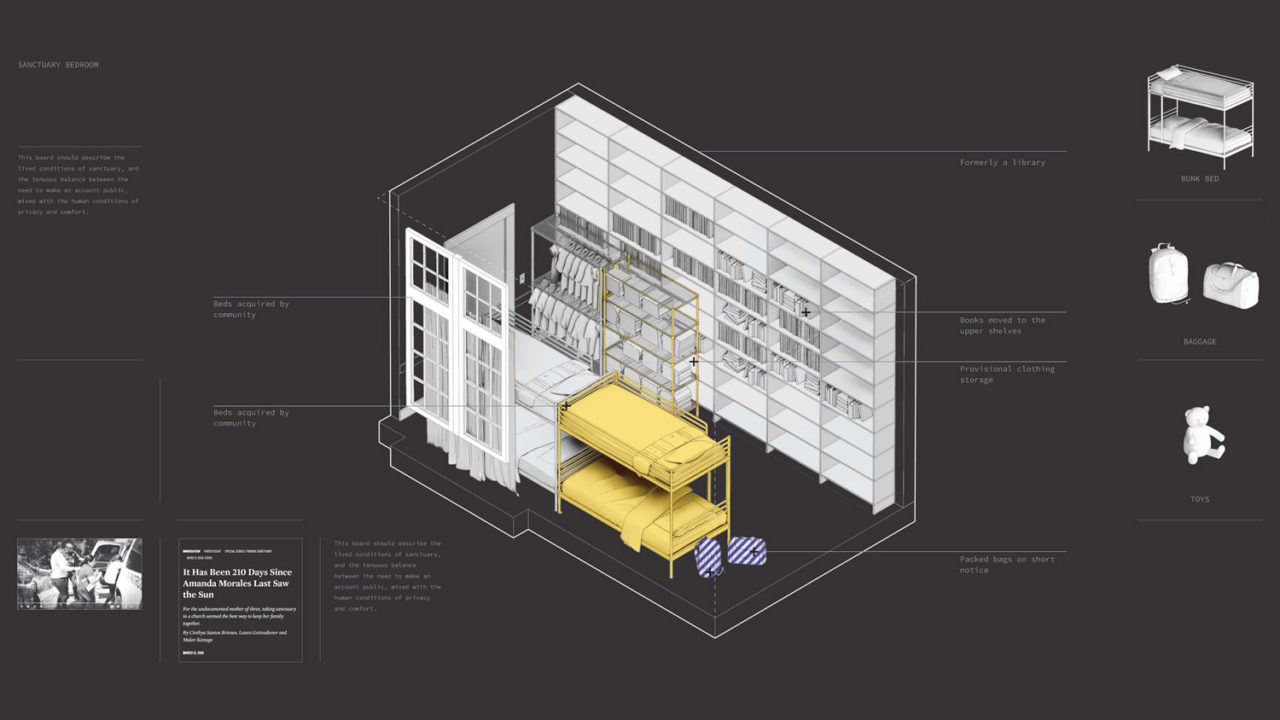

Austin McInnis and Yingxiao Chen (MArch ’21, Cooper Union)

Sanctuary Architecture

“The United States’s racist immigration policies acceleratingly criminalize, detain, and deport migrant bodies. While violations against migrants’ and refugees’ rights are most visible along national borders and airports, they extend deeper into cities, neighborhoods, public spaces, institutions, and homes. The urban sanctuary network embodies an organized refusal to collaborate with immigration enforcement agencies.”

In religious terms, “sanctuary” means to be “set apart.” In political movements, sanctuary refers to spaces of physical safety. In the United States, it can be traced to the stowaway houses and escape routes of the abolitionist movement.

Doosung Shin, Qicheng Wu (MARch ’21, Cooper Union)

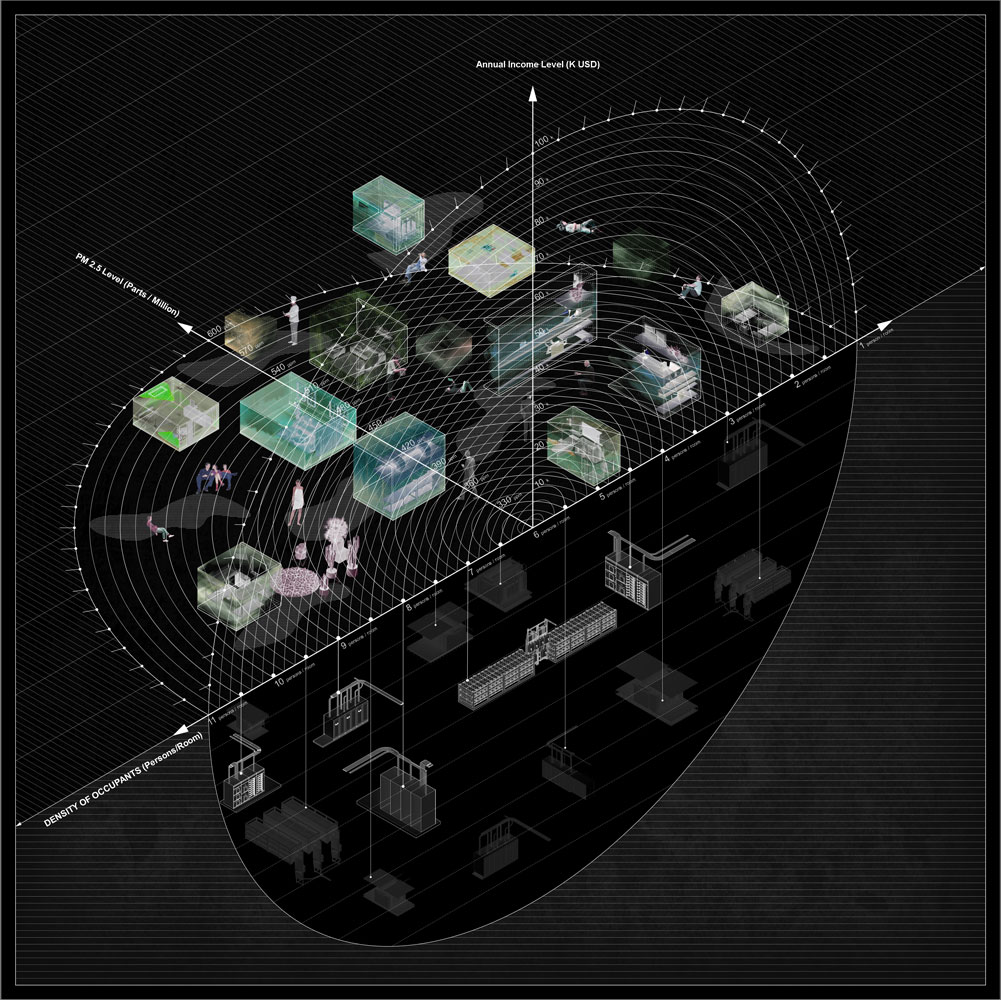

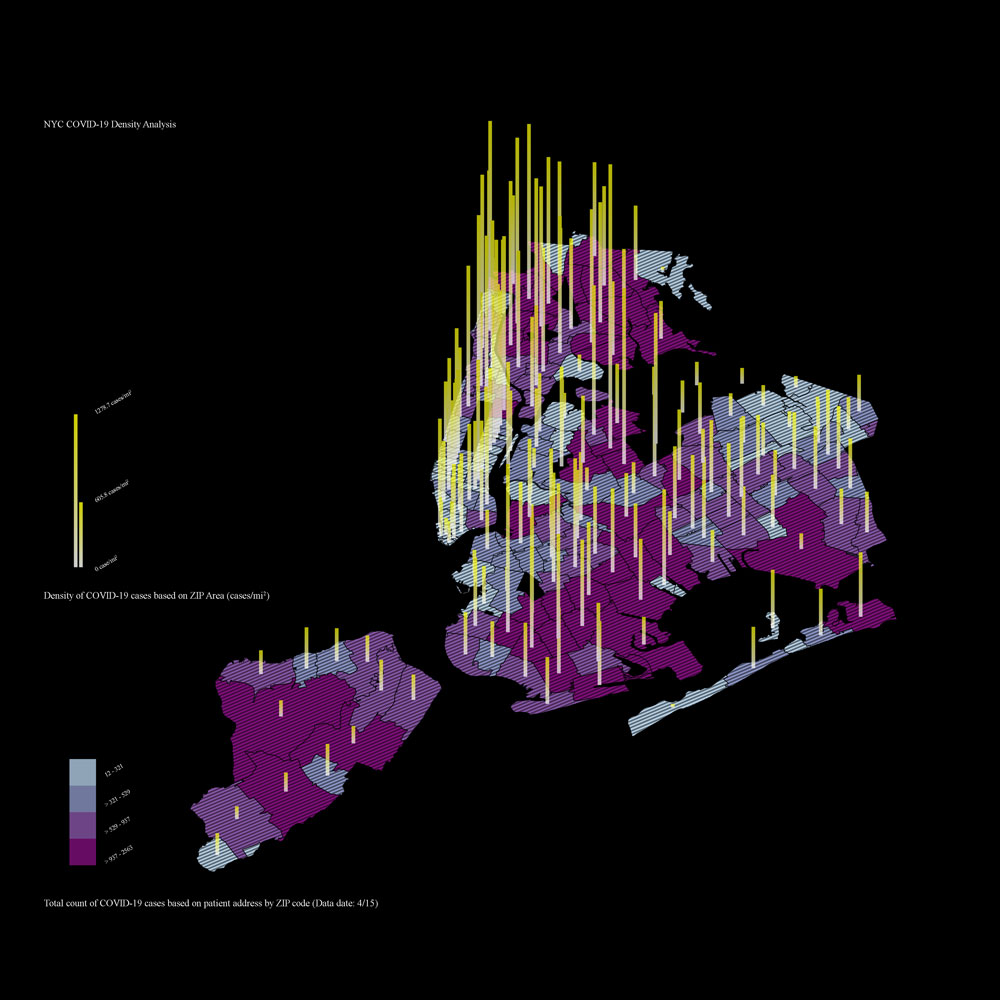

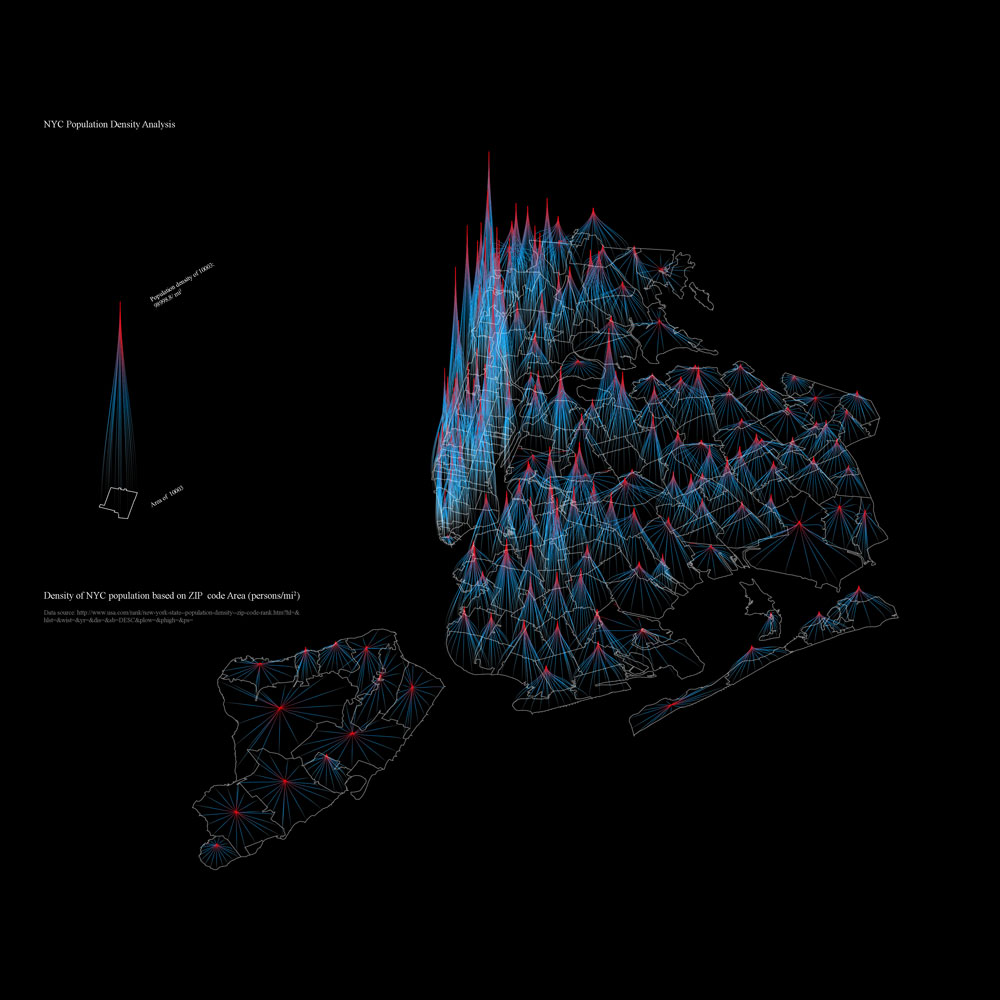

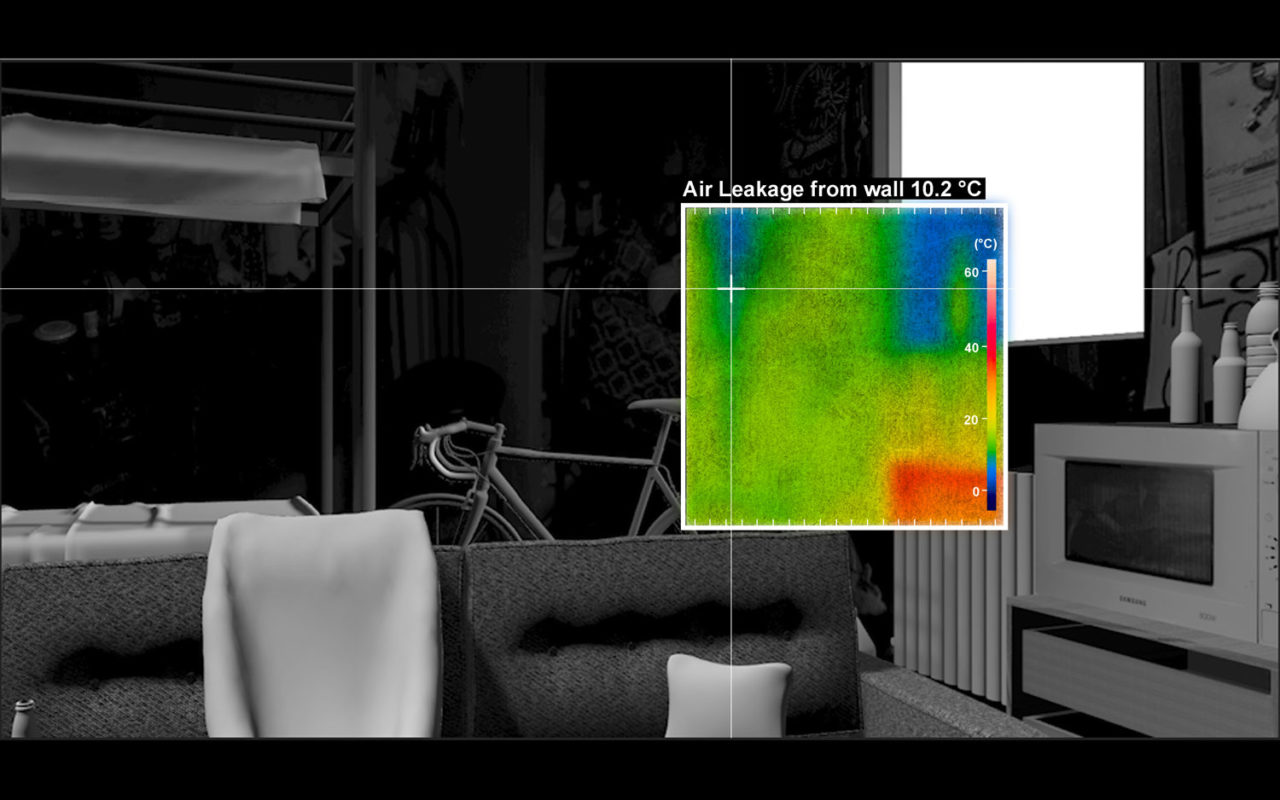

Microclimate: The Pandemic and Inequity

“In a lockdown, quarantine affects individuals living in diverse types of homes unequally. While one stays in a house with a backyard, another has been in isolation for months in a basement. Socioeconomics divide the present situation even more sharply. There are jobs that can be maintained from home, while others cannot; for some, fear of poverty is greater than fear of the virus. This project visualizes intangible discriminated microclimates as well as social and environmental inequality at three separate scales: the city, the housing unit, and the room/surface.”

To show how the virus discriminates, we researched climate in New York City under a lockdown situation at the macro, mezzo, and micro scales. A spherical-shaped coordinate system delineates the outer social and environmental conditions of microclimates, thus connecting three scales in one diagram.

Austin McInnis (MARch ’21, Cooper Union)

Facing the Street: Visions and Futures of Philadelphia, 1947–2035

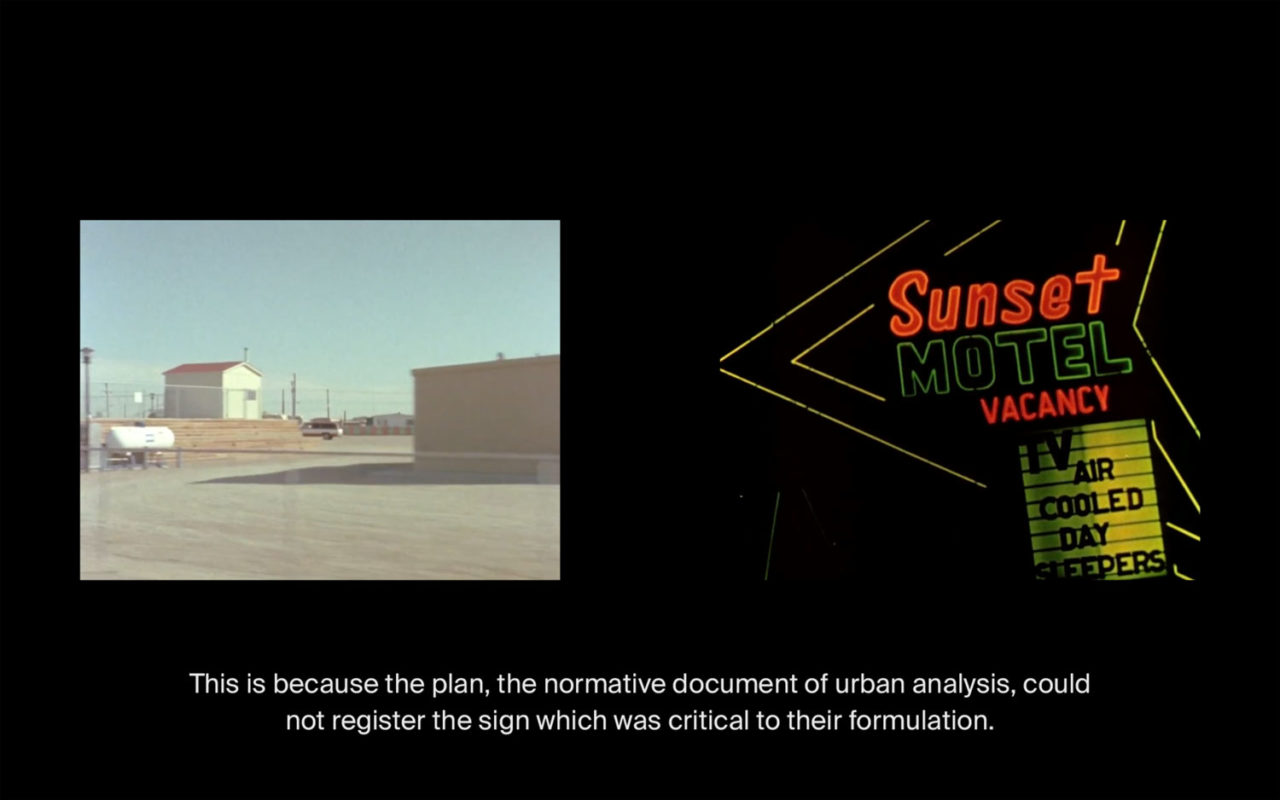

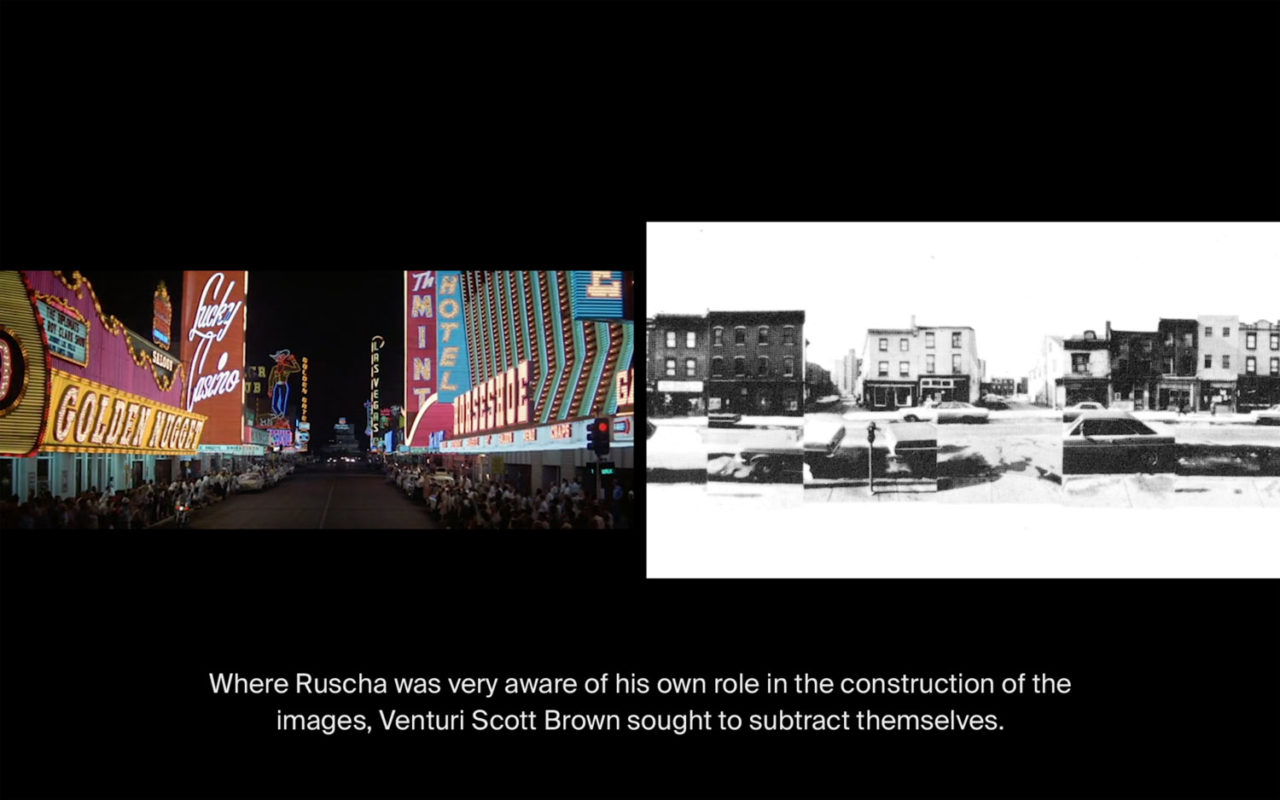

“Planners routinely propose methods for understanding site and conditions to justify their designs. The process produces an inherent resolution; it both inscribes the context and qualifies the architectural response. This thesis is concerned with the fidelity of acceptable devices used to research context, and the latent constructions of subject and fitness embedded within them.”

In Philadelphia, convincing the public of downtown automobile infrastructure had planners carefully calibrate a vision of universal access—at the expense of those drawn out and denied from their plans. Ultimately, this played out through the images, surfaces, and streets of the city.

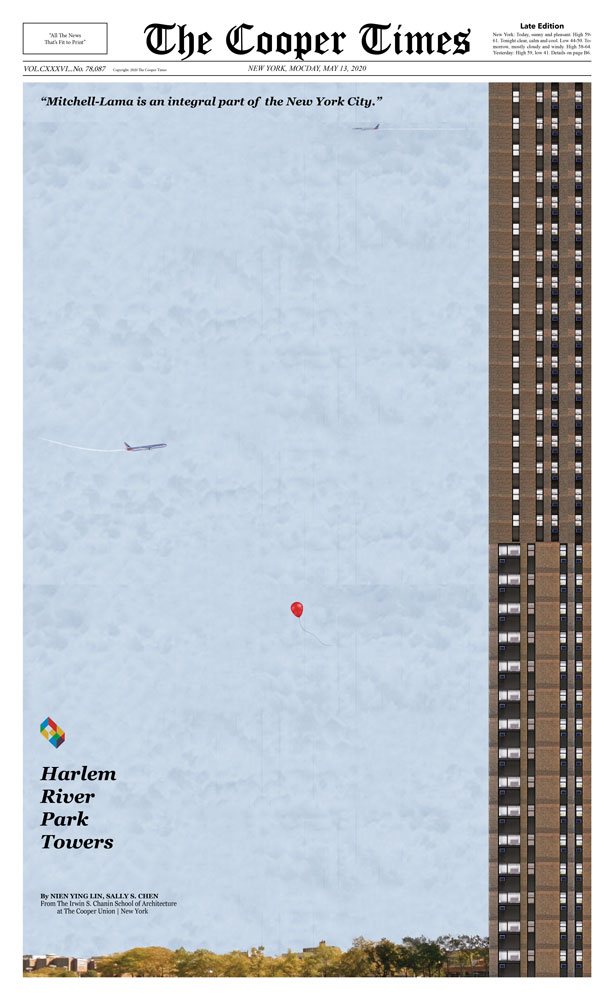

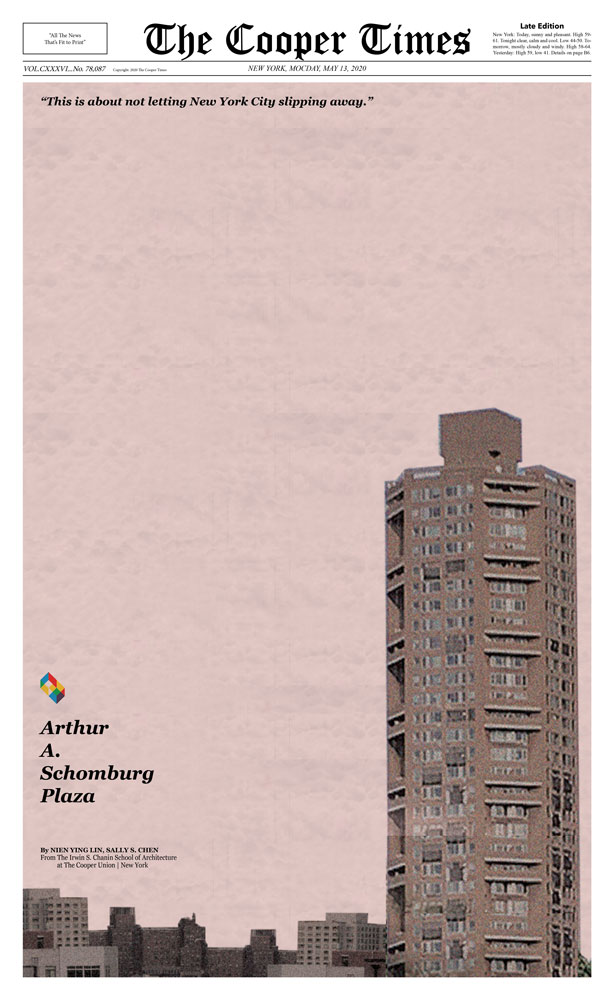

Sally Chen, Nienying Lin (MARch ’21, Cooper Union)

Deep Segregation

“The adage that New York City is a melting pot is misleading; so is the first impression of luxury shopping, glamorous hotels, and modern skyscrapers. Both images of the city obscure the complex, divergent, and rich daily lives lived by its inhabitants. An often-overlooked reality of living in New York exists in those buildings that make up the ‘background’ of many images of the city. Their residents are not extremely poor nor rich. They are families who occupy a tenuous middle—adjacent to, but set apart from, constructed illusions of what New York is believed to be, and the realities of its wealth and prosperity.”

Deep Segregation brings into view the architecturally invisibilized typology of high-rise residential towers developed mostly in 1970s New York for low-moderate and middle-income Black and Brown bodies under the Mitchell-Lama housing program. It interrogates the techniques, materials, and deeply entrenched forms of urban segregation formalized by the towers, but also chronicles the inventions, joys, pleasures, and challenges of those who have called and will continue to call them home.