Plans for rebuilding the World Trade Center, which began to emerge within days of September 11, 2001, have almost always included a place for performing arts. The intention was to make the 16-acre development (anchored by over 9 million square feet of offices) more than a 9-to-5 destination, and to provide a forwardlooking bookend to the retrospective 9/11 memorial and museum.

In early discussions, the World Trade Center Performing Arts Center (WTC PAC) was to have one or more resident companies. But over time, executives of the arts center, including its current president, Maggie Boepple, came to believe, she said, that “what NYC needed was a theater that commissioned new works.” She adds: “We persuaded the board that we should be a producing house and not a presenting house,” meaning that the WTC PAC wouldn’t be a home to other companies, but a creator of its own attractions. That approach, however, required a facility flexible enough to accommodate the needs of both traditional and experimental works of theater, opera, dance, music, and the Tribeca Film Festival, which is planning to use the building each spring.

Joshua Ramus, the architect chosen in 2015 to design the center (now known as the Perelman, for its lead donor, businessman and philanthropist Ronald O. Perelman), imagined a place where auditoriums of various sizes could be combined, and where even the circulation spaces between those auditoriums could be employed by production designers. “The ideal building can be used as a device to help bring people into the space of the performance, even before they get to their seats,” Ramus explains.

BEYOND THE BLANK SLATE

Founder of the Brooklyn firm REX, Ramus has had experience with flexibility: He collaborated with Rem Koolhaas of OMA on the Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre, a Dallas facility with a stage at ground level that can open up to the surrounding plaza, allowing not just the building, but its site, to be incorporated into productions. What the Wyly demonstrated, Ramus says, is that the old idea of flexibility just won’t cut it. That concept—really the Miesian idea of “universal space”—assumed the availability (and affordability) of stagehands needed to make the change from one configuration to another. “People think, make it a blank slate and it’s really flexible,” Ramus says, “but nobody has the operations budget for that kind of flexibility. So you do one thing, and it becomes the de facto permanent condition.”

A solution lies in the fact that it’s easier to raise money for buildings than for operations, as any development officer will attest. So an expensive building that can rearrange itself at the flick of a switch makes more sense than a less expensive building requiring stagehands to transform it. With labor costs high, “There is increased tension between operational costs and capital costs,” says Ramus. “We’re seeing that in every kind of cultural institution.” But architects, he says, “are only now responding with an updated notion of flexibility.”

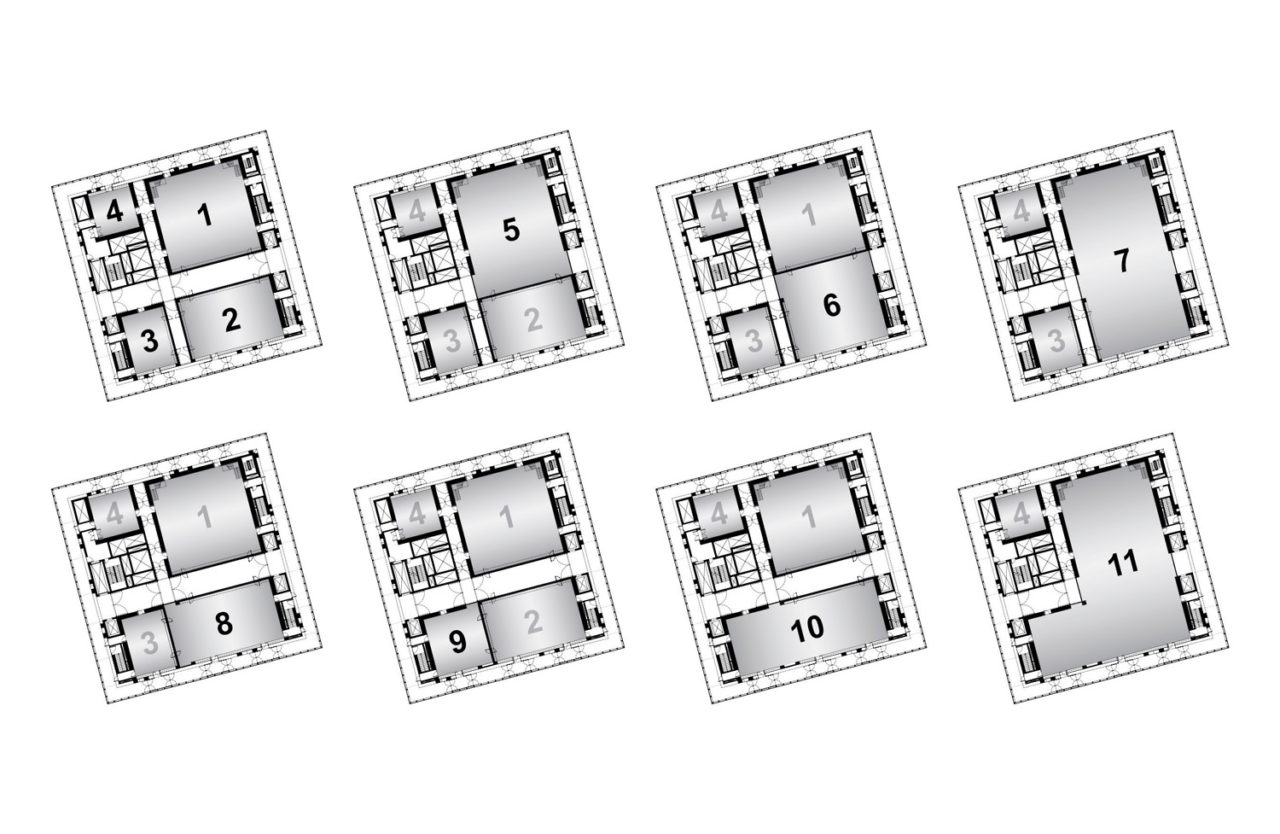

That notion, he says, involves providing “presets”—selected theater configurations known to have good sightlines and acoustics. “You invest in the capital costs to make sure you can move between the presets with minimal labor costs,” says Ramus. Directors will begin riffing off the presets, he says, so “if you do each of the presets really well, you get real flexibility.” At the Wyly, he reports, “we gave them three presets (proscenium, thrust, and flat floor), and during the first four years, they staged 28 productions in 25 unique configurations.” His conclusion?

“We proved the benefit of not providing ‘universal’ flexibility,’ which would have meant a black box that was too expensive to transform, but a more ‘tailored’ flexibility.”

At the Perelman, there will be several times as many presets as at the Wyly: 11 so far, with more to come as the building moves toward its projected 2020 completion. “It’s the original idea of the Wyly taken to the next level,” says Ramus, who worked with London-based theater consultants Charcoalblue on the design.

From the outside, the building appears to be a simple box, though an unusually elegant one: it will be clad in slices of translucent marble sandwiched between sheets of glass. (The building will glow at night like Gordon Bunshaft’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.)

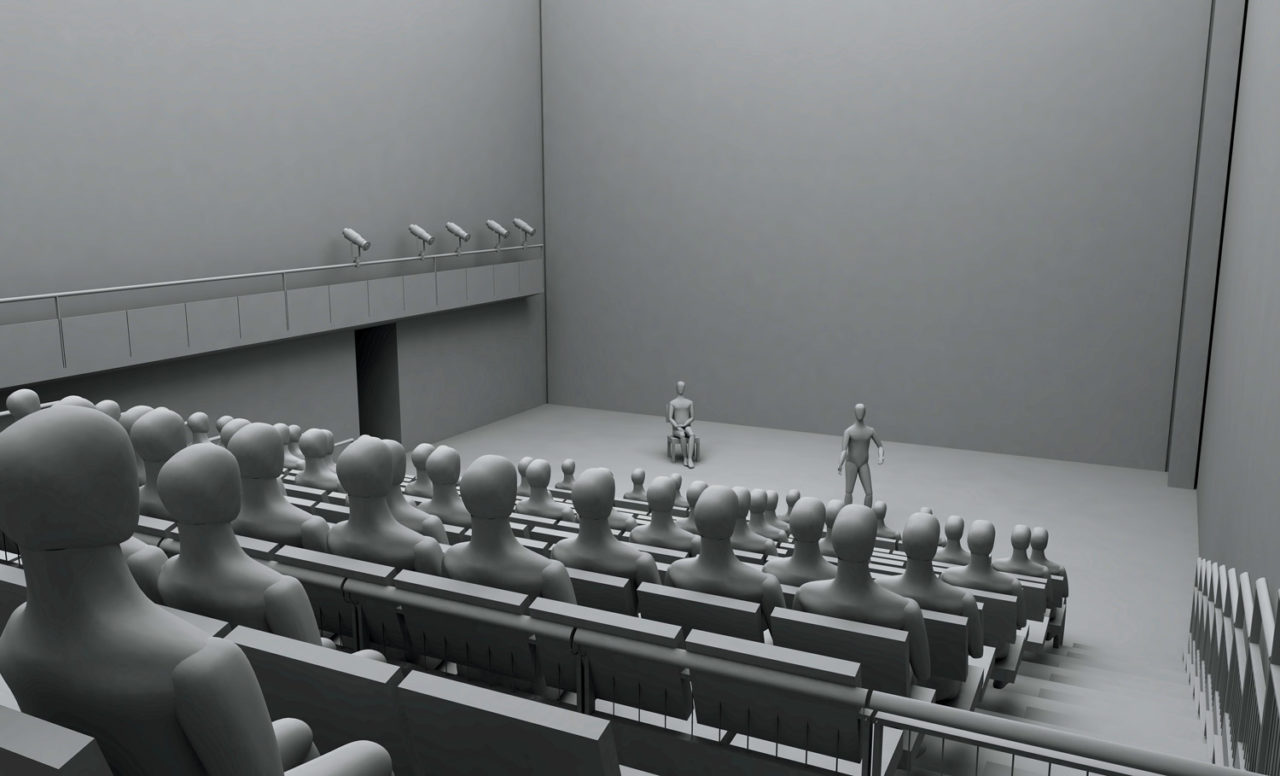

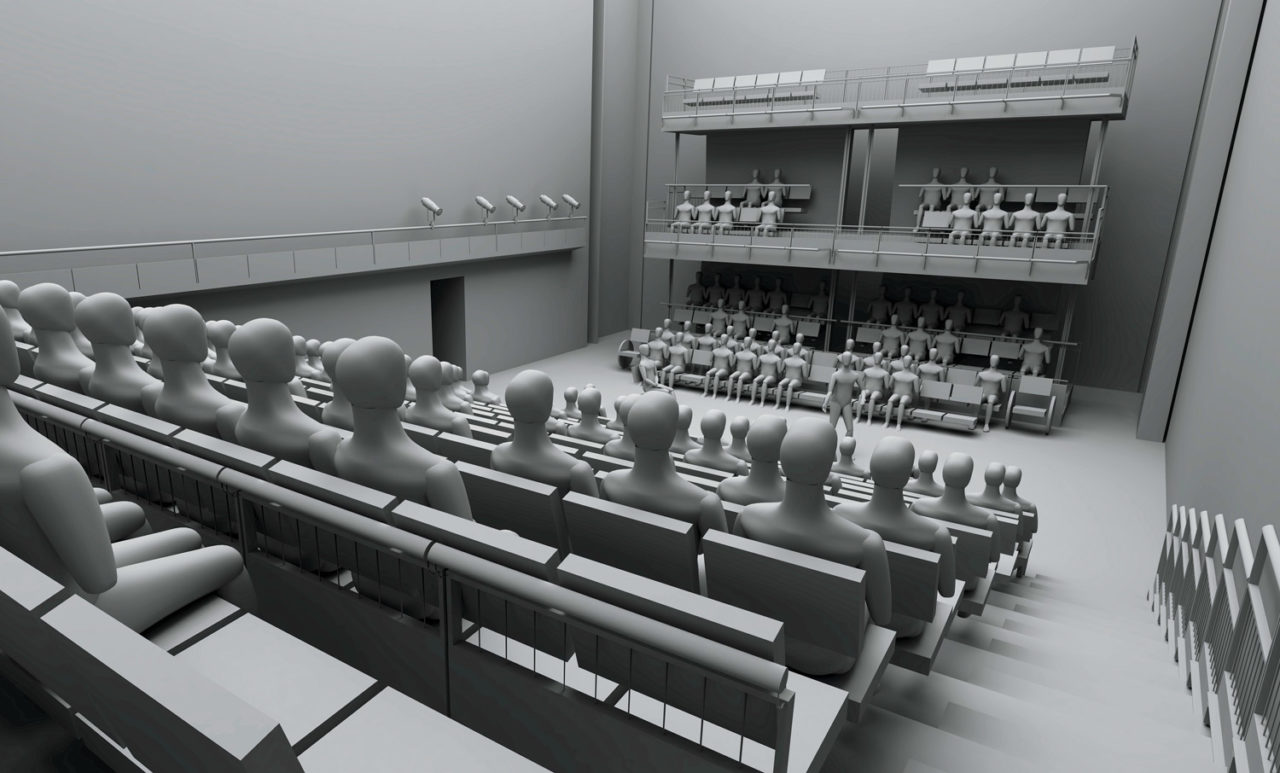

From the lobby, patrons will take stairs or elevators (arranged in four couplets, marked A through D) to a top floor, the “performance level,” containing the three theaters (with up to 99, 250, and 499 seats) and a small rehearsal hall.

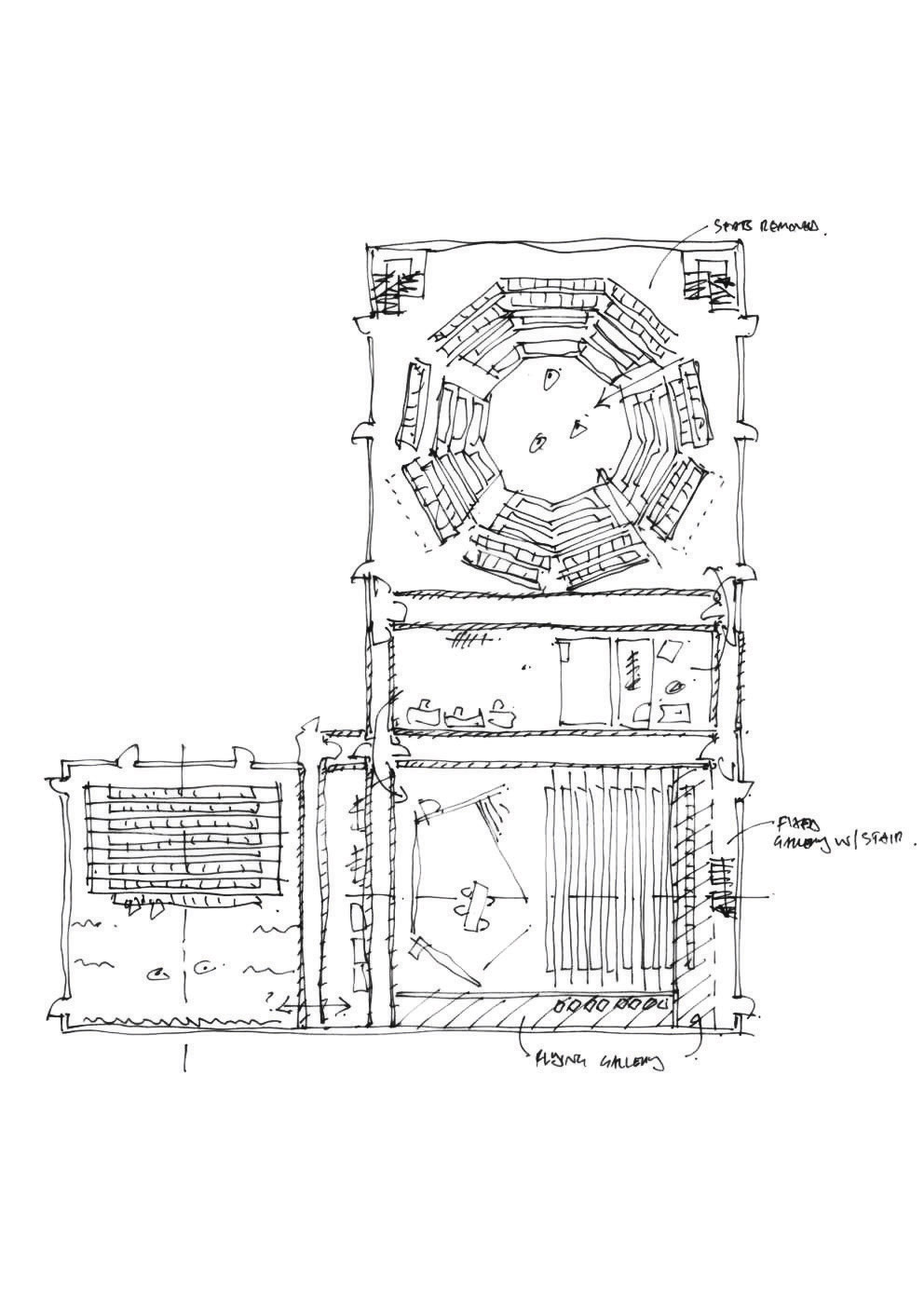

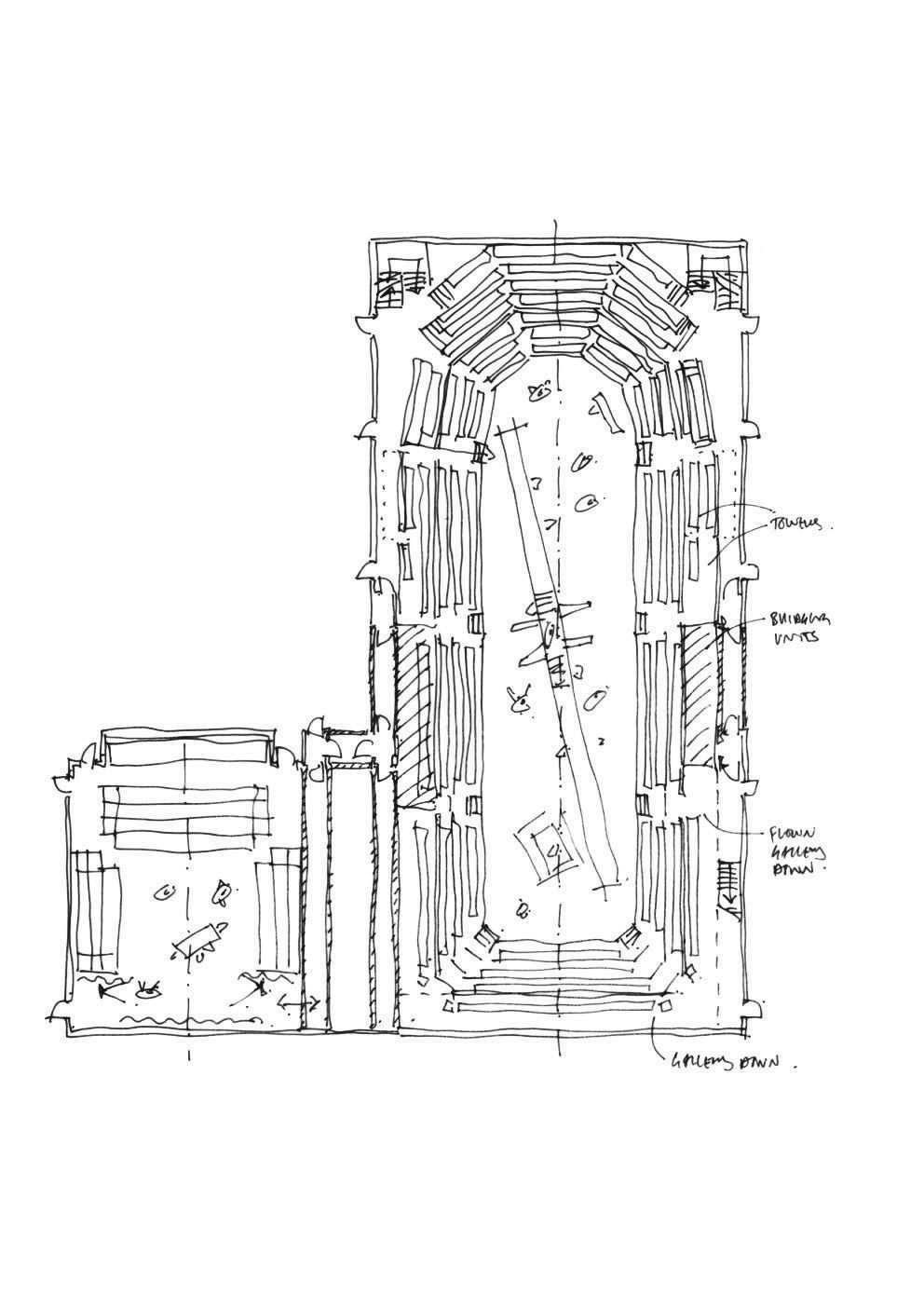

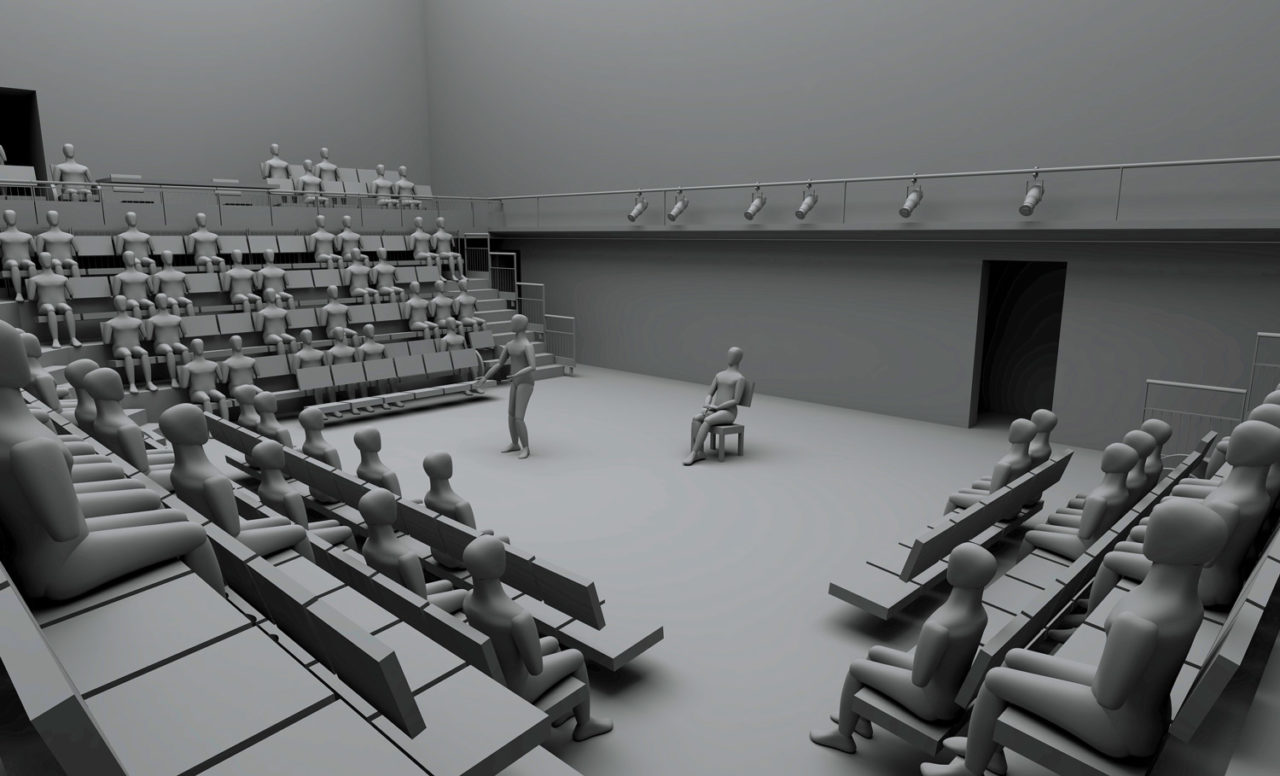

Those rooms are served by a continuous loop of circulation—essentially a perimeter hallway an amazing 78 feet high—and by two internal hallways that cross in the middle of the building. Each theater can take on multiple configurations, which are themselves impressively varied; the floor of the biggest room, for example, can descend into the space below to provide raked seating. But if that’s not enough, the “guillotine walls” that separate the theaters (already 43 feet high) can be lifted into the mechanical spaces above, turning two or three of the auditoriums into larger performance spaces that incorporate the hallway space between them, potentially seating 1,200.

DESIGNING A SEAMLESS EXPERIENCE

The ability to meld circulation spaces into the performance spaces is a feature Ramus is particularly proud of. “You can allow the public to encircle the auditorium, if that’s interesting,” he says. “Or if you think it’s important for the public to swarm the auditorium and move in from one direction, you can do that, too.” He adds, “You can use the interstitial spaces to put people into the context of the performance before the play begins.” Directors he has spoken to, he notes, believe that feature will facilitate their jobs, easing audiences’ “suspension of disbelief.”

In drawings, videos, and models in his DUMBO office, Ramus demonstrates some of the permutations, which involve moving not just walls, lights, and speakers, but catwalks and seating towers tall enough to incorporate multiple balconies. The systems needed to operate them include hydraulic lifts, electric motors, and, of course, computers.

“A person could come to a performance two weeks in a row and be in two very different buildings,” says Ramus. But how will patrons find their way around, with each configuration requiring different circulation routes? The solution is provided by baffles (nine-foot-high partitions that unfold from the perimeter of the buildings like shutters) that can be deployed to direct patrons and keep them from going astray.

Among the smaller problems the architects are dealing with is how to assign seat numbers: the same “physical” seat could be in very different positions for different performances.

Bigger challenges include emergency evacuation plans, which must ensure multiple means of egress no matter how the theaters are configured. According to Alysen Hiller Fiore, a REX director who is leading the project, “We had to get a series of temporary permits of assembly from the Quality Assurance Division of the Port Authority” so that theater administrators don’t have to apply for permits every time they change configurations. (The Port Authority, rather than New York City, has jurisdiction over the World Trade Center site.)

Though the building may look like a “dumb box,” Ramus says, it’s anything but. Inside it’s more like a Swiss watch, with countless moving parts. The goal is to produce a level of flexibility that will keep the Perelman’s creative team—and audiences—on their toes. “If we do this right,” Ramus says, “no one will have any idea how complicated it was.”