As the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the city in early September 2021, citywide flash flood alerts popped up on cell phones and were, for the most part, ignored. If you didn’t live near a river, what was the worry? In the end, the storm trapped dozens in basement apartments, killing 11. In the days following, the city returned to normal—or whatever we’re calling normal these days. Ida was a far smaller event than Superstorm Sandy, but the death toll from Ida was 46 in the metropolitan region; 44 died in the city during Sandy. The week Ida hit the city, however, 80 people died of COVID, so perhaps it’s no surprise that Ida was not a bigger news story, marshaling efforts to reimagine vulnerable waterfronts.

Dozens of interconnected systems played a part in creating the perfect storm to wipe out those apartments. The aging New York City sewer system, for one, cannot handle the increased amounts of rainwater. While the city is making strides with green roof and photovoltaic requirements for rooftops and climate resiliency initiatives, much attention has been focused on keeping ocean water out, rather than absorbing water that falls from above. Updating the city sewer system is an obvious remedy, but a network of “sponges” will also be needed. While concrete systems of infrastructure–both literal and figurative–remain important, from sewers to levees and water pumps, the infrastructure of the future will also need to be green, absorbent, and living. Infrastructure must rely on nature rather than attempt to control it.

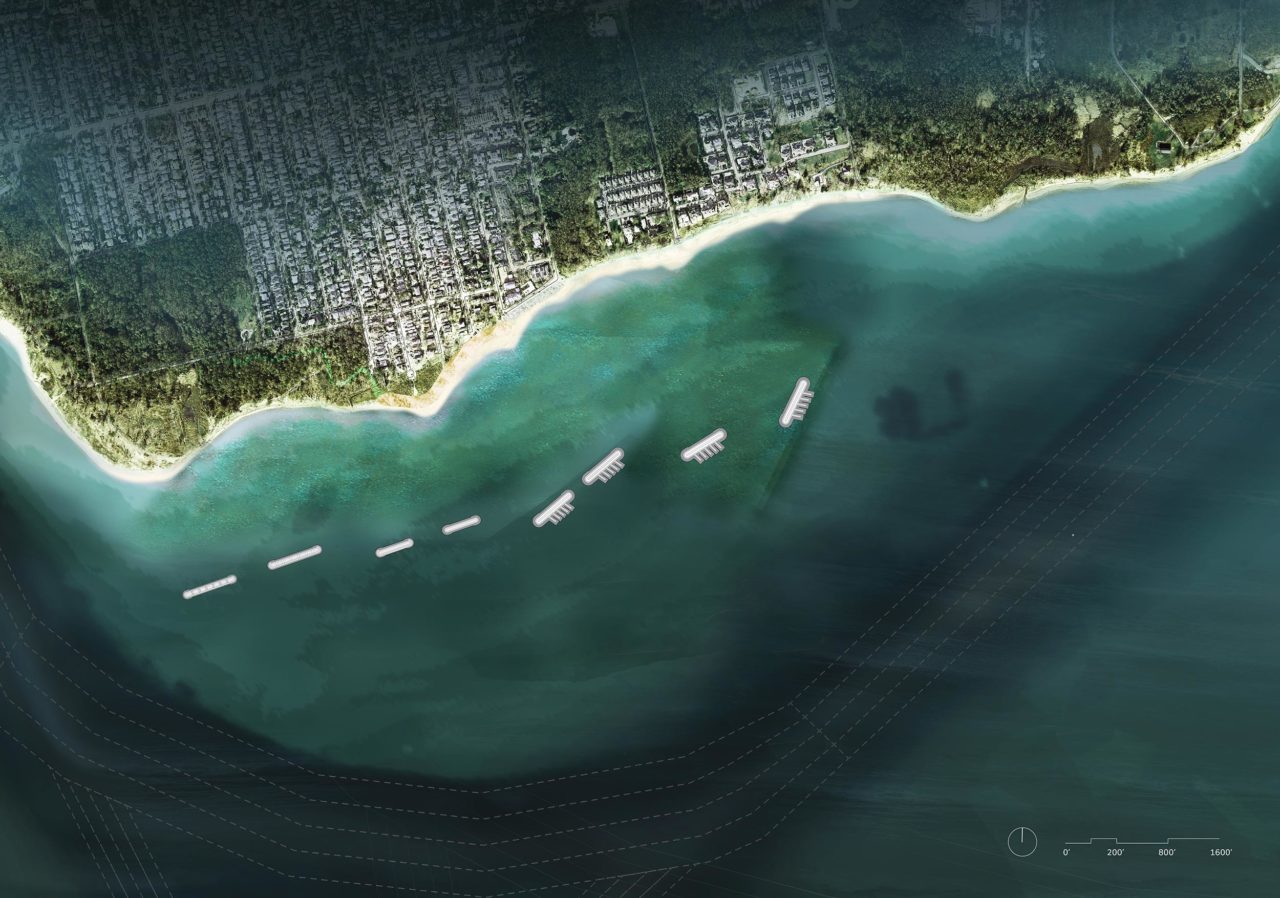

The work is already underway. Biologists are working on networking green roofs throughout all five boroughs. Ornithologists are teaming with architects to design safety measures for a vast bird ecosystem that helps sustain living rooftops. Academics are studying how trash collection systems can collect biodegradable waste to feed highly absorbent compost to parks. Landscape architects are modeling the kind of large-scale collaboration the future demands, partnering with multiple agencies in visionary projects like Living Breakwaters, which will install concrete barriers that provide marine habitat for oysters and fish while breaking waves before they reach shore.

COLLECTING GREEN ROOFS

There’s a 2015 photograph of biologist Dustin Partridge, Ph.D., smiling on the green rooftop of the Jacob Javits Center at the time he was completing his doctorate at Fordham University. Today, Partridge is the senior ecologist and green infrastructure lead at New York City Audubon, and managing director of the Green Roof Research Alliance (GRRA). He has seen birdlife grow and thrive on the Javits roof in ways he never imagined, to say nothing of the bats. “The bats are flying and actively forging,” said Partridge. “Whenever the moth numbers spike, the bat numbers spike as well, which is a neat kind of predator/prey relationship happening right now on a roof in New York City.”

With work spearhead by the Nature Conservancy, Partridge worked with colleagues from GRRA, and the Urban Systems Lab to map green roofs throughout the city. Less than 0.1% of the city’s more than 1 million rooftops are green, he said, which represents more than 40,000 acres of potential green space. He said that Local Laws 92 and 94 requirement of photovoltaic and green roofs on new buildings needn’t be a one-or-the-other choice; the two systems complement each other. Green roofs help keep the solar units cool, making them more efficient. However, more policy changes will be needed to make city-wide build-out at-tractive to property owners. “We’ve been working closely with legislators on the Green Roof Tax Abatement, which up until recent changes hasn’t been great,” he said. “It now offers $15 per square foot back to building owners in priority districts, significantly more than the $5.23 previously allowed.”

As sponges, citywide green roof expansion could create a significant reduction in water going into the sewer systems, but Partridge explained that most green rooftops are found mostly in Manhattan—even though the city has defined all priority districts for green roofs in the outer boroughs. “Priority districts were chosen based on the need for stormwater management and urban heat island reduction,” he said.

Partridge noted there is only an inch and a half of growth on the Javits, the bare minimum for a green rooftop. A Drexel University/Cooper Union study found that during a light rain event, the roof captured 96% of the water; during a medium-sized event, the roof captured 81% of the moisture; but during a heavy event, the roof captured just 27% of the rain. Over the course of a year, the building retains an average of 77% of the rain that hits it, preventing nearly 7 million gallons of runoff. Partridge said the study represents an important collaboration between architects, their client, and academia. GRRA hopes to foster more collaborations such as this.

“There’s new research coming out constantly, and it’s not always being directed into building this kind of infrastructure, and that problem goes both ways,” he said. “Academics don’t exactly know the real conditions on the ground, or on the roof in this case, and what it’s like to actually try to build these environments.”

Peter Olney, a senior associate at FXCollaborative, worked on the initial Javits renovations, which at the time was the nation’s second largest green roof. He said it wasn’t until the team built out the sixth acre of the 6.75-acre rooftop that the client approved and funded the monitoring systems that provided the data for the Drexel and Cooper Union teams to use in their study of the microclimate, energy performance, and stormwater runoff. However, researchers who didn’t require infrastructure, such as the scientists from the Audubon Society, were permitted onto the roof almost immediately.

Olney noted that the green roof turned out to be a cost-saving measure for the client, to say nothing of good public relations. Similarly, the bird-friendly ceramic frit on the mostly-glass façade also helps cut down on energy costs. Olney indicated that framing eco-friendly designs within a cost/benefit argument certainly helps convince wary clients. Christine Sheppard, Ph.D., director of the Glass Collision Program for the American Bird Conservancy, added that architects also get Pilot Credit 55 in their efforts toward LEED certification, which became permanent this past January (2022).

BUILDING FOR BIRDS

Sheppard said most birds have great acuity, except when it comes to glass. A row of decals that alert humans of a glass wall simply represents a set of obstacles for birds, who attempt to fly around the decals and into the glass. The ideal frit is large enough for birds to see with narrow spaces in between, she explained, so the birds don’t attempt to fly between the pattern. She’s also not a fan of ultraviolet coatings, which songbirds can see, but many other birds cannot. “There’s not much UV light very early in the morning when birds are very active, or on overcast days when the UV index is low,” she said, “but it’s much better than nothing and it seems to be the most acceptable to architects.”

She added that an amendment in 2020 of Local Law 15 to encourage the use of bird-friendly materials in new buildings represents a “huge shift.” Her idea of an ideal building is one that is surrounded by and/or incorporates bird habitat. “I think architects are so worried this will reduce their ability to be creative, and I don’t think that’s true at all, because you can make almost anything bird-friendly one way or another,” she said.

Sheppard also makes the financial argument, which she said is generally dismissed when it comes to birds. There are nearly 45 million birders in the U.S. spending more than $96 billion on bird watching. But that’s just the money spent by hobbyists, not the money saved by what the birds do for the environment. “Birds contribute billions more to our economy every year because they eat insects that can make you sick or can chew up your crops or forests,” she said. “When California forests burn to the ground, it’s the birds who bring seeds in so the habitat can regenerate. This is not just an issue for little old ladies in tennis shoes; birds are extremely important to people.”

THE CITY’S BIGGEST SPONGE

Tatiana V. Choulika, a principal at James Corner Field Operations, has been working for a decade on Freshkills Park, which is built atop 2,200 acres of landfill on Staten Island. The firm has been working on the site since 2001. She noted that birds have also been responsible for bringing more than a few seeds to that park. The big debate of the moment is whether to let the trees from those seeds set down roots on what is essentially a grassland green roof capping ever-shifting piles of garbage. “There are trees planted by birds; nature didn’t ask permission,” said Choulika. “Basically, a lot of people are worried that the roots will break through the cap and go down in the trash, but trees are not stupid: they’re stretching their roots toward the soil.”

Choulika said the park is ripe for research on endemic species that have found their way back to the former wetlands by way of Staten Island’s vast contiguous park system. The park, situated between the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge and Brookfield Park, aligns with the Staten Island Greenbelt, a 2,800-acre continuous nature corridor. She said that Freshkills is not unlike Dutch efforts at rewilding, specifically citing the wetland preserve Oostvaardersplassen, though that park is cut off from nature corridors that Freshkills benefits from.

According to Choulika, recent storms, such as Ida, have revealed the park to be “an immense sponge,” a site that absorbs rather than deters water. As the landfill was placed on wetlands, Choulika said the park is helping restore the site to its former role by creating a surge buffer. She added that wetlands are preferable to any attempt at trying to control water with a hard edge, which ultimately never works. “The edge is not the solution,” she said. “You need to give nature the space to breathe in and breathe out. You try to box nature in, it’s just not going to like it.”

TRANSFORMING TRASH

And while no one dumps trash in Freshkills any longer, it would be a perfect contender for composted waste, said Clare Miflin, founder of the Center for Zero Waste Design. When compost is added to soil, she explained, it can filter out urban stormwater pollutants by 60% to 95%. “Compost can hold five times its weight in water, while compacted soils, like soil found in much of the city, don’t hold any stormwater at all,” said Miflin.

Of course, collecting and processing organic waste would require a policy shift, which Miflin has been advocating for. She has researched the subject with the support of a Rockefeller Foundation grant through the Center for Architecture.

On a small scale, she said, Domino Park in Brooklyn serves as a good example of what could be done citywide. An average of 80 to 120 participating neighbors drop off about five to ten pounds of food scraps to the park, where the park staff manage the composting system. “Doing it small scale, run by the horticultural staff, will ensure that the compost produced is good quality and not contaminated,” she said. “A big part of what it’s about is making sure all city soils can be healthy sponges.”

She said that equipment can be added to most buildings that could turn kitchen scraps into fertilizer in just 24 hours. Elsewhere, David Prize-winner Domingo Morales has been focused on bringing composting to underserved communities via Compost Power, an education initiative. Regardless, whether compost comes from condos or housing projects, compost fertilizer could then be used in city parks and regional farms, said Miflin. But nothing will happen without political will. “It’s impossible to move forward without someone in the mayor’s office saying, ‘Hey, we want to facilitate this equipment; figure it out,’” she said.

POLITICAL WILL

Kate Orff, founding principal of the landscape architecture firm SCAPE, concurs that political will plays an integral part in building out green infrastructure, but architects and designers also have a role to play by building consensus around a vision. In 2006, when she was developing a visioning and mapping project for Gateway National Park, it required research and coordination among three counties, two states, the U.S. Army Corps, and the National Park Service. A cluster of New York City agencies, including the Parks Department and the Department of Environmental Protection, and all the local stakeholders, were also at the table. “I learned what goes into making change at a large scale,” she said. “I try to see the regulatory agencies not as the ‘enemy,’ but as partners who can potentially help us scale up, engage, and make change.”

Orff said that rather than attempting to ham-handedly push designs through agencies, it’s far more efficient to think of design as a tool that can help generate policy change and greater collaboration. “The main thing is you have to conceive of projects that break regulations to make any progress,” she said. “If we designed only within our regulatory context, we would just be doing vertical steel bulkhead walls.”

Her latest project will realize the installation of a series of submerged barriers including ecologically-enhanced concrete units intended to break waves before they hit the Tottenville neighborhood, which was significantly battered by Superstorm Sandy. Called Living Breakwaters, the project won the Rebuild by Design competition back in 2014. In Living Breakwaters, Orff has been able advance her designs through many years of outreach with local actors and government agencies. Another key was to go to the agencies early in the design process and get concept-level feedback. “It is not enough for designers to complain about how difficult it is to work with agencies,” she said. “I have zero tolerance for that. It’s on us to understand the processes and procedures.”

And while Orff said that government agencies are filled with talented professionals who have been on the job for years, administrations change, and what may be important for one administration may not be a priority for the next. To that end, when she met with Trump Administration officials about Living Breakwaters, she spoke less about rising sea levels and instead focused on engineering aspects of the project. “The big lesson here is that infrastructure and visionary projects of this kind don’t operate at the scale of one administration,” she said. “They really need to be able to transcend and evolve many years beyond any single administration.”

That said, she did point to the Obama Administration for initiating the Rebuild by Design effort. “It was an incredible experiment and a moment when the desire for innovation and infrastructure and the desire to do things differently was palpable and funded,” she said. “It was pretty radical at the time. It was coming down from the highest levels of government; they were looking at the future.” Orff said that since Sandy, the most difficult lesson of all is that no amount of money is going to save us. The future of architecture, she believes, needs not just a technological fix, it needs a philosophical fix. Over the last two decades, she said, the city went “from looking like a rock outcropping to a city of floor-to-ceiling glass expressions” that endanger birds. Architecture needs to shift from hero-based practices and take on less glamorous green efforts, like greening buildings and infrastructure that already exist.

“The idea of just retrofitting existing building fabric to be more energy efficient is probably one of the most profound tasks that architects could take on in the next decade,” she said. “It’s not the napkin sketch. It’s not the 3D swirling model. But it’s what needs to be done.”

—

Tom Stoelker is a senior staff writer at Fordham University. As a freelancer, he writes about and photographs the urban landscape for The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Wall Street Journal, The Architect’s Newspaper, and Landscape Architecture Magazine.