by: AIA New York

Susannah Drake, FAIA, Founding Principal of DLANDstudio Architecture + Landscape Architecture pllc, is at the forefront of interdisciplinary design and advocacy. Leadership of professional and community organizations, award-winning research-based practice, groundbreaking exhibitions, publications, and teaching typify her activist role in addressing climate change through design. Her large-scale planning work engages many disciplines and systems to create ecologically and socially progressive projects that are strategically conceived, well-crafted, and beautiful. Drake’s research has been at the forefront of innovation on urban ecological infrastructure. Her campus landscape design and large-scale urban infrastructure work received grant funding from the Graham Foundation, EPA, NEIWPCC, NYSDEC, and NYSCA. She lectures globally about resilient urban infrastructure, and has taught at Cooper Union, Harvard, Syracuse, Washington University, FIU, CCNY, and IIT. She is currently Associate Professor at CH Boulder ENVD.

“At a time when sea-level rise, flooding, drought, and fire are suggesting a need for movement away from vulnerable coasts and forests, COVID-19 may halt progress and lead to further sprawl and degradation of the landscape. A clear message is that urban open space is important for public health.”

– Susannah Drake, FAIA

The Jury of Fellows of the AIA elevated Drake to the College of Fellows in the second category of Fellowship, which recognizes architects who have made efforts “To advance the science and art of planning and building by advancing the standards of architectural education, training, and practice,” according to the organization’s definition.

Q: How and why did you choose to pursue architecture?

A: Fascination with the natural environment and open space is my passion. When I applied to Dartmouth College in 1982 the application asked: “What is the most pressing issue facing society?” In response, I wrote, “loss of our natural lands.” This may seem antithetical to architecture but a design-thinking course offered jointly between the Fine Arts and Engineering school helped me understand how I could use design skills to make a positive impact on the natural world. Urbanism was remote concept to me coming from a small town in Vermont. Five years at the Harvard Graduate School of Design pursuing MArch and MLA degrees and 25 years in New York City helped me understand the power of urbanism to protect nature.

Q: What are your favorite recent projects?

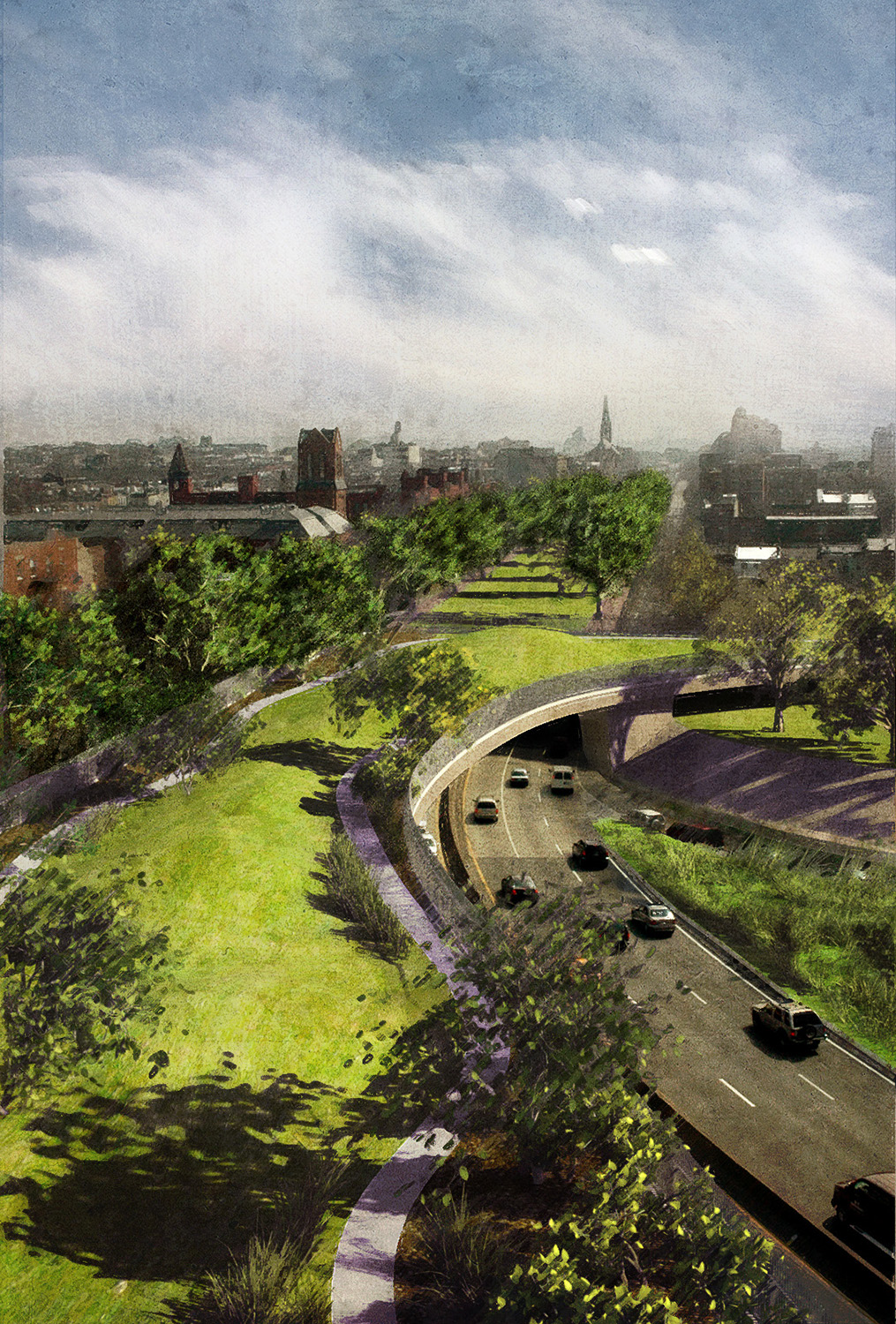

A: This question is like asking which is your favorite child. I have three kids and am proud of their collective accomplishments, with each contributing to the world in different ways. My projects are similar. Each one addresses particular problems facing society in an era of increasing climate change impacts. Invention is at the heart of my work on adapting infrastructure systems. Capping highway trenches along the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, developing policy and design recommendations for the 666 miles of space under elevated structures in New York City (Design Trust Under the Elevated), and creating the design guidelines for Miami Beach Historic Districts all reflect a need to change the relationship of infrastructure to people and the environment. Work on the Regional Plan Association 4th Regional Plan is a continuation of development of a suite of strategies relating to climate adaptation that began with the Gowanus Canal Sponge Park and MoMA Rising Currents (with ARO).

Projects included softened waterfront edges, expressive storm water management, increased permeability, and tiered strategies for managing the interface of salt and fresh water in cities. Recommendations for Coastal Urbanism in the 4th Regional Plan (with Rafi Segal) suggest migration to higher ground with a catalytic development proposal that migrates urban density away from vulnerable shorelines.

Q: How have recent advancements in technology impacted your work?

A: I am thankful that technology enables me to stay connected to my office and to collaborate more fluidly on projects around the world. When I founded the firm in 2005 in understood the need for remote access to the office. With three small kids of my own, I recognized that there are situations in life that can keep people from physically being in the office. Investment in flexibility proved useful as work at home orders were issued because of COVID-19. Beyond the crisis it also enables communication between offices in New York and Colorado.

A major component of our work involves communicating how infrastructure impacts urban environments. Many communities do not have the capacity to effectively broadcast public health impacts of the highways, post-industrial pollution, and climate vulnerabilities that plague their underserved urban communities. From analytical diagrams that express the problems to possible design, advocacy, and policy solutions, we use a range of techniques reliant on new and old-school technology to present a better future. Decoding the complexities of jurisdictions is a critical component of the work. With funding from the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and AIANY’s Arnold W. Brunner Grant, I developed an advanced modeling technique to map and communicate the dynamism of the tides, rain fall, and climate change impacts on the Gowanus Canal.

Q: What are your thoughts on architectural education today?

A: In August of 2019 I moved to Colorado to become Associate Professor in the ENVD Program at the University of Colorado Boulder. The interdisciplinary program is unique in that it includes planning, landscape architecture, architecture, and product design. In the tradition of the Bauhaus the students are exposed to design from a range of perspectives that touch issues of scale, ecology, mass production, craft, and beauty. Having taught in graduate and undergraduate programs across the United States including Harvard, Cooper Union, Wash U, Syracuse, FIU, and IIT, the interdisciplinary approach is refreshing. I believe we need to create design thinkers who can communicate effectively to leaders in business, policy, academia, and the press.

Q: What do you think are the biggest challenges, or opportunities, facing cities?

A: I am deeply concerned about the future of urbanism in the outfall of the global pandemic. At a time when sea-level rise, flooding, drought, and fire are suggesting a need for movement away from vulnerable coasts and forests, COVID-19 may halt progress and lead to further sprawl and degradation of the landscape. A clear message is that urban open space is important for public health. Frederick Law Olmsted’s experience in the sanitation corps during the Civil War informed his designs for Central Park, Boston’s Back Bay Fens and, in Brooklyn, Eastern Parkway and Prospect Park. Clean air and water, places to exercise, and places to interact with people were all critical components of his design work. Open space is not an extra amenity for the wealthy—in cities, it is a lifeline for all. With shelter in place orders, we have seen streets re-purposed as pedestrian and bikeways. Cities seem calmer and more friendly without the specter the car. With this mind, landscape should be considered critical infrastructure. The future of cities is green!

Editors’ Note: This feature is part of a series celebrating the members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) New York Chapter who are elevated each year to the AIA College of Fellows, an honor awarded to members who have made significant contributions to both the profession and society. Learn more about Fellowship here.