by: Anne Chen, AIA, NOMA, and Jesse Hirakawa, AIA, NOMA

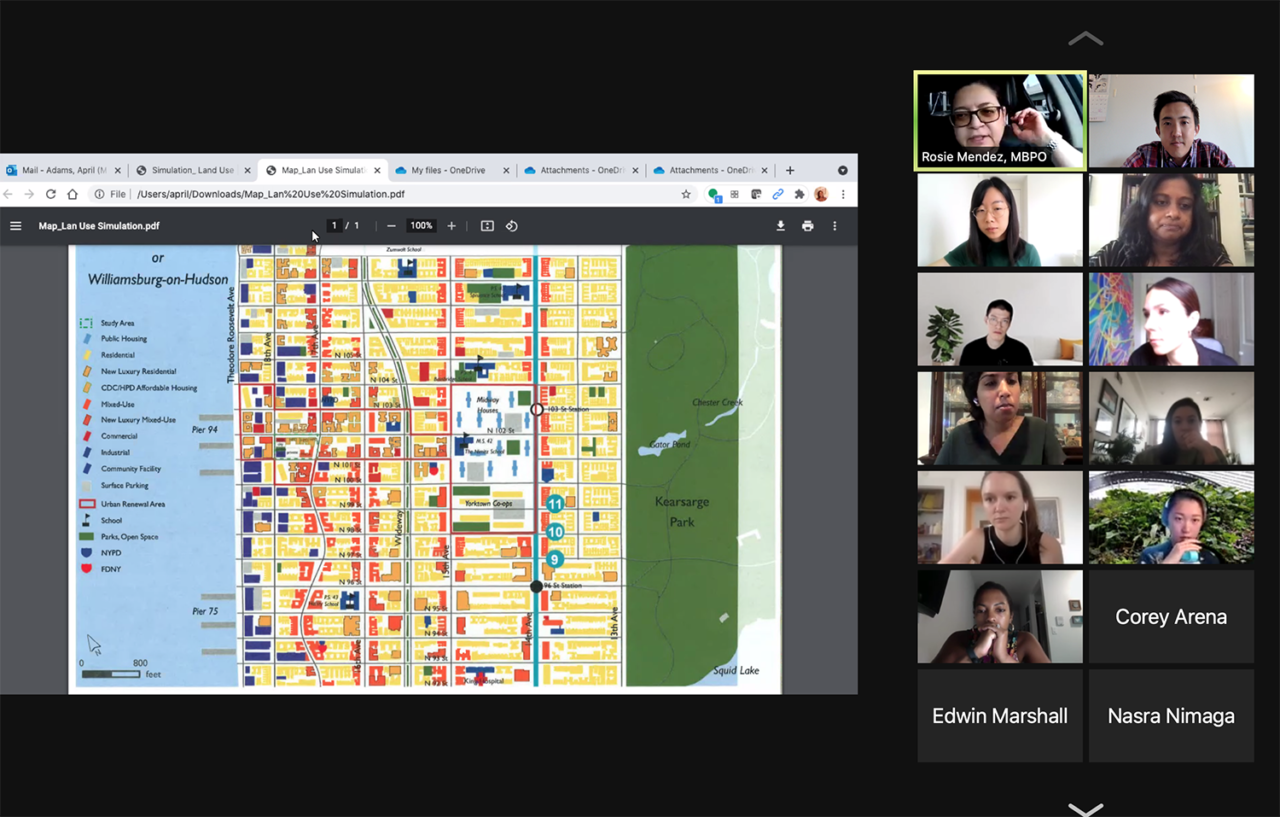

On Friday, August 27, 2021, the 2021 class of the AIANY Civic Leadership Program (CLP) convened for their third remote development session, organized by Anne Chen, AIA, NOMA, and Jesse Hirakawa, AIA, NOMA. The session, “Past, Present and Future of the Public Review Process,” dove into the history and the status quo of the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).

According to the NYC Department of City Planning (DCP), “The New York City Charter requires certain actions that are reviewed by the City Planning Commission to undergo a Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). ULURP is a standardized procedure whereby applications affecting the land use of the city would be publicly reviewed.”

ULURP consists of many participants and bodies of governments: DCP and the City Planning Commission (CPC), community boards, the borough presidents and the borough boards, the New York City Council, and the mayor. The procedure is set up to allow community members and local government officials to weigh in on land-use proposals. The process, which begins after the CPC approves the application, takes a maximum of 215 days, during which these different bodies have an opportunity to review the project .

New York City’s Statement of Needs for Fiscal Year 2020, an annual report required under Section 204 of the City Charter, reported that 25% of community boards noted that land use treads are a pressing issue in their community districts, and expressed the need for increased community input on large developments. Several community boards have issues with ULURP and have advocated for changes in how land is developed. However, before ULURP, community members had very few opportunities to comment on decisions that shaped their neighborhoods. While the system isn’t perfect, it is nonetheless an important way for people to make their voices heard. Attending public hearings and speaking with elected officials can make a difference in what gets built; public participation in ULURP has led to changes large and small and leads to better final projects.

Understanding the Status Quo

During the New York’s 2019 General Election, a ballot question was passed to amend ULURP, adding 30 more days community boards and borough presidents to review projects to the original 60-day community board review period. In addition, the amendment mandated DCP to inform community boards of project applications 30 days in advance of the start of ULURP. Supporters of the amendment stated that this was a good move towards greater transparency and providing more time for public review. Meanwhile, much of the opposition noted that what is needed isnt more time, but more effective methods for community input. Others opposed to the amendment stated that the additional review time simply created roadblocks to development.

Even more recently, the New York City Council introduced legislation to develop a new comprehensive planning framework, outlining goals for private- and public-sector design and construction. However, as noted by AIA New York, there are a few concerns regarding the development of a comprehensive plan. For one part, the plan would not be adopted until four years from now at the earliest, meaning architects would have to wait years to know what the city’s development targets are. Furthermore, while community districts would determine these targets and goals, these districts are outdated and have not been adjusted to demographic changes.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the city’s 59 community boards migrated to online platforms. Civic engagement soared as members of the public were able to participate in meetings from the comfort of their homes. As the state lifted the emergency order, community boards were once again subject to the state’s open meetings law, requiring physical public access to official gatherings. At the moment, however, Governor Hochul has suspended the Open Meetings law. While some argue that online participation has allowed more diverse members of the public to join, others contend that holding public meetings remotely ultimately silences individuals who do not have access to the necessary technology.

Points of View: Forms of Community Engagement

A history of redlining and a process that is overly technical has led to a lack of trust in the government’s ability to lead the public review process. Following conversations with public officials, individuals from the, private sector, and community board members, it is clear that there are aspects of the process that need to change. For one part, the makeup of community boards often fail to adequately represent community members.

In addition, the public must set goals for community engagement and figure out how to better share information so the public doesn’t feel like the decisions have already been made without them. Furthermore, community engagement can take many forms, and it is important to identify what form is appropriate at any given time.

The Future of Public Review Process

During the development session, the CLP participated in an interactive activity to further understand types of engagement, with categories ranging from non-participation (manipulation, therapy), to tokenism (information, consultation, placation), and citizen power (partnership, delegated power, citizen control). The group was dove into the topic by exploring four different criteria:

- Timeline and duration of engagement.

- The time set aside for community engagement is rarely sufficient. Advocate for a slower, more thoughtful process.

- Be conscious of how early to start and how late to stay in the process.

- Scale of engagement

- Whether a group is large or small, engage everyone equally and make sure everyone is part of the process.

- Deeply rooted engagement transforms the culture while transforming the space. Target those people who are directly affected to make a larger impact.

- Who to engage

- Ensure diversity of input across demographics.

- Incentivize community engagement by providing compensation such as metro cards or supporting childcare costs to ensure participation.

- Method of engagement

- Ensure equity and ease of access by bringing the information to the stakeholders

- Particularly in the post-pandemic context, it is important to explore whether digitization of processes fosters or hinders equity.

- Practice deep listening and learning

Thank you to all our guest speakers (in order of appearance):

Edwin Marshal, Senior Manager, NYC Department of City Planning

Rosaura Mendez, Director of Community Planning Boards, Manhattan Borough President’s Office

April Adams, Deputy Director of Community Affairs, Manhattan Borough President’s Office Adam Hartke, Chair of Land Use Committee, Manhattan Community Board 6

Elizabeth Canela, Project Manager, Totem Development

Matt Melody, LEED AP, Senior Associate, Curtis + Ginsberg Architects

Kristina Drury, Founder and Principal, TYTHE

Priyanka Jain, Co-founder and Principal, 3×3

Adriana Valdez Young, Director of Community, 3×3

Special thanks to:

Ifeoma Ebo, Founder & Director, Creative Urban Alchemy

Farzana Gandhi, Principal, Farzana Gandhi Design Studio

Delma Palma, Deputy Director of Architecture and Urban Planning, NYCHA

Teresa Gonzalez, Founder & Principal, DalyGonzalez

Jackie Turner, Principal, J. Turner Consulting

Kavitha Mathew, Special Projects Director, AIANY

Vera Voropaeva, CLP Advisor, AIANY