Revived by Beyer Blinder Belle (BBB), the landmark building houses exhibition space and hosts educational programs and community events as part of the South Street Seaport Museum—marking the culmination of a decades-long effort to honor the district’s maritime past while charting a new course for its future.

New York City owes its rise as a global center of commerce and culture to its origins as a seaport. For four centuries, the Port of New York has been central to the country’s growth, becoming the busiest harbor in the world by the end of the Civil War, fueling finance, manufacturing, and publishing, and establishing the city as a gateway for millions of immigrants. But by the middle of the 20th century, with waning maritime and commercial activity, the South Street Seaport district had fallen into decline and faced the prospect of demolition. Preservationists stepped in and, in 1967, established the South Street Seaport Museum, through which they purchased abandoned buildings and, together with the city, designated the area a historic district.

Commissioned in 1980 by the museum and the New York City Economic Development Corporation, BBB developed a master plan for the Seaport, establishing a framework for restoring the neighborhood while introducing new construction. Expanded with the guidance of Benjamin Thompson & Associates and the partnership of The Rouse Company, the plan focused on pedestrian-friendly streetscapes and identified key blocks for phased revitalization, guiding the district’s transformation into a dining, shopping, and cultural destination. In 1997, BBB reinvented four levels of a row of historic buildings as a new home for the museum, from which it could lead its preservation and education efforts.

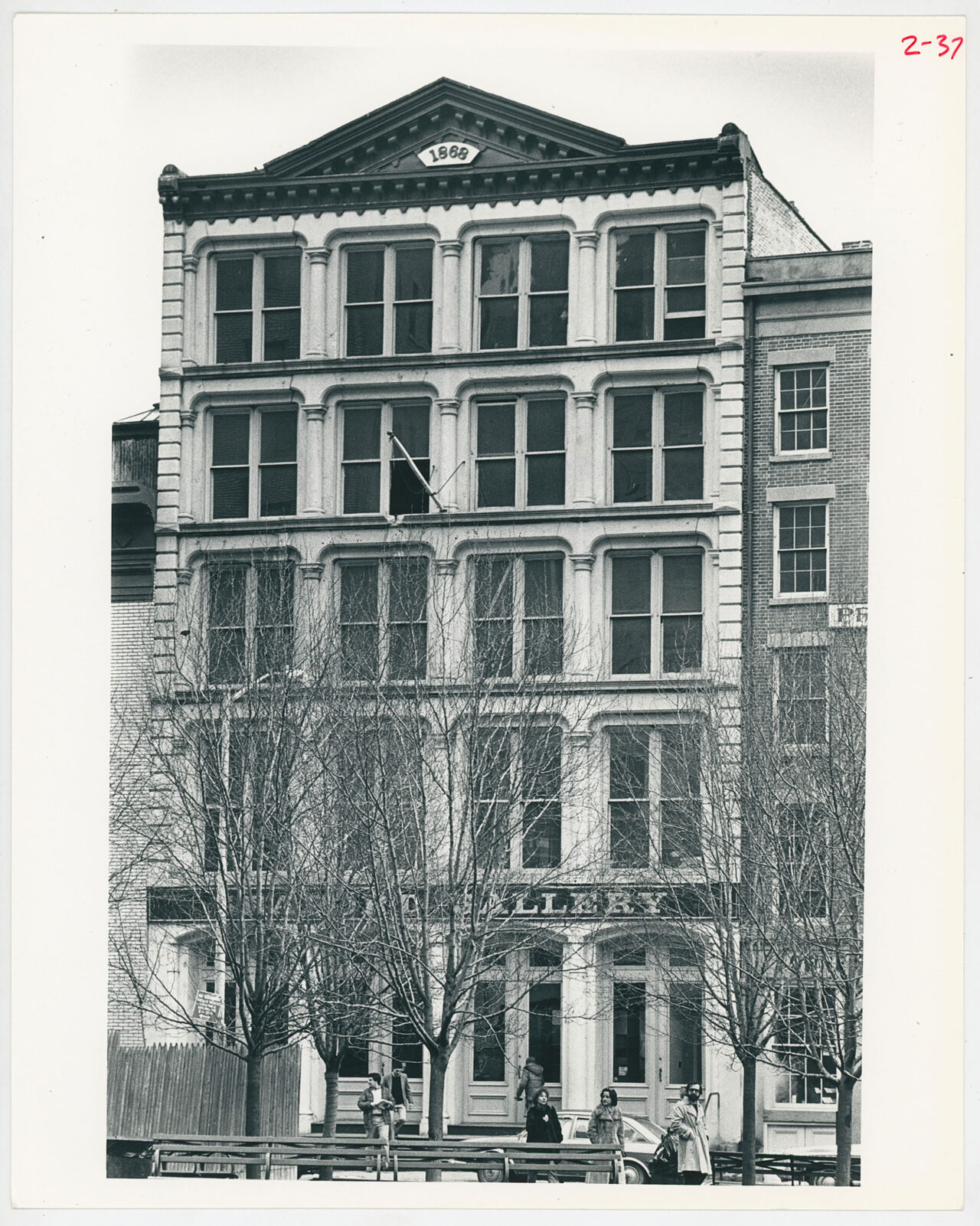

As the Seaport district evolved around it, the A.A. Thomson & Co. warehouse remained largely untouched. Designed by architect Stephen D. Hatch in 1868 for a metal importer, the five-story Italianate building features a cast-iron base and Tuckahoe marble-clad upper floors. Over time, it housed various businesses, including dye makers and office suppliers. In 1973, the City of New York leased the building to the Seaport Museum, which used it as a gallery, library, and collection storage area for more than 30 years. Following damage from Superstorm Sandy, the building became partly unusable.

Restoration efforts began with a 2016 grant from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation and the City of New York. Museum president and CEO Captain Jonathan Boulware recalls an early walk-through with the architects. BBB founding partner John Beyer “quickly saw the opportunity that the build-ing presented to the museum—and, indeed, to BBB, which was, in restoring Thomson, going to complete what they’d begun decades before. It was a perfect match,” recalls Boulware.

Throughout the design process, BBB’s team—led by partner Richard Southwick—approached the restoration with a light touch, upgrading the building to modern code and accessibility standards while preserving its character. The exterior was not within the scope of work, but it received a new entry platform and stair, minor repairs, and a paint refresh of the base. The interior, on the other hand, saw substantial upgrades.

The ground floor now features exhibition and event space equipped with state-of-the-art AV/IT, new partitions, and windows, all supported by a building-wide climate control system. To improve sightlines, BBB removed some of the closely spaced heavy timber columns, adding steel girders that are detailed in a style sympathetic to the original structure. Reinforcing and fireproofing were installed above the exposed joists, allowing the structure and heavy plank to remain visible overhead. Exposed ductwork, conduit, and services run along-side the joists, preserving a sense of layered history. Solid plank pine replaces warped wood flooring on the ground level, while sheet vinyl is used in the second- and third-floor galleries. At the rear, discreet structural cables stabilize the aging brickwork. Modern egress requirements prompted the addition of two fire stairs and the reversal of entrance door swings.

To safeguard against future storms, mechanical systems were relocated to the second floor, with underground utility lines encased in concrete. A new elevator incorporates the drive and controller components within the shaft, protecting it from potential water inundation. “We took the opportunity to not only restore the building,” says Southwick, “but to make it a model of resiliency.”

The inaugural exhibit, “Maritime City,” runs across the three exhibition floors. Marvel led the show’s concept and design, which features hundreds of objects displayed in a modular system of minimalist box-like oak vitrines of varying sizes. Some of these hang from the walls, and others sit on the floor atop casters and can be moved to higher ground in the event of a storm. The two top floors are flexible, available for future programming space, temporary exhibitions, or administrative use. The Thomson building has quickly become an important addition to the museum’s holdings, which include a 19th-century (still operating) printshop and five historic vessels, four of which are moored at Pier 16. “It adds a new center of gravity to the museum’s campus,” says Boulware, “and has already become a hub for new public programming.”

Throughout the project, BBB was careful not to scrub away the building’s industrial past. Ink-stained wood, graffiti, and mechanical remnants were preserved, offering a textured contrast to the clean, modern interventions. “We’ve learned not to over-restore,” says Southwick. This balance reflects the master plan’s long-standing goal: to preserve history while adapting for the present—a delicate task in a project spanning more than four decades. “It’s about retaining the patina and authenticity,” he adds, “and not losing that history while bringing the building into the 21st century.”

BETH BROOME (“Street Level”) is the former managing editor of Architectural Record and a writer based in Brooklyn.