by: AIA New York

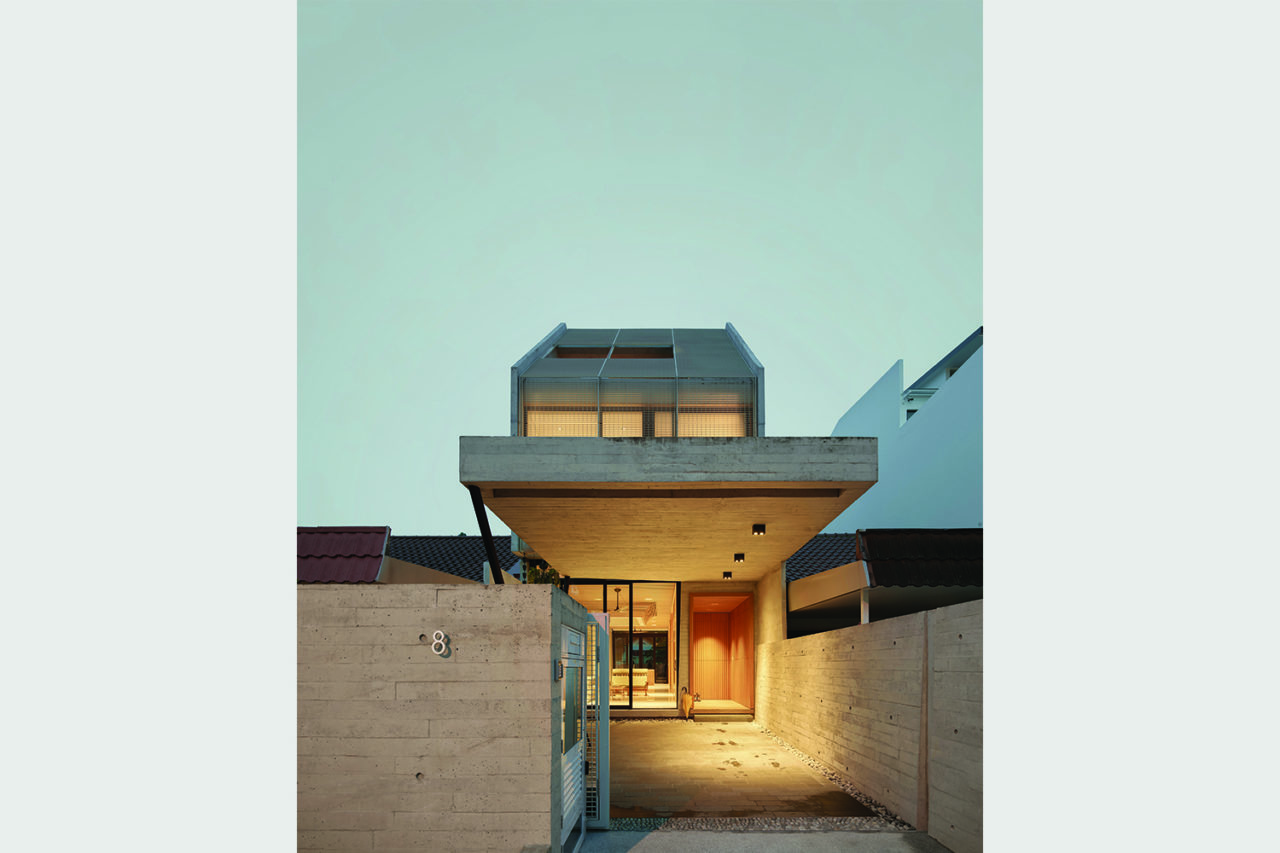

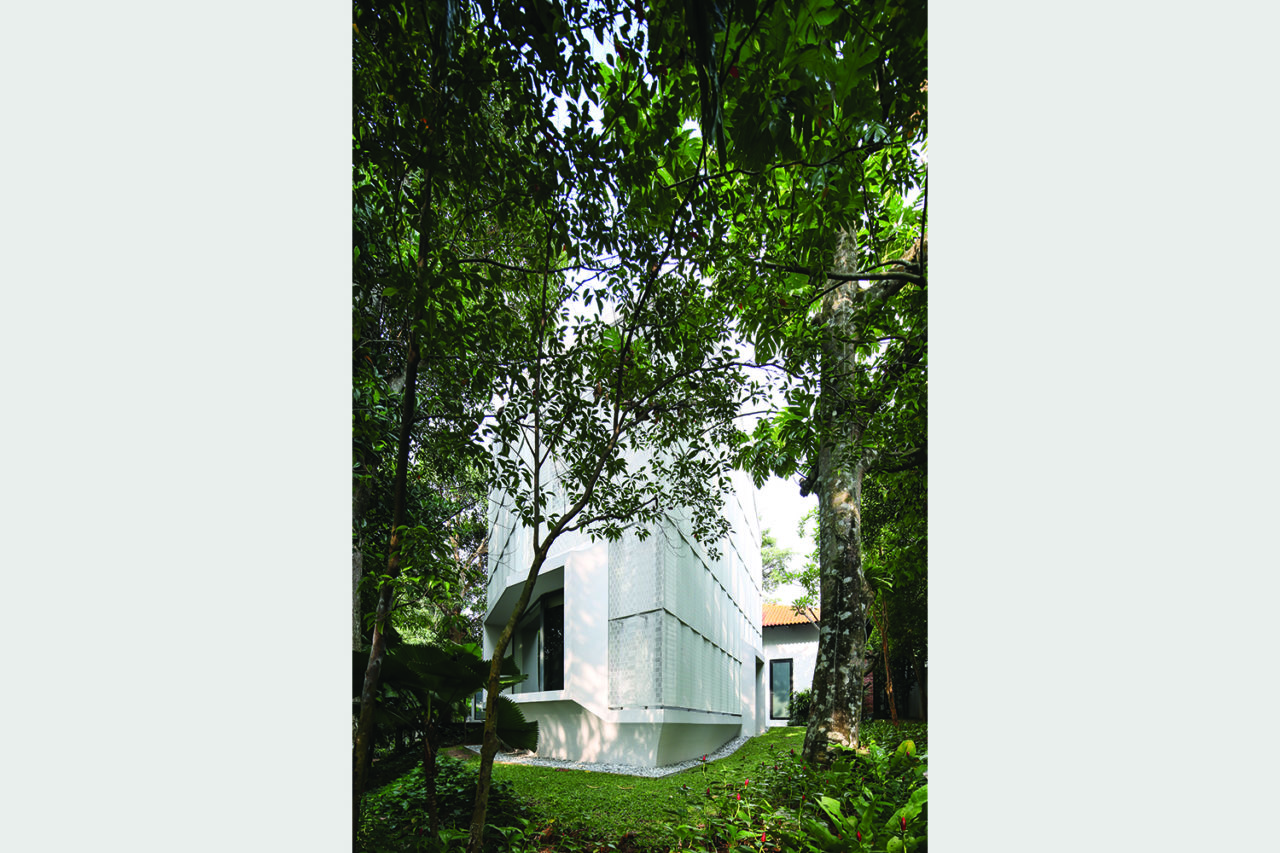

Erik L’Heureux, FAIA, LEED AP BD+C, is Design Director at Pencil Office, as well as Vice Dean, Special Projects at the School of Design and Environment at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He has developed a series of award-winning buildings that combine passive performance, pattern, and simplicity as a product of the hot-wet climate and the dense, urban equatorial context in Singapore, where he is located. A tenured professor at NUS, L’Heureux has been teaching and mentoring over 2000 students, locally and internationally for more than 18 years. He is leading the transformation of the School of Design and Environment at NUS with over 434,500 square feet of new and renovated facilities slated for completion by 2023. As BA Arch program director and Dean’s Chair Associate Professor, he teaches the new generation of architects to be committed to the complexities and potentials of architecture on the equator. L’Heureux sees the integration of design education, academic leadership, and creative practice as a hallmark of his impact, inspiring students, professionals, and the public to become more attuned to architecture fit for the equator and the warming world.

This year, the Jury of Fellows of the AIA elevated L’Heureux to its prestigious College of Fellows in the second category of Fellowship, which recognizes architects who have made efforts “To advance the science and art of planning and building by advancing the standards of architectural education, training, and practice,” according to the organization’s definition. While only three percent of the AIA’s membership is distinguished with Fellowship, L’Heureux’s investiture will be held at a future AIA Conference and AIANY’s next New Fellows Reception.

Q: What is influencing your work the most right now?

A: Two influences impact my work right now: The first is my continued interest in architecture that is positioned between the performative and poetic, while in calibration to the context of the hot and wet urban Equator where I practice. The second influence is concerning the agency of architecture in lowering embodied carbon in our buildings. For some years, I have been working on operational carbon reduction—on lowering carbon footprints in the use of architecture. The challenge now is reducing embodied carbon latent within architecture itself, to create delightful and exciting spaces for the larger public. My work with the adaptive reuse of the School of Design and Environment at National University of Singapore (NUS) buildings as super-low carbon, super-low energy projects speak of this ambition. Though not seemingly apparent today due to Asia’s recent building boom, adaptive reuse will soon be Asia’s future.

Q: What has been particularly challenging in your recent work?

A: Size. I am taking on larger and more complex projects that are public in their funding structure, larger teams in their makeup and more composite in the decision-making structures—all of which impact the design process. Working closely with team members of radically different cultural backgrounds and work practices adds to the complexity. Being nimble, honest, and open is the approach I bring to all my work and it seems to work for these larger projects as well. Size itself is also a challenge. A 56-story tower that I am working on in Kuala Lumpur is of this sizable volume that requires careful thinking about environmental impact, dimensions, proportionality, and the way architecture contributes to the city.

Q: What do you see as an architect’s role—and responsibility—within our culture?

A: The architect’s role today is to transform material resources and capital in the service of people and, increasingly, with more urgency towards the ecosystem of our climate and the wider planet. This requires a broad vision with strong leadership coupled with tremendous expertise rooted in the region where one practices. I strongly believe in the commitment to place-based practice, working in a location over many years to understand, navigate, and design contextually specific architecture. Architecture as a discipline is also a culture. Teaching and being involved in the shaping of the next generation of architects in one of my joys and passionate responsibilities.

Q: What are your thoughts on architectural education today?

EL: As an educator for many years, I dwell on a couple of ideas on architectural education today. First, we should have confidence in the discipline—that we train expertise for an analog world, even as we pull and utilize as much digital technology and material innovation in service of architectural and material knowledge. Our intelligence is in the crafting of our spatial environment today and imagining how it should be shaped for tomorrow. We should continue to reinforce this amazing and visionary skill set along with embedding the great responsibility of environmental stewardship in all our students.

Secondly, I firmly believe that the education of an architect needs to expand learning environments for students so that they become more entrepreneurial, empowering them with financial expertise, public domain capabilities, social capital skills, and manufacturing know-how to widen the opportunities where our graduates can lead. Students who are empowered to be deft, resilient, and agile will be the transformational leaders for our next generation.

Q: What are your greatest sources of inspiration?

A: My students and colleagues at the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore, where I serve as Vice Dean, challenge and inspire me with their dedication and perspiration, moving the conversations of architecture always forward in unexpected ways. And the hot and wet climate where I live likewise stimulates me every day. I was originally raised and educated in a temperate climate; the equatorial atmosphere has tremendous culture, aesthetic potential and latent knowledge influencing and impacting architecture not only on the Equator but for an expanding warming world.

Editors’ Note: This feature is part of a series celebrating the members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) New York Chapter who are elevated each year to the AIA College of Fellows, an honor awarded to members who have made significant contributions to both the profession and society. Learn more about Fellowship here.