-

October 16, 2023Toward an Architectural Education with an Awareness of Advocacy

![Toward an Architectural Education with an Awareness of Advocacy Event Photo 02]()

![Photo: Kuan-Ju Chen]() Photo: Kuan-Ju Chen

Photo: Kuan-Ju ChenArchitecture is a potent instrument for addressing societal, cultural, and environmental challenges. As practitioners, we can leverage design to tackle issues like climate change, inequality, and urbanization, crafting solutions that empower and uplift – and architects will need to do even more of this in the future.

On September 15, 2023, the Social Science and Architecture Committee hosted a panel titled Toward an Architectural Education with an Awareness of Advocacy. This gathering brought together architects, educators, and students to explore the pivotal role of advocacy in architectural education. Their insights shed light on the challenges faced by architectural education and the innovative approaches required to address them.

Committee member Sara Grant (Partner, MBB Architects) moderated, and our panelists were:

- Kelsey Jackson, M. Arch Candidate at Columbia GSAPP; Junior Designer, FXCollaborative

- Jieun Yang, Founding Principal, Habitat Workshop; Assistant Professor, CUNY New York City College of Technology; Leadership Group, Design Advocates

- Sanjive Vaidya, Chair of the Department of Architectural Technology, CUNY New York City College of Technology; Board of Directors, The Architectural League of New York

- Kristen Chin, Director of Community and Economic Development, Hester Street

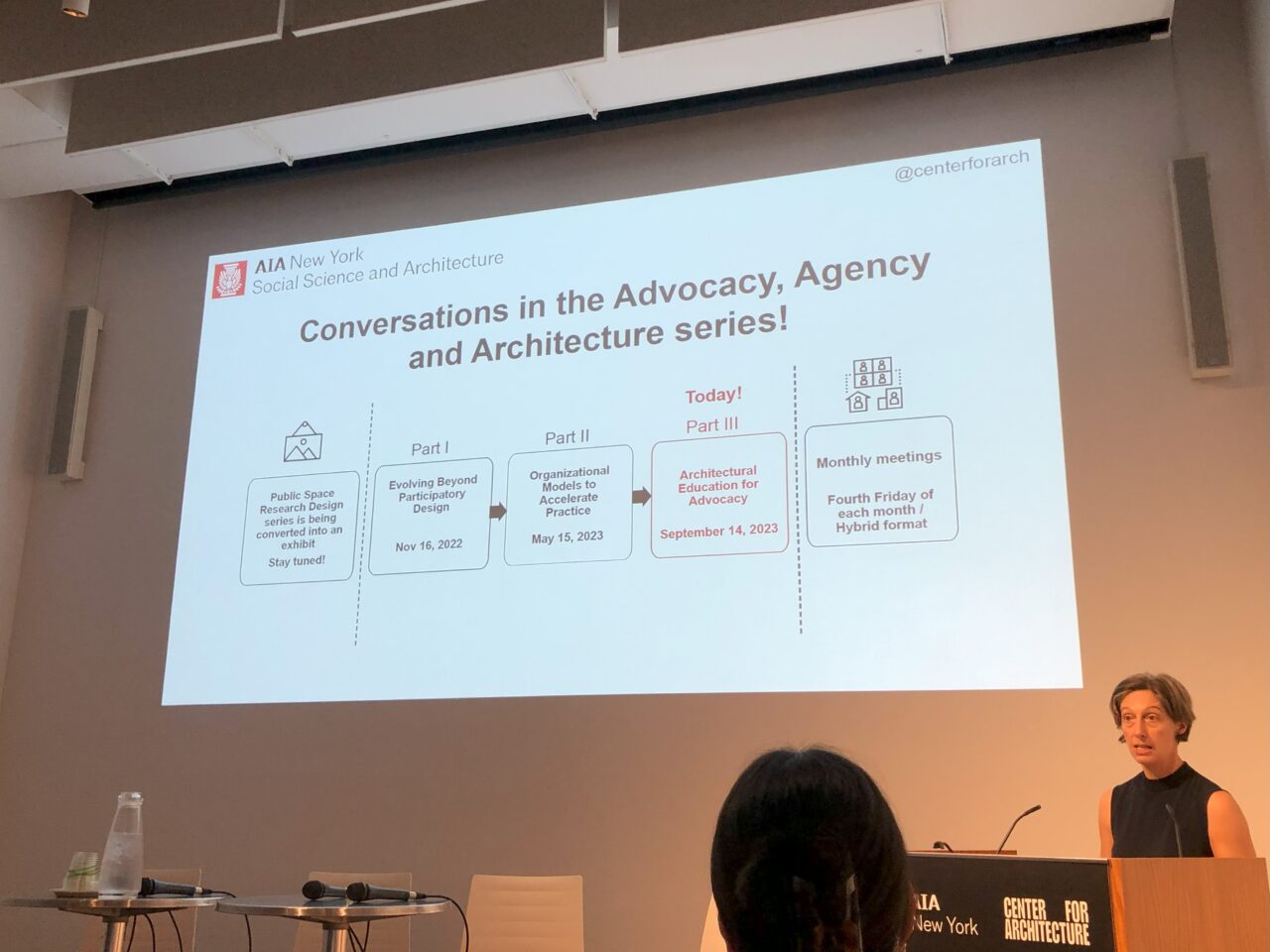

This panel was the third and final event of the Advocacy and Agency in Architecture series, the first two events of which looked at architects’ advocacy in their work impacting communities (“Evolving Beyond Participatory Design”), and architects advocating for themselves through non-traditional organizational models (“Organizational models – Acceleration in Practice”).

Architectural education has traditionally focused on technical skills and design principles, with the demands of accreditation failing to leave room for much else. However, the profession needs to adapt so that it – and its newest generation – are equipped to address the myriad of global climate and social crises that continue to emerge, impacting the built environment.

Kelsey, who is taking a year off from her architectural master’s program, had felt that her architectural studies were disconnected from both her individual interests as well as what was happening in the world. This was in stark contrast to the progressive primary school in Spain where she had worked, where students were encouraged to take control of their own learning. The focus was on nurturing agency and self-confidence, allowing students to set the agenda and teach classes, emphasizing the value of collective capacity.

The lessons learned from this pedagogy serve as a foundation for reimagining architectural education: encouraging students to learn through exploration and self-discovery, and ultimately preparing them for the dynamic and evolving field of architecture.

Jieun’s experience with Habitat Workshop and CUNY highlighted the importance of engaging students early in their architectural education. She discussed her pre-college program that introduces students to architecture through the use of simple prototyping materials and practical experiences such as taking time to understand and document their neighborhoods and working with local community organizations, using the city as a laboratory. For many students who believe “there’s nothing” in their neighborhoods, Jieun pushes them to look again: “There’s got to be something.”

In her eyes, architecture is a form of inviting relationships. Her approach not only provides a solid foundation for future architectural studies but also demonstrates to students a new way of seeing and thinking about the world around them and how they can have a tangible impact.

Sanjive, the architectural department chair at City Tech, highlighted the unique opportunity and responsibility of his program, given the extreme diversity of his students. The discussion raised questions about how to reframe architectural education, shifting from a focus on final products to celebrating the process, and how to make space amidst stringent accreditation requirements for needed changes – such as developing skills for critical inquiry, or ensuring the diversity of the student body is represented in the available coursework.

Recognizing that anyone coming into architecture has optimism and hope, Sanjive sees it as the responsibility of architectural programs to steward and cultivate that hope. Equipping students with the ability to ask meaningful questions and seek answers is an essential skill for tomorrow’s architects, as they are increasingly expected to be problem solvers who must help our society adapt to a changing world.

Kristen, representing Hester Street, highlighted the significance of community-centered design and exposing architecture students to this process, with the goal of architects being more aware of the communities they serve, particularly in underrepresented areas. Hester Street is engaging students in this practice through a new paid fellowship program called the Jim Diego Fellowship. She noted that there is a lack of design firms that truly represent the communities they work with.

Architects need to understand that their role goes beyond creating structures; they are catalysts for change and transformation. Inclusivity is key, ensuring that materials for engagement are understandable, accessible, and applicable to the communities they serve. Building relationships with community members is paramount to effective and ethical architectural practice.

As the architecture profession evolves, so too must architectural education. There is a need to teach students alternate modes of practice, focusing on programmatic longevity and adaptable design thinking, if architecture is to stay relevant in the future.

Architects must be prepared to engage with community members and empower them to have agency over their built environment – and that must start in students’ formal architectural education. Architecture is no longer just about designing beautiful structures; it is about empowering architects to shape a better world. We must cultivate the next generation of architects who can ask meaningful questions, build relationships with communities, and embrace an ever-changing landscape. It’s about training architects to understand the value of vulnerability, and recognize that building relationships is as important as constructing buildings.

In this vision of the future, architects lean into their role not just as designers but also as changemakers. It’s a future where architectural education is not limited by tradition and stifled by standards but is dynamic, inclusive, and responsive to the changes our society needs from architects. In this future, architects are better equipped to create a built environment that truly protects and serves the needs of all, and provides a place for all to thrive.

For those interested, please consider joining the conversation by:

- Attending our upcoming public events. Our next event series kicking off on November 2nd, will focus on the prevalence of forced labor in building materials – and what you can do about it. Details will be posted to AIANY’s Calendar prior to each event.

- Joining the AIANY Social Science and Architecture Committee Monthly committee meetings. They are open to the public and typically take place from 8:30am-10am on the fourth Friday of each month.

About the Author

Kate Ganim is a designer and strategist with a background in architecture. She is currently a co-chair for the AIANY Social Science + Architecture Committee and a Strategy Director at Artefact.

Social Science and Architecture

The Social Science and Architecture Committee was formed in January 2016 with the goal of bringing together professionals and students from architecture, social science, and other fields to discuss, collaborate, and facilitate programs for the community. The meeting offers a place to exchange ideas related to social science and architecture, address topics of interest to the attendees, and to plan AIA panels on related topics. The Committee meets monthly and is open to anyone who would like to attend. Meetings are held the fourth Friday of every month from 8:30–10:00 AM.