Info

-

Co Chairs

-

Namita Modi, AIAModi Architecture Design + fabrication (MAD+FAB)

-

Dennis Wedlick, FAIABarlisWedlick Architects

-

-

Special Projects

Upcoming Events

-

Tue, 5/14, 6:00pm

Topics

-

December 14, 2022

In a two-part AIANY Lunch & Learn: The Architecture of Goodwill on November 16, 2022, AIANY members heard from practitioners whose work serves people and communities with limited resources to commission professional design services. Moderator Duo Dickinson FAIA, NCARB, Principal, Duo Dickinson Architect, provided the following introduction:

“In this period of extreme change, the essential humanity of architecture is a constant. Architects Karin Patriquin AIA, Susan Odell AIA, and Pail Bailey AIA, join Duo Dickinson FAIA to describe how architecture and architects can find common purpose and fulfill their personal values and motivations by working in the Not For Profit sector. Rather than simply donated Pro Bono services these architects have used their skills to aid in the generation of projects that need construction to fulfill the needs of our most human of our cultural needs. A lively, interactive session conveys both the professional and personal opportunities this work affords for architects.”

Watch the program videos here:

-

March 11, 2022

For more than two hundred years the American Shakers have lived in simplicity and. . .unity in communal families. They liberated women, welcomed all races. . .perfected their quiet arts and crafts, worshipped God as Mother and Father, and expressed religious joy and love of each other by dancing and singing. (The Shakers and the World’s People by Flo Morse, University Press of New England, 1987)

On November 16, 2021, the AIANY Custom Residential Architects Network and the Shaker Museum of Chatham, New York co-hosted a panel discussion at the Center for Architecture on the early history of the Shakers and how the diversity of their communities may have impacted their cultural production and their architecture.

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, or the Shakers, as they are most commonly known, were a unique and self-governed faith organization that formed intentional communities for living, working, and praying throughout the United States during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Shakers are famous for their minimalist colonial architecture, furnishings, and objects, their striking music, poetry, and dance, as well as their numerous inventions in the fields of agriculture and home goods. For the most part, Shaker communities were farming and manufacturing settlements, where they produced highly-prized, internationally known, Shaker-branded agricultural and home goods—the prized Shaker seeds, brooms, baskets, boxes, chairs.

Dennis Wedlick, FAIA, Co-chair, AIANY CRAN, Principal Emeritus, BarlisWedlick Architects, explains: “Each household were given their own impressive dwelling where about sixty lived together, dormitory style, sisters divided from brothers, with female and male elder family members presiding over them. Each was given a house name, such as the North Family, the Center Family, the South Family, the Church Family.”

A gushing Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was allowed multiple visits with the Canterbury Church Family in 1842, provided a firsthand account:

September 27 was a fine day, I set forth on a walk. . .for the Shakers, distance three and half miles. . .They are in many ways. . .interesting, but at present have an. . .importance as an experiment in socialism. . .Moreover, this settlement is of a great value. . .as a model-farm. . .Here are improvements invented. . .which neighboring farmers see and copy. (Ralph Waldo Emerson in The Shakers and the World’s People by Flo Morse, University Press of New England, 1987)

Program participants at the Center for Architecture sought to explore the question: Did the diversity that was nurtured within these intentional communities drive these innovations? Guest speakers—designers, artists, historians, and curators—shared their experiences and considered the impact and legacy of the historic homes of the Shakers on their own work.

Jerry Grant, Director of Research at the Shaker Museum, with Maggie Taft, Preceptor at the University of Chicago, reflected on how architecture and product designs correlated with the Shakers’ utopian vision of home.

Ladies & Gentlemen Studio co-founders Jean Lee and Dylan Davis discussed “Furnishing Utopia,” a design workshop of their own making inspired by the legacy of the Shakers. While Lee and Davis were originally unfamiliar with the Shakers, the chose to learn about them by creating their own contemporary version of a Shaker community. They would gather with fellow designers of various backgrounds for three or four days at a time, living and working together in the countryside where the Shakers lived and worked, and imagining new utopian home designs inspired by whatever they came upon. And what they came upon was a connection with the Shakers’ longing for community:

When into union our spirits do run,

We find that our heaven on earth is begun.

– Shaker HymnThe program also featured a live conversation with choreographer Reggie Wilson of Fist and Heel Performance Group. Celebrated by The New York Times for his “sprawling movement pieces that fold history into the present,” Wilson’s “Power,” which was performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in January 2022, explores African American worship and Black Shakers dance. His presentation explored why these self-selected families of artisans and artists from diverse backgrounds—white, biracial, and black—continue to inspire the work of artists today.

Wedlick concludes: “As we go forward, we will continue to wonder: Did the diversity and inclusion, embodied in their home, drive the Shakers’ design and cultural innovations—the architecture, objects, narratives and dance, work that designers and artists around the world are stilled fascinated by? We hope this program will inspire and encourage others to visit Shaker historic sites and the Shaker Museum of Chatham, New York, to see for themselves.”

-

February 26, 2021

Zack Semke, Director and Curator of Programming, Passive House Accelerator and moderator of the committee’s recent Research Practice Series: High Performance Homebuilders program, discusses the importance of Passive House residential design.

When Dennis Wedlick invited me to moderate the AIANY Custom Residential Architects Network’s January 26 program Research Practice Series: High-Performance Homebuilders, I jumped at the chance. It was a privilege to introduce the basic principles of Passive House design to the audience, introduce four pioneering single-family projects, and moderate a lively discussion between project teams. As director of Passive House Accelerator, I welcomed the opportunity to connect with AIANY members around a topic near and dear to my heart: how to decarbonize the building sector.

Passive House Accelerator is an independent, open-source, online platform that shares Passive House information, lessons-learned, and best practices to help designers and builders accelerate the adoption of deep energy efficiency in new builds and retrofits. Our aspiration is to serve as a catalyst for zero-carbon building. We publish articles, produce the Passive House Podcast, and present a steady stream of online events, including Passive House Accelerator Construction Tech every Tuesday and the Global Passive House Happy Hour every Wednesday, which Dennis presented at on Wednesday, February 17.

We’ve been doing these online events for nearly 50 weeks now, ever since COVID-19 lockdowns began. Well over 3,000 people have attended at least one program during that time and a dedicated core community of a few hundred has coalesced. We are seeing firsthand that interest in Passive House design and construction is on the rise.

WHY PASSIVE HOUSE?

So, why Passive House? This photo shows the interior of a Passive House retrofit designed by Michael Ingui of Baxt Ingui Architects, one of our January 26 panelists and a founder of Passive House Accelerator. When Michael talks with clients about the reasons for doing Passive House design, he doesn’t necessarily mention the term “Passive House”. Instead, he’ll ask his clients if they want a better building. Do they want a building that’s sealed off from dust and bugs and unwanted moisture and odors? Do they want an indoor environment of clean, fresh air? Do they want warm walls and floors so that they can walk around in bare feet even in the dead of winter? Do they want a structure that is quiet and peaceful, creating a serene indoor sanctuary?

Only then does Michael discuss the sustainability benefits of Passive House and the role that Passive House design and construction can play in addressing climate change.

And make no mistake, Passive House has a big role to play in climate action. We all know that we need to get to zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or earlier, and that buildings make up at least 40% of the emissions problem. They are therefore also 40% of the solution. We need to decarbonize our buildings.

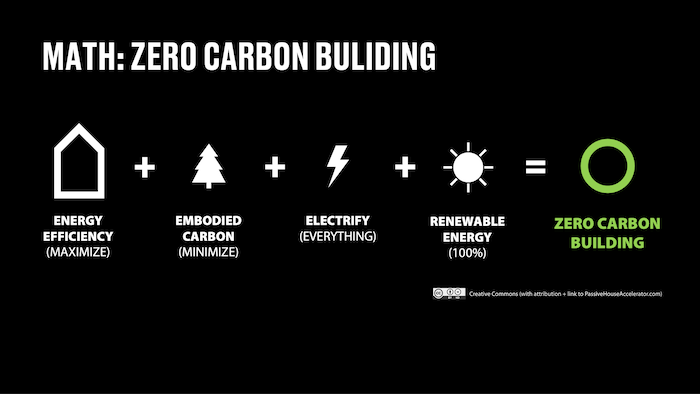

The math of zero-carbon building is fairly straight forward. First, we need to maximize energy efficiency. Then we need to minimize embodied carbon, electrify everything, and power it all with 100% renewable energy. There is no better way of reducing building energy consumption—of dramatically improving energy efficiency in a cost-effective and optimized way—than through Passive House design and construction. If you combine Passive House, low embodied carbon construction, electrification, and renewables, you can achieve zero-carbon building.

WHAT IS PASSIVE HOUSE?

The term “Passive House” is a bit of a misnomer in English; in the original German, “Passivhaus” means “passive building”. People are often surprised that Passive House design applies to all building types: schools, high-rise towers, institutional buildings, commercial spaces, and yes, single-family homes. Passive House buildings can also take on any style or shape, offering architects plenty of design flexibility. Passive House is about performance, not proscriptions.

Unlike checklist-based green building certifications like LEED, Passive House certification is focused on just three performance metrics based on good building science: heating and cooling demand (aka thermal energy demand intensity or TEDI), primary energy demand (aka energy use intensity or EUI), and air tightness.

In North America, there are two routes to Passive House certification for practitioners: the certification offer by the Passive House Institute (PHI) in Darmstadt, Germany and the certification offered by the Passive House Institute US (PHIUS) in Chicago. There are important differences between the two certifications (PHIUS has focused on modifying the three metrics based on the climate zone of any given project, for example), but both certifications share a focus on TEDI, EUI, and airtightness, and both employ a common suite of passive building design techniques to hit their ambitious performance targets.

FIVE PASSIVE HOUSE PRINCIPLES

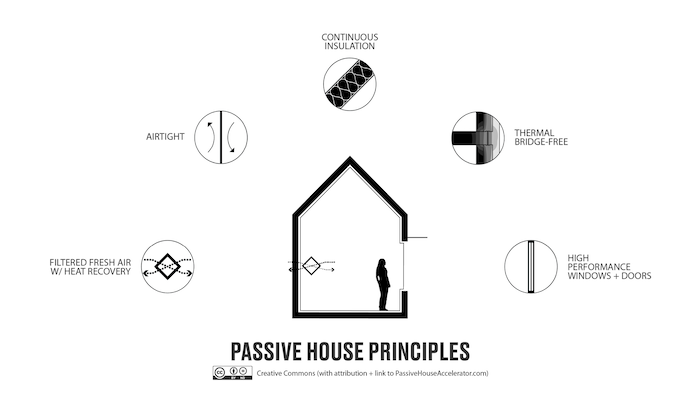

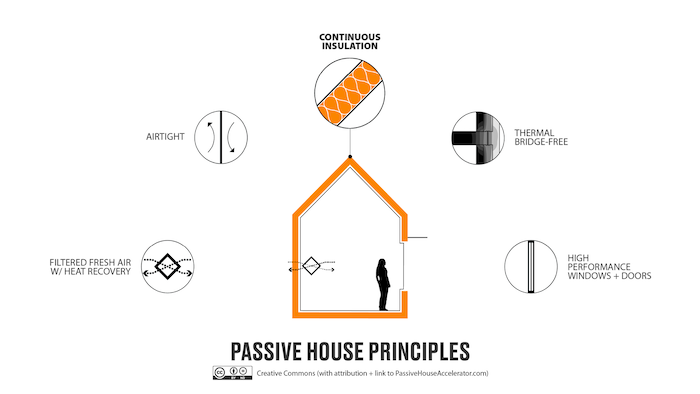

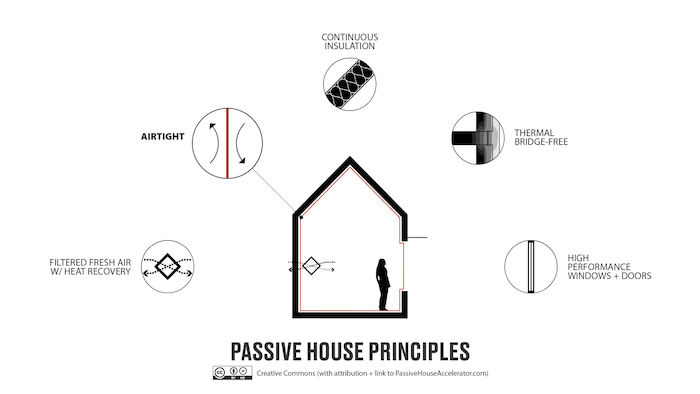

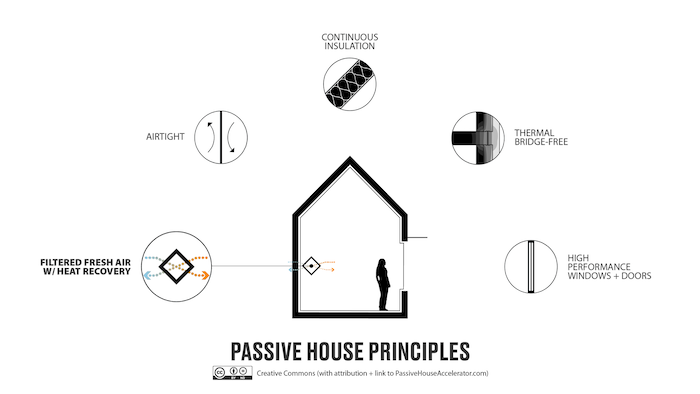

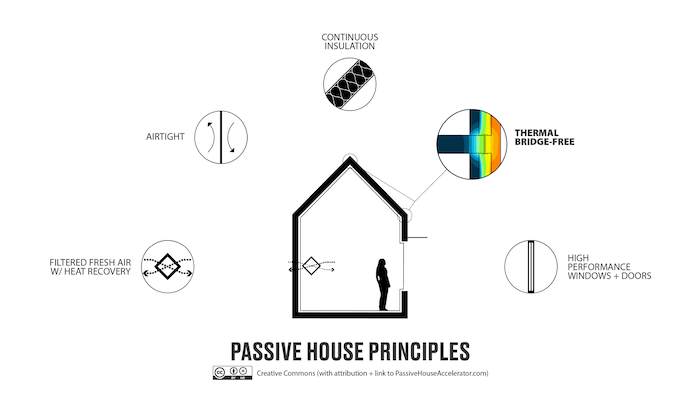

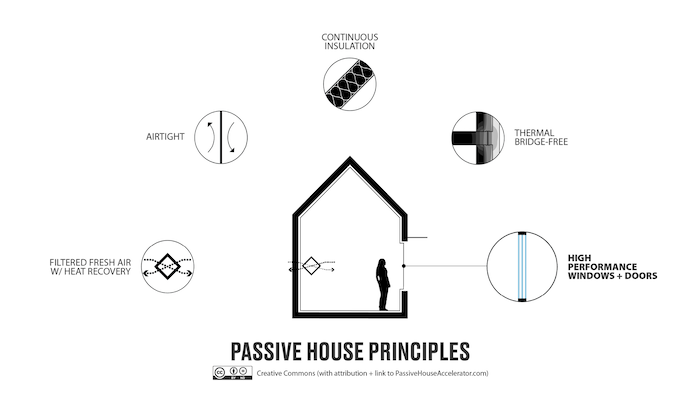

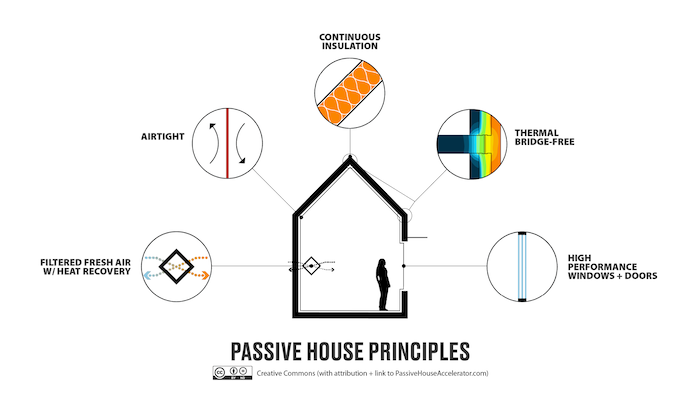

The classic way to explain Passive House design is through the “Five Passive House Principles”. (Note: the illustrations below are available to readers as part of a Creative Commons license, with attribution to Passive House Accelerator.)

The first principle is to create a continuous layer of insulation around the building, wrapping it in a cozy sweater to keep it warm during the winter and cool during the summer.

The second principle is to establish an uninterrupted air barrier around the building envelope, creating an unbroken “red line” of airtightness with tapes and membranes to seal off energy-sucking leaks (as well as the dust, bugs, and unwanted moisture that Michael discusses with his clients).

The third principle is to provide a constant supply of filtered, fresh air into the building with heat/energy recovery ventilation (H/ERV). H/ERV units transfer the heat energy from outgoing exhaust air into the incoming fresh air that is being taken into the building, all without the two airstreams ever mixing. The result is superior indoor air quality with almost no heat energy loss.

Fourth, we focus on thermal bridge-free design and construction. A common example of a thermal bridge is a concrete slab that extends from the interior to the exterior. Even the studs in an insulated exterior wall can become energy-sapping and moisture-inducing thermal bridges. Passive House designers create thermal breaks in building assemblies to avoid thermal bridges.

Fifth, we use high-performance windows and doors—typically triple glazed.

We bring all this together into a holistic solution using digital tools to optimize for both cost and performance.

As an architect, you don’t have to be a building physicist to harness the power of Passive House building science and Passive House design tools. If you are pursuing PHI certification, you’ll use the the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) as your digital tool. If you are pursuing PHIUS certification, you’ll use Wufi-Passive. In either case, you or someone on your team will also likely take advantage of some of the suite of digital tools that help with thermal and hygrothermal analysis of assemblies, like Therm, Flixo, and Wufi.

THE FOUR VIDEO STORIES

With that Passive House intro under your belt, I encourage you to take in the four compelling video stories presented at the January 26 event. The first video stars Michelle Tinner and James Moriarty of Sustainable Comfort discussing an affordable, multi-family Passive House development. The second features Jen and Brian Marsh and builder Jason Endres talking about a single-family Passive House project. The third features Buck Morehead and Kevin Dunathan discussing their single-family project that got paused midstream but was then rescued by a new contractor. The final story features Michael Ingui and Andrew Fishman as they describe their ambitious Passive House retrofit of an historic masonry structure in New York City. They are all inspiring stories, each with a unique take on the application of the five Passive House principles in the real world and the emerging power of architects to dramatically reduce building energy use, and therefore operational carbon emissions. Let’s take their lead!

-

September 18, 2020

Dear Colleagues,

One year ago, Namita Modi and I launched this knowledge committee with a panel discussion held at the Center for Architecture titled The Architect’s Challenge: Work/Family Balance. Who could ever imagine a time when the majority of New York City architects would be required to work from home to limit the spread of a deadly disease? The working conditions that Americans are enduring because of COVID-19 are so stressful that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have created a dedicated webpage to offer advice on how to recognize what stress looks like, take steps to build resilience, and know where to go if you need help. Learn more here.

One year ago, we invited architects and residential designers—Jane Frederick, Hayes Slade, James Slade, Sofia Zimmerman, Adam Zimmerman, Billie Tsein, and Tod Williams—who are design partners with their spouses to have a conversation regarding work/family balance. We were so pleased with the results and felt that there was an uplifting take-away that we should share with our colleagues during these trying times. Throughout their careers, all endured work crises and family crises—as all architects do. Yet, the entire conversation circled around the joy of architecture, the joy of dedicating their life to their vocation, and the joy of engaging their family—their spouses, their children, and parents—in their work. Perhaps, none would be able to be as single minded about their seemingly endless capacity to achieve a happy work/family balance if we held the conference today; but, the summary below, which was written soon after the panel discussion, explains how they felt back then and we felt it was worth sharing again.

Namita and I hope everyone gets the help they need to be as safe and sound as the possibly can be during these trying times.

Best Regards,

Dennis WedlickAIANY CRAN Review of the September 18, 2019 The Architect’s Challenge: Work/Family Balance,—a frank discussion with practitioners who co-own architecture firms with their spouses, written by Dennis Wedlick, co-chair of AIANY CRAN. (Written 9/25/2019 by Dennis Wedlick.)

Residential architects and their loved ones know that practices like ours require the business owners to work all hours of the day, all days of the week, and all weeks of the year. Spouses, children, parents, siblings, and friends all experience firsthand our round-the-clock workload: Builders reach out to us in the morning and late evening, while vendors, consultants, and colleagues keep us busy all during the day, and then clients have us going well into the night, on weekends, and even during holidays. Our collective experiences caring for our families and other loved ones while tending to the 24/7 needs of our businesses translates to a challenge that can threaten our abilities as both caregivers and practitioners. Those personal experiences—trying to give equally to our practices and our loved ones—inspired the idea for the panel discussion entitled “The Architect’s Challenge: Work/Family Balance.”

The Panelists: (Left to right) Hayes Slade, James Slade Sofia Zimmerman, Adam Zimmerman, Billie Tsein, and Tod Williams, and Jane Frederick.

Why hold a panel discussion on work/family balance specifically with practitioners who co-own their architecture firms with their spouses?

At AIANY events and AIA national conferences and symposiums, between sessions about best professional practices, the conversation among architects who own a small practice quickly turns from work to more personal matters—such as getting children into good schools, providing resources for aging parents, or helping a disabled friend get the support he/she needs. Once my co-chair Namita Modi and I decided to hold a panel discussion to address this challenge of work/family balance, we needed to determine who to invite to participate. Although all architects face work/family challenges, we decided to specifically host a conversation between architects who own practices with their spouses. Why? Two reasons: Firstly, all the panelists would be in a similar situation—an apples-to-apples comparison of one type of practitioner—one who co-owns a practice with their spouse—experiences work/family balance. Secondly, we assumed that architects who co-owned their practice with their spouse might find work/family balance doubly challenging when compared to architects whose business partner was not their spouse because both business owners would be dealing with the exact same work/family needs at the same time. We thought this particular set of panelists would highlight for the audience the work/family challenges that are unique to the practice of architecture.

Panel moderator Dr. Lois Oppenheim.

Through a jovial, thought-provoking conversation led by Dr. Oppenheim, the panelists offered a plethora of tried-and-true ideas for minimizing the challenges of balancing work and family needs.

As we all experienced on September 18, 2020 at the Center for Architecture, simply by answering questions about their work and their personal lives offered to them by Dr. Oppenheim—a skilled, probing, and engaging moderator—the panelists, Jane Frederick, Hayes Slade, James Slade, Sofia Zimmerman, Adam Zimmerman, Billie Tsein, and Tod Williams shared a frank presentation of the day-to-day story of their business and family life. To my surprise and delight, the panel discussion highlighted tried-and-true ideas for achieving work/family balance. They offered a plethora of positive experiences and thoughtful reflections about balancing work and with family needs that all can learn from. They did so jovially, humbly, without an agenda or aim. Their stories relay a career being immersed in their work 24/7, having their family fully integrated into their work lives, and knowing that working hard at architecture was a shared adventure of the whole family. Treasured stories about raising children, caring for aging parents, and working together—all the time—were told consistently as examples of why they love their chosen career paths.

AIANY CRAN Work/Family Balance at the Center for Architecture in Fall of 2019.

An unexpected takeaway: Comfortably blending your work life into your family life might be less stressful than trying to divorce the two.

When we listen to the conversation, we heard thoughts that may be unique for these panelists who co-own their practice with their spouses but may be useful takeaways for all architects. As an example, the panelists confirmed that their work life was entirely blended into their family life, and that was not only okay, but a good thing for all of them. Once it was explained, it was obvious to me how challenging it was for me to divorce my work life from my family life, particularly because residential architecture is a 24/7 business. Because my spouse was not my business partner when a call came in on the weekends, or I spent evenings thinking about a design problem, I would worry that my work was taking time away from being with family. And, when my business partner was called home for an unexpected family matter, he worried that his family was taking him away from the work that needed to be done. This is what leads to a feeling of imbalance that the married-to-their-partner panelists avoid because they share in everything: work and family. Therefore, one takeaway for me was: While challenging, maybe helping your family feel at home with your 24/7 work may be less stressful than trying to divorce them from your business, your passion. The panelists make it clear that architects cannot be their best possible selves—enjoying a happy family life while pursuing a successful business—if they feel pressured to compromise one for the other.

AIANY CRAN Work/Family Balance After Party at the Center for Architecture in Fall of 2019.

Conclusion: By sharing in conversations about work/family balance, we can learn from each other’s experiences. We encourage our fellow architects to continue these important discussions about our social well-being as a community of design professionals who are frequently under considerable stress and anxiety because of the challenges we face in our chosen profession.

We at AIANY CRAN are so grateful to all who participated, and we hope it will inspire future events to explore the work/family balance challenges that we all face.

-

September 11, 2020

The Residential Architecture Now: Mid-Hudson Valley webinar was hosted on September 2, 2020

Residential Architecture Now is a community-by-community survey produced by AIANY CRAN to help our colleagues, students, and residential design enthusiasts learn about the trends, inspirations, and resources related to a particular community of people within and near New York City. The results of our survey are presented with a series of panel discussion, which were originally to be held at the Center for Architecture until the pandemic of COVID-19 brought about a shift in our plans: We now present our findings using a webcast platform. That shift opened up the possibility of testing new ideas for sharing the knowledge and experience of our design colleagues.

For our exploration of residential architecture of the Mid-Hudson Valley, we asked four residential designers if they would be able to create short films about their work, and specifically we asked that they produce a conversation in the style of NPR Story-Corp. We were delighted that all four were excited to do so and produced their own interpretation of that request.

Below you will find the four short films included in the Res Arch Now: Mid-Hudson Valley survey accompanied by photographs of the projects featured and discussed during the conversations recorded. All four conversations describe the panelists’ experience designing modern homes in the most rural locations of this rural region of the Hudson Valley. All projects are located in the middle stretch of the Hudson Valley, north of Poughkeepsie and up to and including Hudson, New York. While this region is between a one and two hour drive north of Manhattan, it is primarily made up of thinly populated townships, villages and hamlets. Hudson is the only city included in the survey and its population is no more than 8,000 people. For the full webcast, which includes live introductions to the films and a live round table discussion that took place after the films were shown, please see the Res Arch Now, Mid-Hudson Valley video archive link, which will be posted soon.

The Stone House, built by Peggy Anderson LLC, located in Columbia County, NY

Builder: Peggy Anderson LLC. Architect: Steven Harris Architects. Photo: Cliff Goldthwaite.A conversation between Rural Intelligence Design Writer, Sherry Jo Williams and designer/builder, Peggy Anderson regarding her residential adaptive reuse of a nineteenth century tavern for her private residence, and a Hudson Valley home that her construction firm built recently in Columbia County, which was designed by Steven Harris Architects.

Cat Hill, home and fitness studio of Niki Nolan, located in the wooded surrounds of New Paltz, NY

Design Firm: Studio MM. Photo: Studio MM Architect.

A conversation between architect Marica McKeel and her client Niki Nolan regarding the design and construction of her newly constructed home and fitness studio overlooking the Shawangunk and Catskill Mountains.

Little Ghent Farm, the home, farm, and market of Mimi and Richard Beaven, located in Columbia County, NY

Design Firm: Pelone Bailey Architects. Photo: Adrian WM Jones

Mimi and Richard Beaven describe their experience designing and building their Little Ghent Farm—a home, farm, and market located just south of Hudson, NY— by answering questions presented to them by the architect, Neil Pelone of Pelone Bailey Architects.

The Accord House, home of Peter Reynolds, a certified Passive House built in the foothills of the Catskills

Design Firm: North River Architecture and Planning. Photo: Deborah Degraffenreid.

A conversation between design principal and Passive House consultant, Stephanie Bassler of North River Architecture and Planning, and her senior designer Peter Reynolds, describing their experience designing and building his certified Passive House home in Accord, NY.

Past Events

-

Thu, 2/1/24, 9:00am

-

Wed, 1/31/24, 9:00am

-

Thu, 12/7/23, 6:00pm

-

Mon, 11/13/23, 5:30pm

-

Sat, 9/30/23, 10:30am